In the 1970s alternative community-run newspapers often equipped people with the skills needed to edit and write for them. They also taught people how to do the layout and printing and reflected the views of those who had been marginalised and voiceless including articles by the South London Gay Liberation Front

Alastair Kerr from the Brixton gay squats holds up a Fairies Against Fascism placard to protest against the National Front's local election meeting on the Angell Town estate, Brixton (1976)

Bearing in mind that this history takes place in the days before computers and mobile phones the main channels of communication for gay liberation activists was either straight newspapers or gay publications or very rare television and radio public access programmes. It would be untrue to say that the local newspapers went out of their way to publicise the gay centre but many would print anything sent to them to fill a shortage of exciting newsworthy items in what were perceived as rather dull and pedestrian publications.

The South London Press and other smaller local newspapers pursued a fairly liberal policy on the coverage of gay issues with the help of a gay journalist at the SLP as did the Daily Mirror with sympathetic coverage from Marjorie Proops as Agony-Aunt-in-Residence. The gutter press stayed in the gutter with its prurient sensationalism designed to bolster and confirm the prejudices and stereotypes of what it believed were the particular prejudices of its readership. The respectable press stuck to its moralising certitudes about normality being the best way in an effort to stay within the boundaries of its market appeal. But for gay people to exert direct control over news coverage the only available forum at the time, apart from Gay News, the Guardian or the odd letter or two in Time Out, were community based newspapers and self-generated leaflets and posters for distribution through our limited channels of communication.

National Front's local election meeting on the Angell Town estate, Brixton (1976)

Community papers came and went like shooting stars with only small traces of them left behind either hidden away in people's fading memories or buried deep in forgotten public and personal archives. Many of them offered space to various groups and individuals to sound off practically on any subject they chose. The opportunity was taken to put forward the case for the SLGLF in an article which appeared on 3 July 1973 in The Street a community newspaper based in Streatham. The paper directed its attention towards issues affecting minority groups and local communities ignored by the mainstream media. Practically anyone interested in community issues was given the opportunity to assist in putting the paper together including writing, layout and printing and any cartoons or articles submitted were published virtually unedited. The point of all this was to de-mystify the whole process of writing, printing and publishing by providing a more democratic practice and setting in which to develop those skills by making them available to everyone with an interest in developing the community for the better. The main challenges were to the status quo of poverty and social deprivation.

A reporter for the Times Diary visited the South London Gay Community Centre and interviewed the SLGLF Candidate during the 1974 General Election Campaign in what he described as a "shabby set of rooms in Brixton's black area".

The people involved in producing the community-based papers generally refused a strong ideological line fearing that would destroy its status as a paper in which ordinary members of the community could participate without the baggage of political perspectives set in concrete. They were willing to negotiate the tyranny of loosely organised collective editorial meetings with the possibility of an aggregate of different individuals each time. The left castigated it for parochialism and for avoiding a solid commitment to revolutionary (marxist) principles. But what revolution could possibly be built upon anything other than real, street-level solidarity, real community, argued the ‘editorial collective’? This left ‘libertarian’ stance allowed articles to be accepted from the most diverse of sources. There were indeed drawbacks in the lack of editorial coherence necessary to mount an effective fight to build a better community in which to live. But it did empower those who would otherwise have been marginalised and ignored by equipping them with the skills and collective spirit to fight back. To illustrate the eclectic mix of articles and to make the point more clearly one issue of the Street included:

Publicity shot inside the South London Gay Community Centre for The London Programme an early public access television series (1975) Scripts below. Left top to bottom Alastair Kerr, Colm Clifford, Gary de Vere, right top to bottom: Tony Reynolds, David Dilemma, and Ian Townson

Young Liberals who wished to campaign for the removal of Duncan Sandys MP. Squatting groups attempting to house homeless people by occupying empty properties. Harassed Communist Party paper sellers in trouble with the police. Black radicals and other revolutionary groups struggling against a long period of intimidation of the black community by the police and courts. A ‘love in’ rock festival enthusiast advertising the Windsor Free Festival. Action for the disabled. Short story writers. An irate tenant's letter to a landlord attacking him for his lack of responsibility towards his tenants. The Children of God. The National Union of School Students on strike. The Sackville Estate Children's‘ group campaigning for a youth centre. A claimants’ union giving advice and encouragement to self-activity for those experiencing difficulties on welfare benefits. A short piece on the charming mice of Streatham Hill. An alternative society ideas pool. An alternative media page. A write up on an all-woman rock band called Fanny. Puzzles and competitions. A letters page and of course an article about the South London Gay Liberation Front.

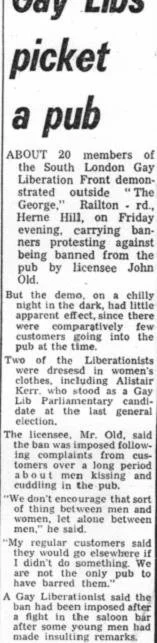

South London Press 1974

Streatham News

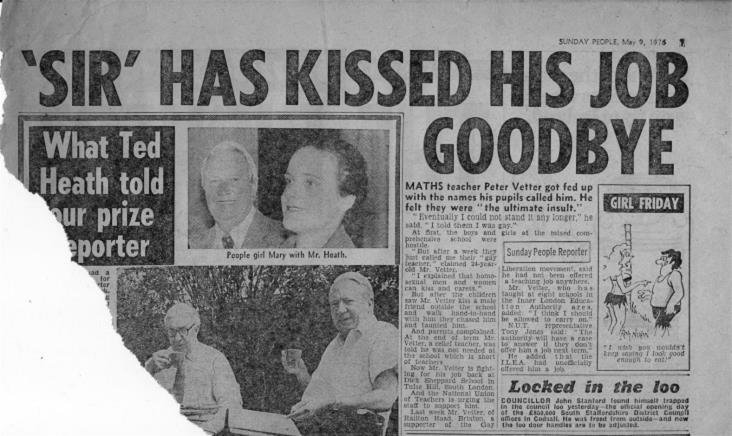

Peter Vetter loses his job as a teacher at Dick Sheppard school, Tulse Hill, Lambeth (1976)

Apart from statements along similar lines to the Gay Liberation Front manifesto which gave a brief analysis of gay oppression and emphasised solidarity with the women's movement and other oppressed minority groups an important point had been stressed which later became a bone of contention. On being asked if heterosexuals were allowed in to use the South London Gay Community Centre one a SLGLF member said: "Why not‘? Heterosexuals are just as welcome as homosexuals. We don't practice discrimination." This stance did not last and the gay centre became a battle ground for a hetero-free zone to make it more hospitable and gay friendly for those who were just coming to terms with their sexuality.

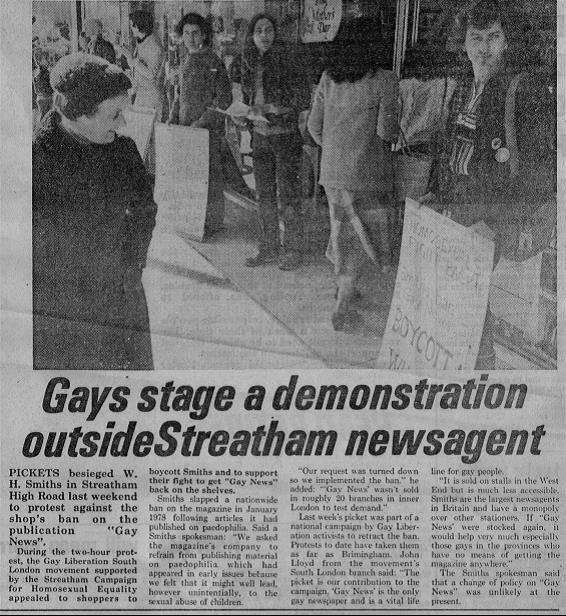

Liberal magazines such as Gay News and Time Out also advertised gay social venues, political groups and contact ads among other things. But some South London Gay Liberationists castigated the established gay press for its timid approach to challenging oppression, especially self-censorship indulged in under pressure from more conservative influences. This usually began as a serious bid by gay centre activists to take up what was felt to be a cowardly evasion of ‘controversial’ issues on the part of the paper. But often this ended up in an unwitting comedy of furious indignation mixed with more serious accusations. Here is an example involving the controversy about Helmut’s genitals:

In a letter to Gay News dated l3 July 1973 Gary de Vere, on behalf the SLGLF, complained about an issue close to his heart and surely of many gay men. He complained that Mary Whitehouse, Lord Longford and legions of the self-righteous could not have done a better job of censorship than this wanton act of mutilation.

The ill-tempered letter continued with apoplectic twists and turns in stricken attitudes of disbelief. The second paragraph began with: “What on earth is the matter with you”, a sure sign that some momentous pronouncement was about to follow. The invective continued in the following vein:

“Would Gay news, in pandering to respectable standards of decency which oppress all gay people, serve the cause of gay liberation by obliterating Helmut’s cock? How far would the editorial group go to accommodate the wishes of a minority of uptight readers‘? Would they drop all articles on police harassment simply on the grounds that the constabulary are a fine body of men doing a great job under extremely difficult circumstances‘? Do you also believe that matters could only be made worse by showing a lack of respect towards them.”

But above all what might have been a pleasantly erotic photograph of the naked Helmut had been ruined by genitals made ridiculously absent by a castrating, stuck-on star shape. This intrusive Victorian fig leaf meant that Gay News had simply failed to be disgraceful at a time when an outbreak of wickedness and outraging public decency would have been welcomed; a challenge to the censorship of an uptight ‘straight’ morality that demanded genital mutilation as part of its godly world view of things.

The South London Press and smaller local newspapers gave muted coverage to the SLGLF's 1974 local and general election campaigns and the refusal of the ILEA to allow a gay studies course. The SLP also covered the eventual eviction of the GC with a Larry Grayson style healine of “Not such a gay day for the gays”.

The SLGLF participated in areas opened up by Lambeth Council in its bid for greater democratic accountability but this was not a smooth marriage of unproblematic bliss. In a letter to Jim Scott, dated 19 November 1973, Elizabeth M Wallis of the Council for Community Relations in Lambeth wondered why Mr. A Salvis no longer attended meetings. He had been elected to the Executive Committee and other sub-committees at the councils inaugural meeting back in July of that year but had not been seen since. Any news of his whereabouts? Agendas and letters had been sent to his home address but to no avail. What this illustrates is the lack of enforceable discipline and commitment on the part of the SLGLF to mandate responsible members to carry out the role allotted to them.

Original script

Final script