Originally I had intended to produce a full-length book about this period in LGBT+ history. That was back in the mid 1990s when I was working full time and pursuing a degree course at Birkbeck College, London University. The work load proved to be too burdensome and I had to abandon the project. However, time and technology have moved on which means now that I have retired I am able to spend more time on this project with an entirely different approach. With websites now the norm it is possible for me to produce a written account of this period accompanied by a large collection of photographs, posters, flyers and leaflets which would have been prohibitively expensive in book form, not least to mention the loss of materials from podcasts and videos. The website also has the additional advantages of being free of charge to view and a global audience within easy reach.

This account is not theory laden, nor does it claim to be a comprehensive social history of the exploits of individuals and organisations in the struggle for gay liberation. It is more of a photographic essay, giving a brief snapshot of the South London Gay Community Centre and the gay squatting community in Brixton in the period roughly from 1974 to 1981. The final year, 1981, was marked by the devastating experiences of the Brixton Uprising against the racist oppression and violence meted out by the Metropolitan Police. 1981 saw the winding down of the gay squats and the growing menace of the AIDS epidemic that took the lives of so many of our lovers, housemates, and friends in the following years. Unemployment, especially among black youth, the housing crisis, and environmental decay and social deprivation.

The 1980s in many respects was one of the bleakest periods in history for gay men in the UK. The police increasingly continued to raid gay bars, clubs, saunas, cottages and cruising grounds and did not fight shy of using entrapment to lure gay men into committing victimless 'crimes'. Scare stories about the murder of a boy scout in Bradford, far away in Yorkshire, or pedophile rings nationally, only increased police surveillance, harassment and arrests. Margaret Thatcher's government added to the repression with section 28 of the Local Government Act. This law forbade the promotion of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship by local government and schools at a time when the AIDS epidemic was in full flood and support should have been given to the victims. In accordance with a return to ‘Victorian values’ Thatcher also opposed advertisement about safer sex on the grounds that it would encourage sexual activity among gay men. This only served to increase the stigma, fear and panic around what was portrayed as the 'Gay Plague' when gay men were dying with little appropriate health care or social support.

In keeping with the spirit of the times James Anderton, Chief Constable of Greater Manchester police, aired his religious convictions by banning gay men’s ‘licentious dancing’ in nightclubs and denouncing those who were HIV positive as “swirling in a human cesspit of their own making” which only served to reinforce the stigma and fear around the illness and increased the already profound isolation and neglect that gay men were suffering.

Jeremy Thorpe was forced to resign as leader of the Liberal Party and lost his seat as member of Parliament for North Devon. Arriving at the Old Bailey on charges of conspiracy and incitement to murder Norman Scott, his former gay lover, Brixton Gays picketed the court to challenge the notion of Thorpe's homosexuality as being a 'fatal flaw' in his character and to exhort him to come clean and 'come out' proudly as gay (1979)

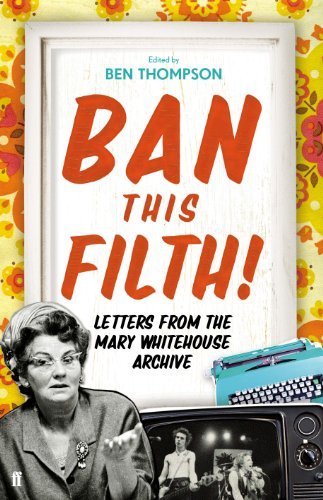

The 1970s was 'another country' compared to the 1980s. That's not to say that repression did not exist. Despite the limited law reform of 1967 and the continuing efforts of both the Campaign for Homosexual Equality the Gay Liberation Front to challenge legal discrimination and oppression in education, law, employment, healthcare and the media repression continued to mount. Amidst wider social disapproval, the police actively attacked gay places and ruined many lives with vexatious prosecutions. Public exposure led to gay men losing friends, family and jobs. Crusaders against moral pollution such as the 'Festival of light' (renamed by Gay Liberationists as the 'Festival of Blight') and Mary Whitehouse's harmless sounding 'Viewers and Listeners Association' culminated in the successful prosecution of 'Gay News' using the ancient law of blasphemous libel and media censorship of pop songs by the Sex Pistols among others. The Jeremy Thorpe scandal and trial highlighted the dire consequences of having to remain secretive about homosexual relationships and only served to reinforce just how unfree homosexuals were especially in public office. There were attacks on gay venues and individuals by fascist organisations such as the National Front. The positive side to all of this is that it did provoke a huge fightback by gay organisations that formed various defence groups and direct action 'zaps' to challenge our oppression. The National Gay News Defence Committee and the Gay Activists Alliance were a response to this.

Mary Whitehouse rallying to the cause of Christian moral values at the 'Festival of Light' and outside the BBC. As the leading light of the 'Viewers and Listeners Association' her crusade for moral purity badgered the media to change its sinful ways to end sexual permissiveness and moral pollution. Her campaign had little effect though she famously and successfully prosecuted 'Gay News' on the charge of blasphemous libel. Early to late 1970s.

Besides fighting back against particular forms of oppression in the 1970s there was still a heightened spirit of experimentation in alternative ways of living and politicking. The struggle of gay men in 1980s was of necessity mostly a defensive one despite the fight back against section 28* and the great exception of Lesbians and Gays Support the miners during the strike of 1984/85 which clearly aligned gay people with working class struggles. The AIDS epidemic had understandably taken the energy of many gay activists away from wider campaigning on a whole range of social justice issues to campaigning against a recalcitrant government that refused to take the epidemic seriously, to challenging widespread ignorance and prejudice against AIDS sufferers, to producing safer sex education and to setting up respite centres for those affected by the HIV virus.

I hope that what I have done in this account is rescue a lively period in the LGBT+ past (mostly gay male) from oblivion, avoiding the fate of many radical moments of being hidden from history. My main aim has been to dig up what would otherwise remain buried forever in people's unopened memories or simply salted away in unused archives without seeing the light of day. I am also interested in capturing those more fugitive moments of short duration for a more 'lived' feel as history-in--the-making. To achieve this, besides oral testimonies, there will be many photographs, flyers, leaflets, posters, and art works to accompany the written text. This material can point to wider narratives and should not simply be airily dismissed or trivialised as ephemera.

In reconstructing an otherwise buried past my main approach is to raise questions about the period under consideration. What were the strengths and weaknesses, successes and failures of the gay 'community' in Brixton from the early 70s and 80s. I am using the term community in a very loose sense meaning a community of interest in fighting against LGBT+ oppression. Clearly there were differences in class, gender, income, nationality, political outlook, and race, in the gay squats and it would be a mistake to pretend that those differences did not lead to tensions however unspoken or understated they may have been.

I am well aware of the paucity of detail about lesbians, trans people, and gender non-conforming people. The squats were overwhelmingly occupied by gay men who were preoccupied with political issues, living arrangements and lifestyles around gay men. There were few references beyond those considerations. Given the squats were heavily male-orientated, dealing with issues and lifestyles around gay men, it isn't surprising that the atmosphere was uncongenial to lesbians and others whose interests and fight against oppression lay elsewhere. At the time many radical lesbians preferred either to become part of the wider Women's Liberation Movement or to set up separatist enclaves in a total challenge to patriarchal values. There were social and counselling groups for transpeople but the political fight for Trans rights was practically non-existent.

In producing this 'snapshot' I wish to raise several questions. Could any valuable lessons in political radicalism be learned from that period that would be of relevance to contemporary LGBT+ politics and is there a need to build a new movement of active LGBT+ people in the wake of unresolved political problems? If so what relationship should that movement have to the wider class struggle of workers and women, BAME and other oppressed groups. Or is the fight for Gay Liberation over and done with given the huge strides in political and social reforms over the years? At least in the more liberal 'western' nations.

To begin with there will be chapters on the wider background of national political events and the more local situation on squatting, the housing crisis and how this affected LGBT+ people in Lambeth at the time. Four moments of early LGBT+ manifestations in Lambeth prior to squatting the South London Gay Community Centre and gay households will help to place this history in a broader context indicating earlier LGBT+ activity in Brixton and their consequences before the main narrative begins.

I hope I have managed to answer the questions raised above and I leave it to the reader to make a judgment on that. As ever any mistakes and omissions in this history fall entirely on my shoulders.