The Icebreakers collective saw counselling informed by gay liberation politics as an equally valid and necessary way of fighting for LGBT+ emancipation alongside the more openly militant activism.

Gary de Vere and Colm Clifford, both founding members of SLGLF and the South London Gay Community Centre, saw counselling as part of the fight for gay liberation. They became involved in Icebreakers with a view to people coming out loud and proud as gay rather than merely a therapeutic 'adjusting' to their situation. It is worth looking in more detail at the group’s way of operating which distinguished it from the more cautious and distancing client-based approach of other counselling groups in the 1970s such as Friend, Kenric, the Beaumont Society and the Albany Trust.

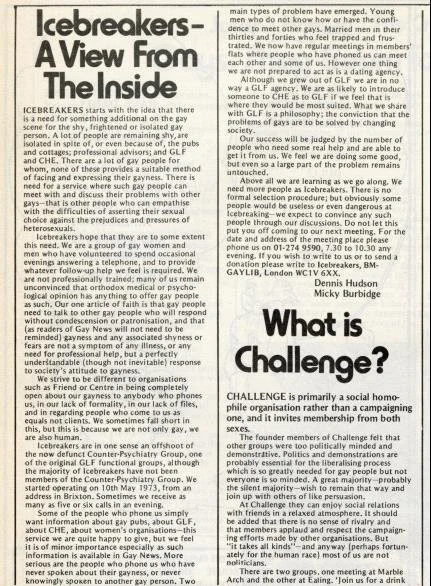

Poster advertising the help line

Icebreakers was an offshoot of the London Gay Liberation Front's Counter-Psychiatry group and began life in the summer of 1971. The group was established to answer the pressing need to talk to isolated LGBT+ people and to encourage them to 'come out' loud and proud. The original group met on alternate Sundays at Micky Burbidge's house in Ivor Street Camden Town. Before starting up the group consulted Anthony Machin the national Council for Civil Liberty's legal officer to check on its standing with the law. The main bone of contention was whether or not the group's activities could be construed as corrupting public morals or corrupting the minds and morals of the youth and minors.

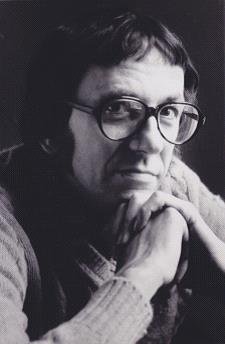

Bill Thornycroft in the 1970s

Bill Thornycroft (recently), who is now deceased

There were rigorous procedures for vetting Icebreaker volunteers. First there would be an interview with one man and one woman after which there would be a couple of 'sit ins' at the evening office sessions where more experienced Icebreakers dealt with telephone enquiries. Finally they would be invited to meet the whole group at the home of a volunteer for a chat and would be asked to leave the room while a decision was made about their suitability. With no hard and fast written rules about sexual relationships with contacts or introducing 'underage' males to each other these procedures ensured a secure way of selecting people who would not use their position to exploit others. No complaints were leveled against Icebreakers by contacts as a result of this careful and thorough screening of volunteers.

Icebreakers was a democratically run collective and accepted all genders and ages without discrimination including those deemed to be under the age of 21 which was the legal age of consent for gay men at the time. Roughly about three times as many men compared to women contacted the group. Trans people, pedophiles and those involved in SM relationships among others contacted the group for counselling.

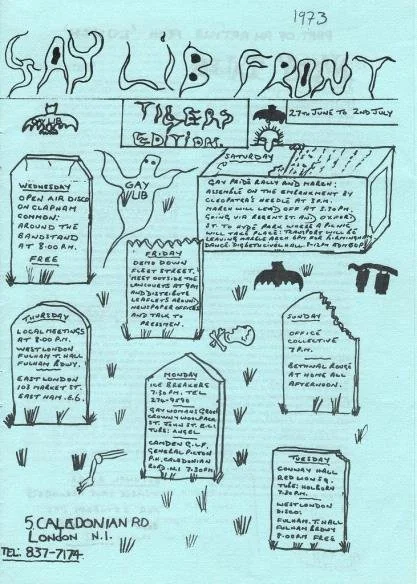

Gay Liberation Front events poster from 1973

The Icebreakers collective moved to Brixton in 1973 but originally fell foul of Roger Gleaves (aka the 'bent' bishop of Medway), an unscrupulous, predatory man who, unknown at the time to Icebreaker volunteers, was fully engaged in the sexual exploitation and abuse of boys. He ran a hostel in Brixton and picked up rent boys and runaways in Piccadilly and Euston station offering them a place to stay. In the 1970s hostels were not subject to detailed independent inspection or vetting procedures against those in charge as they are today.

A television documentary was being made at the time exposing his criminal activities. During the making of the documentary Billy Two Tone, a hostel resident, was murdered. Gleaves was never convicted of the murder but was eventually sent to prison in 1975 for four years for sexual offences against young boys and on release continued to reoffend setting up a bogus security firm to lure young men into his clutches. Icebreakers took up the offer of a room in his hostel but two volunteers, Micky Burbidge and Nettie Pollard, became suspicious of his behaviour and activities and acted swiftly on the offer of a new place to operate in a room above the squatted Peoples' News Service at 119 Railton Road almost opposite the South London Gay Community Centre at number 78.

Icebreakers was a revolutionary organisation that distinguished itself from other groups by unequivocally rejecting the approach of the helping professionals. The disallowing of the often patronising and sometimes wildly misconceived approach of social workers, doctors, psychiatrists and counsellors was born out of the solid belief, gleaned from gay liberation ideas and practices, that it was society that needed to change rather than the individual in order to end LGBT+ oppression.

Individual self-esteem rather than a guilt-ridden self-loathing was encouraged within the context of challenging external pressures of widespread social disapproval and political oppression. The objective was to ease entry into a wider world for those who had been battered and bruised by isolation, loneliness and low self-esteem. The most important element in this was to encourage a one to one relationship through contact by telephone and in person. Gradually those who had been contacted would be encouraged to come along to 'tea parties‘ every Sunday afternoon and for women every Friday evening which were held at the homes of volunteers. The object was to meet other LGBT+ people who were just coming to terms with their gender and sexual identity and the collective's volunteers who were proudly and confidently gay. Gary de Vere held monthly meetings at his home for all Icebreakers and potential volunteers. Some contacts eventually became Icebreakers.

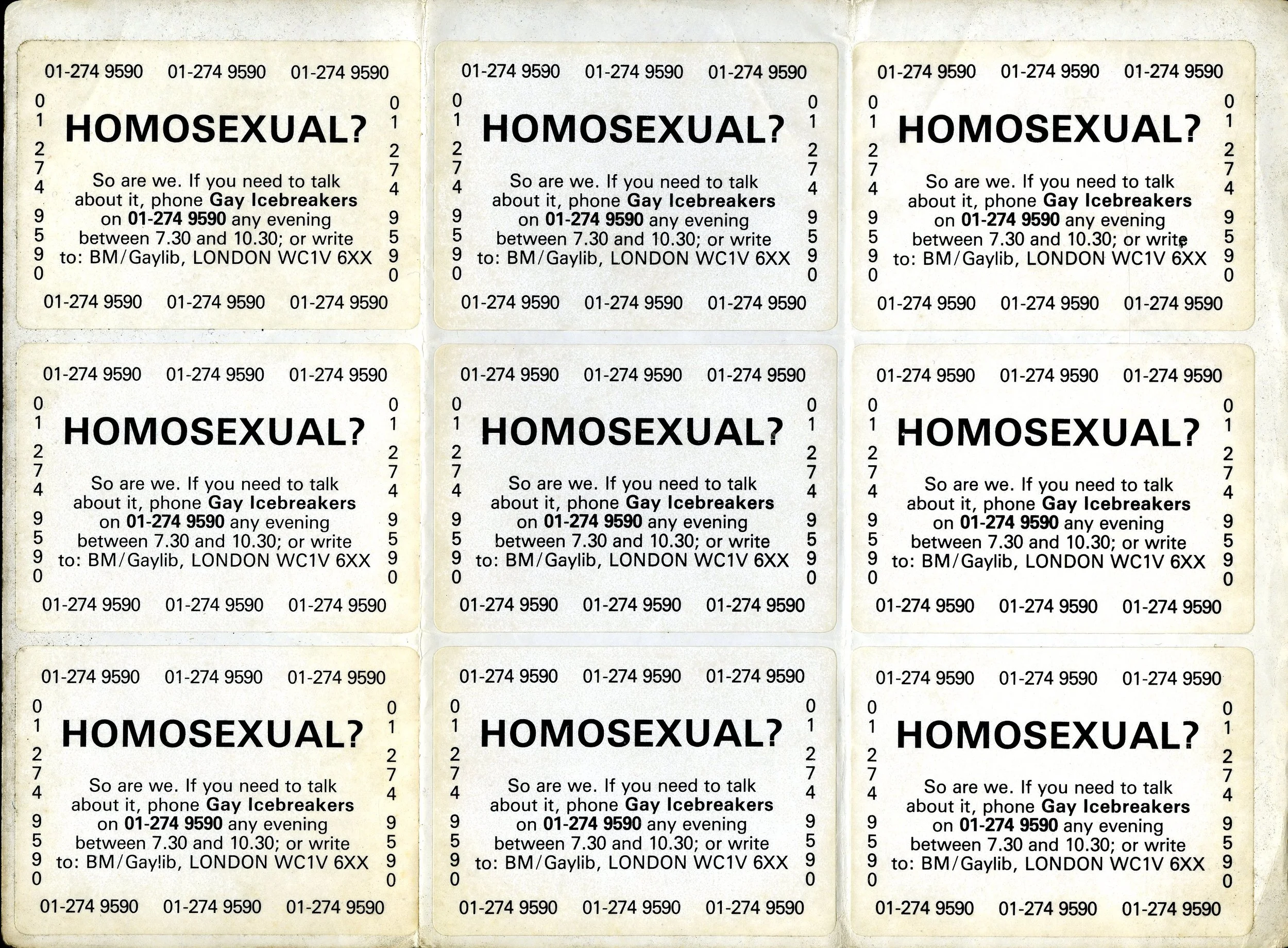

In the days before the internet and mobile phones Icebreakers advertised itself via gay newspapers and magazines. One entry on the advice page of 'Woman's Own' led to an inundation of letters from gay men!! Stickers were also produced to be put up on tube trains, bus shelters and wherever people gathered in large numbers though Nettie Pollard even remembers putting some up at remote villages in the Highlands of Scotland.

It is interesting to compare the different sides of gay liberation politics. On the one hand there were the openly gay activists caught up in the cut and thrust of building a gay community presence in an essentially hostile environment. On the other there were those who devoted their time to the less dramatic and often unnoticed but equally valuable task of assisting closeted and fearful gay people to overcome silenced agony or quiet desperation. But in Icebreakers case this was not simply a question of passive referral to other agencies to deal with specific problems or a quick fix job with swift abandonment to the tender mercies of a limited gay scene. There was a definite commitment to building a new awareness and a new set of possibilities in social and political terms for gay people. Volunteers where, in the main, political activists.

Gay Icebreakers badge which was worn to advertise the helpline

The chief difference in approach to counselling gay people ( ‘counselling’ was a term the Icebreakers Collective was ambivalent about using) lay mainly in their challenge to the notion of expertise. Claimed by professional social workers, psychiatrists and counsellors and adopted in the less stridently ‘detached’ approach of the other organizations mentioned Icebreakers abandoned the aura of the highly trained professional educated in the problems of others. Abandoning the condescending attitudes towards supplicant ‘clients’ Icebreakers declared themselves as an organisation that was run by gay people for gay people with no interest in adopting the disinterested, objective stance of other non-gay groups. The emphasis was very much on community self-help and self-organisation.

This was also reflected in the administration of business and how the group was structured. There was a resolute determination to maintain a collectivist, democratic spirit with regular meetings of volunteers to determine its policies and direction. Unlike other groups that hurried themselves into a rush for a more official status by the need to impress various funding bodies the scramble to elect a chairman, secretary, treasurer and so on was rejected.

With a deliberate policy of refusing public funding or private charitable donations and an equal determination to remain a small and accessible group rather than to grow into a bigger and increasingly remote bureaucratic body, Icebreaker's independence remained in tact. This caused considerable problems in terms of revenue with the need to set up occasional 'benefits' and charging contacts a pound a month to meet the costs of renting a room, running a telephone service and various other overheads. Needless to say the group relied completely on voluntary labour of those committed to a gay liberation ethos. The Icebreakers disco at the Prince Albert public house on Wharfdale Road, Kings Cross (now Central Station) was one of the most popular venues with regular attendance by devotees and a warm and friendly ambience for newcomers. It proved to be an excellent place not just to socialise but also to sexualize with many liaisons coming to fruition. The landlord and bar staff were friendly but that position changed later when the landlord barred a gay man for his ‘punk’ appearance. Apparently the landlord had trouble from some punks prior to the banning and wished to pre-empt any further problems. This was seen as a grossly unjust measure forcing the Icebreakers disco to move out and use a new venue at the Hemingford Arms in Islington.

Micky Burbidge the founder of Icebreakers also now deceased. The appalling treatment of gay people by the psychiatric establishment, especially using aversion therapy to 'cure' homosexuality, prompted him to set up the group. The struggle goes on now that aversion therapy has been re-branded as so-called conversion therapy by religious groups and some in the psychotherapy profession.

Micky Burbidge 1990’s

In the first eighteen months of its existence Icebreakers enjoyed considerable success. There were only a few letters sent to their ‘Troubled Waters’ column in the ‘homosexual’ newspaper Gay News. At this point in time people were still reluctant to openly declare their gay identity and preferred the anonymity and immediacy of Icebreakers nightly telephone line. Almost 2,500 calls had been received during this period. Clearly Icebreakers had grown in importance and in a letter dated 25 November 1974, Gary de Vere, a prime mover in the squatting of the South London Gay Community Centre, outlined the necessity of lobbying Lambeth Council to release Icebreakers from payment of rates and emphasised the fact that asking people to dip into their own pockets to fund Icebreakers was not sufficient to cover costs. Clearly this was a break with the refusal to be funded by other organisations and a threat to independence but it was also seen as a small move towards being recognised by a public body.

A letter to Mr. Hughes-Narborough, the Valuation Officer, is interesting in revealing how much ducking and weaving had to be entered into to get the local authorities to waive the payment of a paltry sum of money. Gone are the proud declarations of Gay Liberation. Icebreakers described themselves as a "Samaritan-type help Organisation for homosexuals“ providing a valuable social service. There are hints at a certain amount of annoyance in the letter. Why pay rates (community charge) for a small room without facilities? There was one electric heater but the toilet had to be shared with other occupants in the building and so on. Not only that but to refuse rates exemption would mean bureaucratic time-consuming negotiations with Lambeth Council for funding.

But did this ducking and weaving really matter? The political overview then was that LGBT+ people should be as equally entitled to public funding as all the other straight groups. It became a question of equality of recognition which meant any means could be used to secure sufficient revenue to survive. Besides, didn't Icebreakers simply engage in the business of embroidering their application for exemption as any other group would do in similar circumstances?

Who actually contacted Icebreakers and for what purpose? The channels of communication consisted of articles appearing in Gay News and Lunch as well as the phone line and British Monomark address. Stickers were also plastered on public outlets such as tube trains, buses and telephone kiosks. Some callers preferred not to talk too long on the phone through shyness or other reservations and requested the address to allow a more complete contact by Letter. Here are a few examples of letters received by Icebreakers to give some indication of who contacted the group and for what purpose. All the names have been anonymised.

PB of Wolverhampton, in a letter dated July 1973? Stated clearly his dissatisfaction with the FRIEND organisation in Birmingham. He objected strongly to its insistence on acceptance by the establishment (social services) above providing real help for those who needed it most, particularly those who did not fit in with generally accepted norms of social respectability or were below the age of consent. In response to Icebreakers advertisement for more information about TV/TSs groups he offered to put them in touch with someone who ran a similar group in the Midlands.

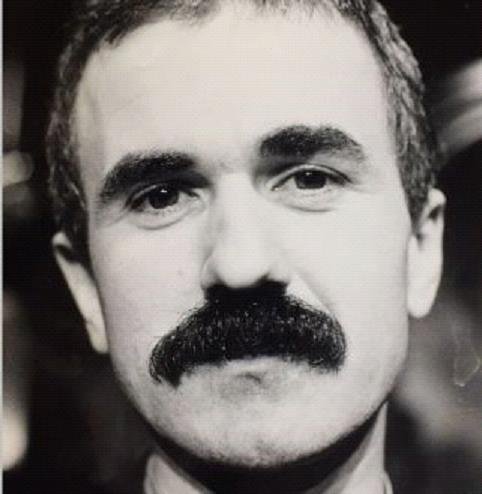

Colm Clifford (right) in 1970s

Colm Clifford, late 1980’s, now deceased

SP of Fulham, on 4 August 1973, was middle-aged and had great difficulty in meeting other gay people through lack of confidence and fear of rejection. He was invited to an Icebreakers ‘tea party’ providing the opportunity to meet other gay people in the relaxed and congenial surroundings of a volunteer's home.

RM from Cardiff, asked on the 25 August 1973, if it would be possible to work with Icebreakers to start a regular newsletter for transvestites with a view to gaining a wide readership nationwide. Could Icebreakers get interested people to write to him?

Gary de Vere, on behalf of Icebreakers, was able to inform MD from London on 7 September 1973 that a group for TVs had been set up at the home of SG, also in London.

MD gave a brief description of himself as 29, of average height and build, married with a young daughter, but he had been a TV for as long as he could remember. His wife knew about it but was horrified and he was not allowed to dress up at home. He got little joy from professional call-girls and did not have the cash to indulge his character. He described himself as bisexual because he loved to have sex with girls but also loved to have sex with TVs whether dressed up or not. His "ultimate" scene was with another TV when fully dressed up. His taste in clothes was 'tartish" and he had been informed that this was just a phase one goes through. He needed to know if there were any other clubs or TVs who meet and indulge each other apart from the Beaumont Society, a self-help group for transvestites and transsexuals.

MJ working on an oil tanker, wrote in hurried and scribbled script as he was about to dock in Aberdeen, that he would be on leave on 15 September 1973 and wondered if it would be possible to meet for a drink and a chat. He had been bored with everything and wanted to be introduced to someone. He couldn't find anyone himself and wasn‘t sure whether it was embarrassment or not. What could he do?

Micky Burbidge, the founding member of Icebreakers, answered a letter on 20th September 1973 from GA of Royston, a would-be helper. He was 25 and described himself as an unmarried bisexual with some experience of counselling and guidance of young people. He had seen an article in Gay News about the aims of Icebreakers but had reservations about encouraging homosexuality in the young. He felt it would move them unnecessarily away from heterosexuality. A meeting was arranged.

Nettie Pollard was a member of the GLF counter psychiatry group in the 1970s

Nettie Pollard at the 50th anniversary celebration of the Gay Liberation Front (2020)

A letter dated 2 March 1974 was received from a 45 year old married man with children. His wife knew that he was gay and accepted it. He had answered one or two advertisements in Gay News but without success. He stated that although he was a family man he felt very lonely. He had not as yet experienced a relationship with another man and felt very green about the whole thing. He suggested that it would be possible for someone to spend the weekend with him and he preferred a younger man.

Gary de Vere in 1970s, now deceased

In connections with Icebreakers an article appeared in the Hackney Gazette of 5 July 1974 bearing the title: 'Who wants to be like Blanche?'. The reporter used this reference to the main character in 'A Streetcar Named Desire', a play by Tennessee Williams, to illustrate the need for organizations like Icebreakers. Blanche married a man at 16 who turned out to be homosexual.

Icebreakers challenged the approach of 'Agony Aunt' Marjorie Proops. Her column in the Daily Mirror was replete with anxious and fretful 'personal’ problems of the confused and worried kind. As the number one agony aunt pondered the problems of marital and sexual dislocation did she really take into account the needs of homosexuals? An Icebreakers leaflet was promptly dispatched to her as well as to many other newspapers and dear Marge promised to keep a copy by her side when answering letters from her readers. She would do anything to alleviate the distress and ignorance surrounding homosexuals and wished to make life a little happier for them. This neglect of gay needs and patronising attitude did in part justify the need for organisations like Icebreakers.

Just how radical was Icebreakers as an Organization? Clearly it could not be as open and militant as the South London Gay Liberation Front. The very nature of the work that it did of necessity encouraged a certain amount of secrecy to protect those who were just coming to terms with their LGBT+ identity and it had initially to facilitate that coming out in an atmosphere of privacy, security and trust. Yet the whole orientation of the group was towards ideas gleaned from Gay Liberation with the emphasis on difference and pride rather than the liberal ideal of a spurious integration and consequent descent into respectability and loss of identity.

There were also tricky situations to negotiate. In the guidance notes for volunteers, lcebreakers warned against the dangers of bogus phone calls. With the threat of Police entrapment and gutter journalists posing as genuine callers wanting to meet someone caution had to be exercised especially around questions of ‘under age‘ sex. In the final analysis Icebreakers helped a considerable number of LGBT+ people to come out and enabled them to participate more fully in the gay community. To live a life without guilt, shame and fear thus breaking through the boundaries set by straight, respectable conventions with the possibility of bringing people into a more politically active milieu surely qualifies Icebreakers’ approach as more than just glorified social work. That is why the activists in the South London Gay Liberation Front were willing to become involved as volunteers.

Stickers for plastering on bus stops, tube trains, public notice broads, any place where people congregated though British telecom threatened prosecution for unauthorised use of their telephone boxes.