PLEASE NOTE: This section is still very much a work in progress. Some of the interviews are incomplete and have been edited for greater coherence and clarity. Their fragmentary nature is a reflection of the varying and sometimes poor quality of the taped interviews and some have proved to be almost inaudible hence the need to interpret their meaning. Not all of the audio tapes have been transcribed yet. Please come back again in the future, from time to time, as we add more testimonies. I have also used parts of the interviews in other sections of this website.

ALASTAIR KERR'S REVAMPED INTERVIEW by Ian Townson from the Peter Bradley 1980 interview

With very few friends and little social life his university days were spent 'sexually' in the closet. He was always camp and outrageously dressed ‘fancy’ clothes as his main outlet and pleasure. He was never conscious of meeting anyone who was gay and whenever anyone 'gave him the eye' he thought they were being hostile.

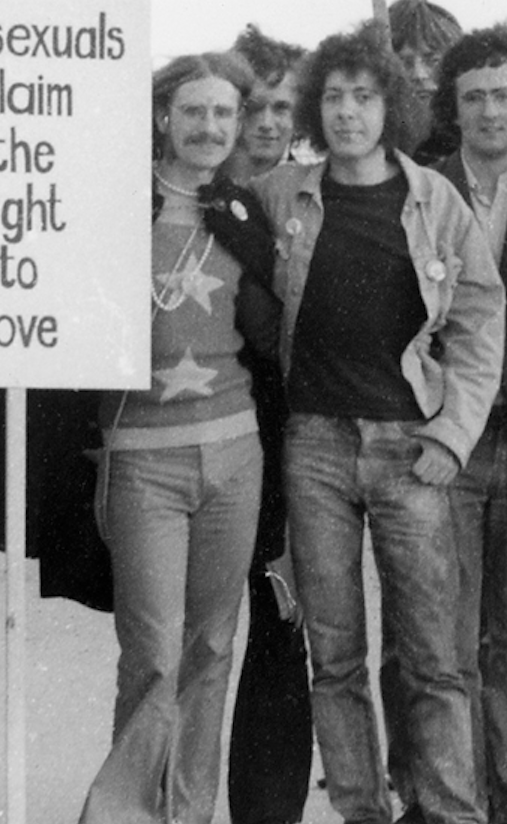

Alastair on our left on his first protest for LGBT+ rights with Susses GLF in Brighton (1972). Others unknown

Answering an enquiry at the South London Gay Community Centre (1975)

Alastair Kerr was born in 1946 in Glasgow but spent most of his life living in England. When he was just a year or two old the family moved first to Lytham St. Annes for about ten or eleven years then to Durham where he did all of his secondary schooling at a grammar school. After finishing his 'A' levels and an MA at the university he spent 'a few years' at the art school. He finished there in about 1970 and headed south to Brighton for a teacher training course where he came into contact with the gay liberation group. This first contact with gay liberationists meant that he was able to come out completely.

He came up to London and lived in a house with straight people on Brixton Hill from about 1973. He took up with one or two boyfriends and had a lover for about eighteen months. In July 1974 he left him in order to live above the South London Gay Community Centre where he became its unofficial caretaker. All the time he had been in London he worked at the London College of Printing at the Elephant and Castle (Now the University College of Arts and Communication) teaching the history of art and design to graphic design students.

His father, who he never got on with, retired from a successful career in the Ministry of Agriculture. His mother died when he was about eleven years old and his father remarried in 1965 or 1966. He got on very well with his mother but neither he nor his brothers liked their stepmother. Both brothers seemed to take it in their stride that he was gay and the younger one had gay friends though in retrospect he felt his brothers, especially the older one, were the household "male chauvinist pigs. I mean, macho as it were."

From a very early age he felt sexually different from other people and always felt as though he was being 'cheated and stared at' for not being like other boys. He was always interested in creative things including art and reading but was plagued by others making 'sissy' remarks about him. He was jeered at because he wanted to be a dancer rather than taking up the usual pursuits of boys such as football and other sports which he viewed as 'a futile waste of time.' He never got his dancing lessons but he was unsure if his parents didn't want that or they could not afford them. He was sent off to piano classes instead which he reluctantly took up.

His earliest sexual awakening happened at school when he was about ten years old having mutual masturbation sessions with other boys. His anxiety around this arose much later when he was in the sixth form. He was 'chased after' by another boy who shunned any attempt at further intimacy. His need for affection was not met. The encounter was 'brusque' and unsatisfying and laced with fears of being discovered that would only add to being castigated for his 'sissiness'.

At the age of about thirteen or fourteen during a school line up in the playground he clearly remembered his first dawning awareness of being gay by just saying to himself "You're homosexual." The word queer or gay never meant anything to him at the time and surprisingly he seemed to accept calmly the fact that he was different. It was only later he began to feel anxieties about being gay with increasingly jeering reactions from 'yobbo type boys' especially sixteen to eighteen year olds in the sixth form because he was seen as such a sissy.

Alastair was a 'fish out of water' because he wanted to dress in 'fashionable styles' which went against the grain of what was permissible in the 'dour' north east of England which he viewed as a "dump" compared to the mellow Lytham St. Annes. He felt that his chances of a more bearable situation would have been made possible in the more liberal atmosphere of London where he could live among a "fashionable clique of kids." His parents continuing lack of engagement with the kind of things he was interested in happened at a time in his life when he needed that extra 'push' from them to discover and become involved in theatre and music events scarce though they were.

In his efforts to find out more information about being gay Alastair scoured the bookshops for clues. He came across James Baldwin's 'Giovanni's Room' which he stole from a 'store for sexual perversion' because he was too frightened to be seen buying it. In retrospect he felt the book was so negative that it kept him in the closet for years. The message he took from the book was "avoid homosexual life like the plague and at least you might be alright. You might have the title of the disease but you will be alright so long as you keep away from those sort of people."

Despite having gone through primary and secondary school where he was bullied by 'aggressive louts' he had high hopes that university life would be free from 'oppressive male chauvinist sexist attitudes'. He imagined that the higher up the academic tree he went the more "cultured, nice and civilised" people would be. His experience of drunken yobs in the men's union bar disabused him of those hopes. The jeering and mockery continued because of his flamboyant behaviour and outrageously camp dress sense. He dealt with the whistling, yelling, snickers and sneers in Quentin Crisp style by walking straight through people and looking straight ahead without flinching. His whole university life in terms of study and socialising were completely marred by having to deal with this anti-gay prejudice and posturing.

With very few friends and little social life his university days were spent 'sexually' in the closet. He was always camp and outrageously dressed in fashionable and fancy clothes as his main outlet and pleasure. He was never conscious of meeting anyone who was gay and whenever anyone 'gave him the eye' he thought they were being hostile. As a student he went to Grimsby in 1968/69 for two summer seasons to help with harvesting crops at a nearby farm. It was here that he had his first significant sexual encounter as an adult. He was sexually fired up after five or six weeks hard work and, on wandering into a cottage in a local park, he noticed gay graffiti on the walls. He returned a few times to read it all again and decided to try his luck in meeting someone there. The encounter was 'sleazy' with little interest from the man he met but he felt that he 'just wanted the experience.' It was only later, in retrospect, that he realised that a man had actually cruised him in the university cottage.

Feeling low in spirit he decided to visit a psychiatrist in 1967 having heard by chance that someone who had a breakdown had found that experience helpful. He wanted to stop being gay and was referred to the University Medical Centre. The Indian doctor he visited said that it could be done. Alastair saw the advantage of talking to someone about 'it' but in the end the advice he received was entirely useless. He kept seeing the psychiatrist who identified Alastair's problem as largely being social in origin and one of social inhibition. Going to parties and dancing with girls was prescribed and 'you can get out of it' type of games were played out. At the end of the sessions an encouraging handshake for his bright future as a heterosexual were not reassuring. The shyness and inhibition when meeting people were still there because of his past experiences of being rejected and ridiculed from early life onwards. He never followed up, as a possible source of help, the rumour that the Roman Catholic chaplain was gay and sympathetic. Nor did he feel able to be involved in cruising around the university library. He continued to feel guilty about being "an absolute Lulu queen."

The only informative chat about being gay and a slight thawing of negative feelings came in his last year at university through conversations with a man he shared lodgings with in a straight household. He talked a lot about sex and intimated that both he and Alastair might be bisexual. He he talked about the pretty boys he had sex with at school. Later Alastair met him again at the Design History Group that he was teaching and it transpired that he was married with children. Alastair met one woman student who was sympathetic because she had a friend who was homosexual. Later through his work with Icebreakers, a radical gay counselling group, he became aware of how many students made contact just before leaving university with anxieties about their gayness, how to deal with it and who to contact.

In the late 1960s he was aware of underground, counter culture magazines that carried gay contact ads and his indulgence in porn consisted of secretly reading and concealing from view 'health and strength, muscle building' magazines. As an 'outsider' he even rejected the hippie movement that came into existence from the mid sixties onwards. He felt the 'hippie mentality' was 'complacent' and no different from straight society. He rejected the drug culture because he felt weak and vulnerable already and did not want to make his life even more 'befuddled' or bewildered.

He was vaguely aware of the 1967 Act which partially decriminalised homosexuality. It came to his notice in 1967 when driving through England on his way to a holiday in Spain. He saw a notice written up somewhere in huge letters 'Stop the Queer Bill' but was unclear whether it referred to him or not. Later he observed that the passing of the bill clearly made no difference at all to the way he or anyone else was treated.

By 1971 he had moved to Brighton to take up a teacher training course and grown in confidence. He discovered a cruising ground and after one or two weeks he met and slept with a 'strong' man he had fallen in love with though the relationship never lasted. He started cruising much more instead of wandering aimlessly around town 'looking at antique shops.' though he felt his academic and cultural life suffered as a result of cruising. Despite this he started to go to gay bars more. He had heard about them from friends in Edinburgh but found the people there inhospitable and was put off by their 'game playing'.

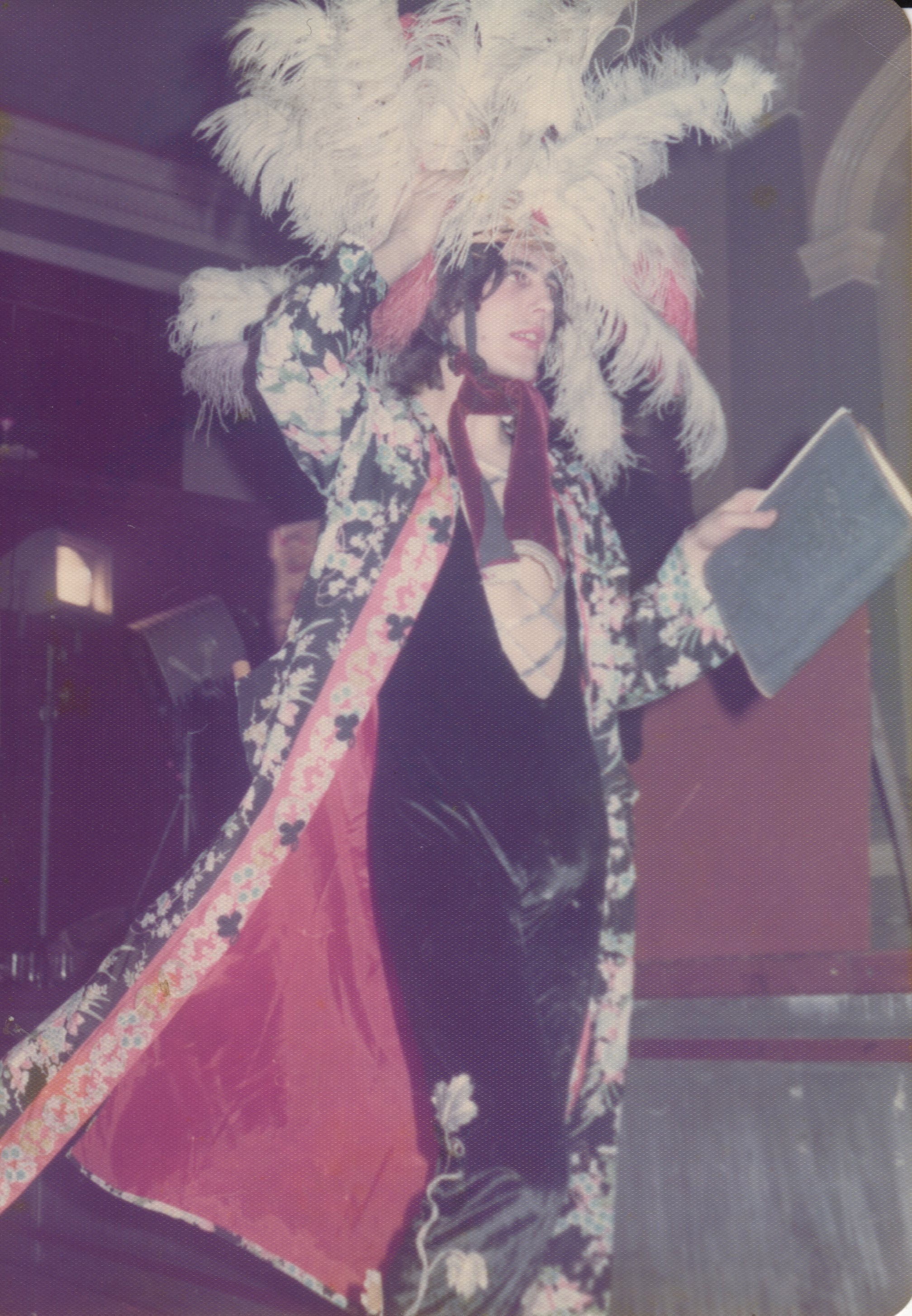

In the same year he had moved down to Brighton he meet 'a black man' in a gay bar who told him about the local GLF group. Though it was small he found the group full of 'intelligent thinking people who wanted to do something about homosexuality for themselves and other gay people.' He read about people involved in GLF London and when they were invited to Brighton their political analysis and radical ideas opened up Alastair's awareness of why he was being oppressed. With talk of sexism, feminism and challenges to Patriarchy he placed his own experience of being attacked for being a sissy in the wider context of women's oppression and male chauvinism. Hence by the end of his teacher training course in 1972 he had completely come out as gay. From then on in the age of David Bowie and wearing his own glittering apparel, make up and nail polish he felt empowered and strong enough to go on the offensive around Brighton with others to 'freak people out' and demand gay rights.

By the time he arrived in London he was determined to be out as gay right from the start especially at the college where he would be teaching. He hitch hiked there with no solid thoughts on where to live. It was only by a sheer fluke that he got a place on Brixton Hill via a contact at 'Time Out' magazine. The flat was near Brixton Water Lane which was a notorious cruising ground for sex workers. He shared the flat with straights but didn't get on with them.

Alastair's own words on coming out:

"Well, there I was at the London College of Printing being an outrageous queen wearing badges and jewellery and glitter and all the rest of it......people just stared and gawped and sniggered and yelled and so on but at the same time I was left alone and completely ignored. Very lonely.....a typical straight reaction to gays. They both freak out and at the same time succeed in totally ignoring you."

He was determined to pre-empt all the usual insults he received by throwing it back in people's faces and making it their problem not his. By wearing eye makeup, multi-coloured nails with jewellery while sporting hennaed hair and moustache he deliberately challenged gender and sex role stereotypes. He continued this for three solid year from 1973 to 1976 and took some comfort and fun in the bewildered reaction of students and staff. The bitterness was dissolving.

Alastair had many narrow escapes from being beaten up but this occurred only once at college. Even so it left him with the feeling that he was not safe anywhere and he nearly broke down:

"That was when someone followed me down a corridor and I finally managed to rush downstairs and drop into my room before they knew where I had gone. I locked the door."

He set up the GaySoc and a disco in 1973 but the meetings were poorly attended, "a complete flop" and the discos could not compete with the growing number of gay pubs and clubs opening up. He was disappointed that during his three year's as a teacher he had scant success in bringing any students or staff members out as gay. After he had left the college he met a student who came out and experienced the same difficulties in organising the GaySoc and disco. Alastair attributed this failure partly to the fact that "there was no space within my curriculum to talk about gay identity and sexuality." Also he judged the graphic design students, who were predominantly straight, as being "amoral and asocial. Living by example as being someone who is out as gay...doesn't seem to cut any ice with them because they never think philosophically. They never think about these issues...a tiny minority maybe...almost always women."

What Alastair pointed to was a lack of any rigorous academic culture and questioning of the the world and its ways that were to be found in other higher education institutions such as universities. His cynical views about students were driven by the belief that the narrow focus on technical training as graphic designers geared towards the commercial world they would be working in stripped them of any awareness or interest in human affairs beyond their career expectations.

Alex Beyer Interviewed by Ian Townson - 11/05/1997

To be frank I was frightened. In my world I couldn’t come out as a taxi driver. I mean they'd just be unmerciful if I was to come out. So I had to stay in the closet. If I had been brave I could (have come out) but I wasn’t that brave. I was afraid quite often that people would discover that I was gay....

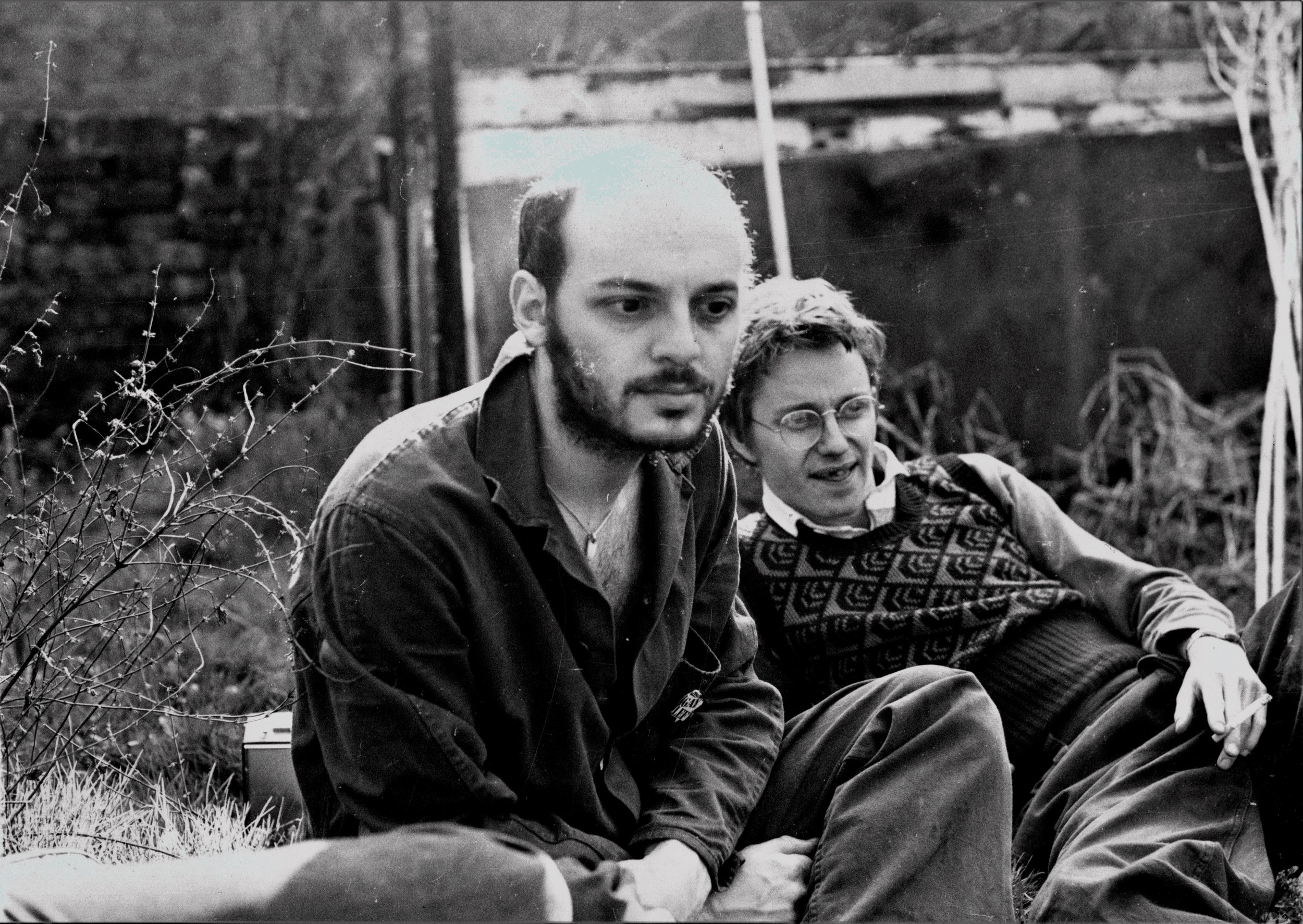

Alex on our left with Dennis Simmonds his long-time partner of over 20 years (deceased)

ALEX BEYER was born in Cheltenham on the 20th October 1941. His father was German and came to England to escape the Nazi regime because his mother was Jewish. It was revealed later that she had died in Auschwitz concentration camp. His father was interned as an enemy alien before joining the British Army in the Pioneer Corps a position open to internees who were not felt to be a threat.

"He wanted to study under Eric Gill the famous sculptor. In some of his work he designed typefaces and also he (Eric Gill) did some sculpture above the BBC in London, Portland Place. He was apprenticed to him for I don't know how long but he lived with Eric Gill for some time. I think he came to this country when he was about sixteen or seventeen."

Alex's three sisters worked at various occupations ranging from odd jobs in a paper shop, a nursing auxiliary, clerical work and teaching languages, alternative medicine and owning a sheep farm in Wales. His parents both became teachers in private schools and later his father became involved in masonry and sculpture. He was clear that religion and politics did not play any prominent part in family life.

Alex first became aware of being gay when he lived in Cambridge at about the age of twelve or thirteen when he met boys that he fancied and "played around with".

After living in several different towns and cities in the Midlands and South the family moved to Bellingham in London around 1952/3 later switching to Dulwich in 1954 on another council house exchange. At this time family life became less harmonious when his father deserted them:

"...my dad had a bit of a roving eye. He was looking at other women and left home a couple of times. Obviously that upset my mother but she had him back once or twice. The thrid time he went off again and she didn't have him back the third time."

Alex lived in Dulwich from 1954 to 1970 and it was here that he had his first gay relationship though he was unaware of any gay politics and remained closeted:

"From 1954 I did all sorts of jobs as diverse as a farm hand, I worked in factories and did clerical work. I met a guy who lived on the estate where we lived. I fell madly in love with Peter? In 1959 his father was working on the buildings. His stepmother wasn't really interested in him. She buggered off back to Yorkshire where she came from. He invited me to move in with him. So we moved in to a flat together. We lived there for about a couple of years. That was quite pleasant in some ways but it was bit stormy....He didn't acknowledge it as a gay relationship. The term hadn't even been invented really in 1959. It was just two guys living together that liked each other. We used to have sex and that. It was very pleasant but we had a lot of rows. He didn't go to work. He didn't really want to work but he was very clever at technical things and he used to occupy himself doing that to get money and I used to work which caused envy? because I was working and he wasn't. So that was '59 to about '61/'62."

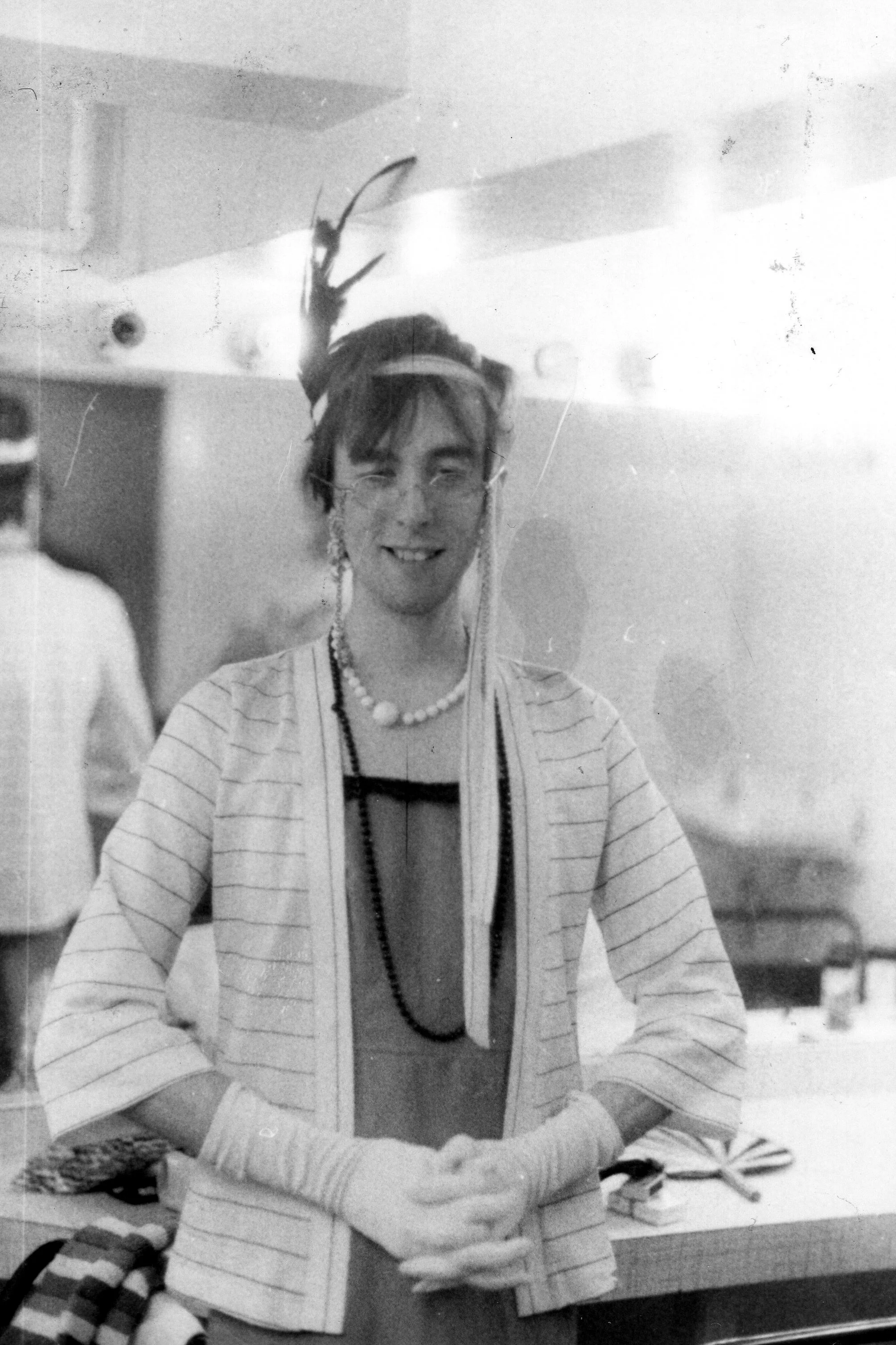

"Then I moved to another flat in Gypsy Hill, near Crystal Palace, and lived there on my own for about another 8 years. All my gay experiences sort of were furtive. Perhaps a bit of cottaging, picking people up there. But funnily enough the girl who let the flat to me, she was an impoverished painter, was a lesbian. Through her I met some gay people who were involved in amateur drama. In 1962 when I moved there I was only 21. Some of these guys in the drama group, they were all gay, and took a fancy to me. They encouraged me to join the group which I did. I enjoyed being in the group. I could identify with them as being gay and that. That was quite interesting. So I met some gay people through that."

"....I took to them and I got involved in the plays. There were l think a few straight people but it was predominantly gay and it was a lot of fun. I didn't think of myself as an actor. First of all I started doing back stage work and then they said, look, we need bodies for Shakespeare. I said that I'd never acted and they just said, well give it a try. From then I've never looked back. From that point onwards I used to everything from pantomime to Shakespeare. We used to perform at Lambeth Town Hall and Southwark and....it was a lot of fun really. Also the social life, being gay, l took to that like a duck to water. Even though many of them were much older....there weren't that many young people. I was only in my early twenties and they were in their late 30s early 40s."

Alex moved from Gypsy Hill further afield to Sydenham:

"Then the lesbian woman who let the flat....l left for some reason and then l decided I didn't like where I was living and I wanted to go back but in the interim she'd let the room and couldn't re-let it to me. Her brother had a room and l was so keen to get back into the house because it was a bit of a bohemian atmosphere, she being a painter, and it was all very laid back. So he said, I'll let you use my room. But that was a bad move because of her limited income. She was just living on the poverty line. Just existing on what paintings she could sell. She wasn't deriving any income from me anymore so then there was a lot of friction and resentment because her brother didn't give the rent to her which l think he should have done. He was working. He could have said, look you've got no income, you have the rent. He kept the money and she was so resentful that there was a lot of friction and then she used to start on me. She used to take drugs and drink. She was alright when she wasn't drinking. When she drank she used to get very, very aggressive and she threatened me with a knife one day. I said, well that's it. I'm not staying here any longer. I asked a friend....most of my friends at that time were gay....and he knew someone who had a room in Sydenham, a gay fellah. He asked him if it was vacant and as it happened it was. He said he was happy to let it. l went along and took it. That was around 1972 and was there until about 1975."

Alex clearly remembers his first encounters with the Gay Centre in the Autumn of 1975. He started as a taxi driver in the Croydon area in I972 and from 1974 earned his green badge after doing the 'knowledge' and became a fully-fledged all London black cab driver. The Croydon period afforded interesting and fruitful encounters in certain of the boroughs cottages which stayed open all night:

"....I was an inveterate cottager. All their cottages for some reason were open all night....so you could go out at night and do the rounds of the cottages which were pretty active at the time. So that's what I used to do during the night (laughter)."

On one or two occasions he had passed the Centre on his way along Railton Road. But it was his meeting with Malcolm Greatbanks at Waterloo Station that clinched his interest in the Centre. He had stopped at a stall for a cup of tea and had just pulled out when Malcolm hailed him. In those days it was almost impossible to get taxi drivers to take anyone to Brixton. Such was the media portrayal of Brixton as a violent, crime-ridden area and the characterisation of black people as muggers and rapists that the only possibility of travelling there by public transport late at night was either by a limited night bus service or the very few taxi drivers willing to take the risk.

Alex had no problems about taking his fare to Brixton. As soon as he saw ‘Yes, I'm Homosexual Too‘ emblazoned on the badge Malcolm had pinned to his chest he felt able to acknowledge his own gayness and established an easy rapport about gay life and his his travels to Morocco. With Malcolm as a friendly contact at the Centre Alex went there a week or two later.

Prior to that The Boltons and The Coleherne in Earls Court and the Union Tavern on the Lambeth/Southwark border were the main places he visited but at that time the Union Tavern was restricted to Sunday nights only. Without romanticising the past by suggesting that things were better then than now Alex still experienced his first taste of the gay scene as in some way uplifting and visited it practically every night even although upstairs at the Boltons people met in a furtive atmosphere of secrecy. He was aware that rent boys often hung around in the downstairs bar. He also visited the nearby Catacombs. His visits to the gay scene were tempered somewhat by the need to observe the rule that "Once you stepped out into the big outside world then you had to watch what you were doing."

He was not attracted to the leather, denim and SM scene at the Coleherne or the "...cloney sort of image. Moustaches and all that" though he grew one for his boyfriend Dennis later. He was somewhat bemused at the incongruous set up of leather queens 'mincing around‘ while a woman played tunes on a grand piano as though she was at a tea dance. Sunday night at the Union Tavern in the era of black popular music saw gay skinheads congregating there in the late 1960s:

"Yeah. It was the era of the ska-reggae and the skinheads with the braces and faded denim jeans....with their socks up to here and Ben Sherman shirts. They all used to dance to this ska-reggae music but they were all gay. They were!"

At the tender age of 23 he paid regular visits to a cottage called the ‘Iron Lung‘ round by the boats on Chelsea Embankment near Lotts Road. People would go straight from the Hustler pub on Kings Road to play out the discreetly choreographed movements of cottaging behind the pierced screen enclosure of Victorian cast iron work that shielded the occupants from view in the local Gents. Large queues formed in the ‘Iron Lung‘ until the lock ups were vacated at variable intervals.

"That was enjoyable...in 1964...it really was enjoyable."

The scene at the Gay Centre was something different. With an open door policy the front door in the summer months was literally left open. On balmy summer evenings Alex could see right into the Centre. He had always had an affinity with hippies and freaks living alternative lifestyles and marvelled at the long haired males inside who lounged around in old armchairs. "I didn't want anything posh" was Alex's thoughts on first seeing the inside of the Centre and his attraction to long-haired men secured any future interest in it. He was pleased to see a place that was very relaxed and that catered for young gay people living an alternative lifestyle. A friendly cup of coffee and introductions greeted him on his first visit:

"Yes, I liked the atmosphere. It was infinitely preferable to the straight gay scene because people were more....l mean I liked that element....peopIe were more politicised, there was a message, there was a cause. They were much more my sort of people than the straight gay scene. The straight gay scene was amusing and everything with the polari, I mean people used to go around saying 'Nanty measures? dear’ and ‘Ooh, vada the lallies' and 'Vada the eek'....'Bona Riah, dear‘. That was all very amusing but they weren't very aware. It was much preferable the Gay Centre and I didn't really look back after that. I didn't really want to go to straight gay pubs after that."

"Well, I seem to remember that John Lloyd was on duty and he was very welcoming. He made me a cup of coffee and that and introduced me to a couple of people. Probably Graham Mumford. Oh, and Chris Langan and Lloyd Vanata. I made friends with them I think from the outset...oh yeah, and Rowland and his boyfriend Gary. We hit it off right from the start. Those were the first members at the Centre. I think Mark Carroll probably."

He did not entirely disqualify the ‘straight‘ gay scene. The amusement he derived from Polari the outrageously camp language of the homosexual underground from pre gay liberation days when it was dangerous to be obviously gay in speech or writing stayed in his memory and allowed him to recall days of friendly if closeted social gatherings.

But life wasn't always a carefree weaving in and out of the social round. The episode of the ‘Mad Axe Man‘ showed that the problems of a public presence and an open door policy could attract hostilities as well as provide a friendly social centre for gay people even though the friendliness was dampened by the political animosities that grew to a head in the summer of 1976. Alex reported his feelings of unabated terror as he fled into a back room of the Centre. The fracas began when a '"big, rough-looking" man came into the Centre. His observation that "Oh, your gay" followed by "What's it like being gay?" was given the somewhat condescending reply of "Well, if you want to find out what it's like to be gay sleep with a man." This did not bring out the best in him. He freaked out and went away returning with an axe in his hand. With the battle cry "I'll kill the fucking lot of you" he brandished the axe as though he meant it. He pointed to someone and said "Your're dead!" Alex ran off into the back. "I could visualise him burying the bloody axe in my head."

"He was a very big guy and he looked very, very angry. He pointed to somebody and said ‘You're dead!‘ Bill Thornycroft....I disappeared into the back of the Centre and I didn't really know how I was gong to get out of the Centre, you know, because....I remember....I have this vivid memory of Bill smashing the man over the head with a chair to stop him which was very courageous. I don't know what happened. He went off and I think he was going to get a posse of people to do us all in. The police were called and a number of people were taken down to Brixton police station. I wasn't one of them. I was absolutely petrified."

Alex first encountered politicised gay people through the gay centre:

"I admired a lot of people, the politicised ones. I mean, not everyone was politicised. What became known as the Hierarchy - Alistair (Kerr), Colm (Clifford), Gary (de Vere), Stephen Gee, Tony Smith, Edwin Henshaw - I took to them. l really liked them. I thought they were all interesting people. It was marvellous. Politicised gays were a new thing for me. The political angle."

But problems arose between the 'hierarchy' and those who were less able to clearly articulate their thoughts and feelings. Described derisively by those in the know as 'nerds' they were given a hard time. Also controversies arose over non-gay politics at the GC:

"...I used to enjoy the Wednesday (weekly) meetings...fairly democratic. People could put their grievances...they are aired and discussed. Unfortunately I think the less articulate people got a bashing from the more articulate ones. They shouted them down. Well, I mean, I suppose we did our best with the Wednesday meetings. To try and make it as democratic as possible. Things were sorted out. Price of coffee and all that. It used to be five pence a cup in those days."

"Well, they were more politicised and more articulate, the so-called hierarchy. That was a bit of a shock for me because there were things about....the Irish business. There were posters about that. It was a bit of a shock for me because I felt that....One might argue that the people in Ireland are being oppressed by the British and we could identity with them. Subjugation and all that by the British. I was never really into politics and there were these posters. I felt, Oh I don't know about this. I don't think they should be telling me how to think about the Irish business. Troops out of Ireland and everything. Leaving aside what I feel now about it at the time I felt as thought they were laying this on me. I just ignored it."

"I suppose what you are saying is that the big divide was the less articulate and less politicised ones were there and the more articulate and more politicised whoever they were....not being particularly politicised myself it was quite a new thing...that was where the gulf was I think."

He remembers the gay wrestling group and the controversy surrounding it with a knitting circle set up in opposition to it:

"Yes. I wasn't particularly interested in wrestling. A lot of people were and this guy Don Black came along. He was gay and said that he was interested in starting a wrestling group and asked if any other people were interested. A lot of people expressed an interest. But there was that position from some people...they thought it was a very macho thing, wrestling, and they opposed it. I was sort of indifferent really. I didn't particularly oppose it. We had a lot of meetings about it. It was quite democratic and he was allowed to have his wrestling."

The bitter disputes around the question of bisexuals using the gay centre, labelled by the more militant gay liberationists as 'baby bios' or semi-breeders, dragged on for many months but what annoyed Alex more than this was the use of the Centre by straight (bisexual?) couples for sexual purposes:

"....I mean, they were labelled baby bios and people felt that they shouldn't really be allowed in the Centre. My feeling was that if you are bisexual then part of you is gay. So why not? I think I actually said to two people once....they clearly weren't bisexual. They were a straight couple who came in and were just using the disco downstairs....the mattresses that were around for people to sit on. They were just snogging away and I felt they've got the big wide world outside. I think I said to them ‘Did you know this is a gay centre?‘ It wasn't a question of being down on straights. It was a question of they were using our little space. The only little space we had in the world. Yet they had the big wide world outside. That was my feeling but bisexuals were put down by certain people around. I thought it was valid to be bisexual. lt was one of those things. People are bisexual. They have got a gay and a straight side to them. So, yes l recall all that."

The catchment area for the Gay Centre was mainly South London with one or two visitors from North London and further afield. In terms of using the Gay Centre Alex gave up on the commercial gay scene and was captivated by the people who went there:

"No. I really took to the Gay Centre. In actual fact l was going to mention that. In '72 I was living in Sydenham and l was so enamoured with the Gay Centre....l wasn't actually working as a taxi driver now I recall. l was chauffeuring. I used to do my chauffeuring and then any time after ten or eleven and l used to get to the Gay Centre and stay ‘till two knowing that I had to be up at six o'clock in the morning. So I literally got four hours sleep because I was so enamoured with the place. I subsequently moved in. I met someone in the Gay Centre, Dennis (Simmonds), and he had a squat off South Lambeth Road. But then he moved to a squat in the gay community in the Mayall Road and I moved in with them. I really took to it like a duck to water. I was spending all my time at the Centre when I wasn‘t working. So I really had to be in the area."

"Lloyd Vanata and Chris Langan, my two buddies, used to stay late. Graham (Mumford)l think. I often used to walk home with Graham to South Lambeth Road. They were the ones I remember mostly. Mark Carroll of course. Some people were working and had to get up. Then of course I moved into the Residences (St. George's). I moved into the Residences before I moved into the squat with Dennis...."

He recalls Pearl's shebeen run by a black woman specifically for black gay men in an area with little social facilities for them. White gay friends were also welcome:

"Malcolm (Greatbanks) used to drink there. Possibly John (Lloyd). I remember Big Jack, a West Indian guy, who sadly died. He used to go there and a lot of black guys obviously. Presumably they were closeted. But a lot of people from the gay community used to go there. I remember Stephen Gee used to go there. I saw him there once or twice."

Alex remembers the real ‘characters' around the gay centre. There were the 'scatty queens‘ who flounced in and out of the centre. But two people in particular stick out in his mind. One with the nickname ‘Mercy Dash‘ (Ken Fuller) suggesting a fussy insistence on 'taking charge' and immediate action and the other named ‘Collis Browne‘ (David Fuller) denoting an addiction to drinking a particular brand of morphine-based cough mixture. He died later in France after losing a leg in a car accident.

"But the infamous Ken Fuller....this character walked into the Centre one night and he said that he was the caretaker of NACRO which is the National Association for the Care and Resettlement of Offenders in Milkwood Road....He was in charge of the hostel there. He didn't actually say he was gay but he came in and we presumed he was gay. l think it turned out later that he wasn‘t the caretaker but he was an ex-con who was in the hostel for ex offenders. He made himself busy in the Centre. He was one of those people who wanted to get really involved with a lot of duties behind the counter. I'd moved in to the Residences (St. George's) with Dennis. John Thornton was living there with Twiggy. Do you remember Twiggy? A very skinny young guy. We lived there....it was a bit of a difficult time. We weren't really compatible. So there was Dennis and l and Twiggy and John Thornton. Ken Fuller had to disappear to go to Switzerland for some reason. He was a bit of a slippery character. There were some unexplained things. Anyway he had to leave rather hurriedly to go to Switzerland and for £50 he sold the rights to the squat to John Thornton. l never had any say in the matter. l mean, l was living there in a squat but the rights to the place were sold on to someone else."

"Well l think Ken was bisexual. That's undeniable. He used to take a shine to different young guys that came in to the centre. I don't know where she (Marie - described by Alex as a 'funny little Geordie girl') came from. She just appeared like a lot of these people used to float in and he struck up a relationship with her. Sunday night a lot of people used the place. It was open and it was somewhere to go. You could get a cup of coffee and some company. The discos were good. They didn't care that they weren't l gay. I suppose we didn't really mind. I mean, we thought they were gay. So we got that sort of transient population."

Alex met his long-time dearly beloved Dennis at the gay centre. Their relationship lasted for over twenty years:

" My Dennis? Oh yeah, this is the big thing. This is how the Centre functioned so well for me. l came in there and it was a social centre for me. So l spent a lot of time there and....l was 35 at the time and there was this young guy there who was 20 who was holding hands with another that was his first boyfriend. He was called Duarte? He was a Portuguese guy. They had met on one of the marches. So I thought this is really lovely. l mean, l thought l'm over the hill at 35, one of the elder statesmen of the gay world looking benignly at these two and I thought, ‘Oh lovely. They're holding hands and they're 20. I wish I'd enjoyed that but never mind. There's still time even though l am 35.‘

I learned later that it never really happened, his relationship with Duarte. Duarte sort of ended it. He said he didn't really feel as though it was going to happen. Obviously that was traumatic for Dennis and we got talking. I didn't realise he was interested in me. l was very friendly with Graham (Mumford) and Dennis was quite friendly with Graham because they used to go out together and

smoke. A lot of their life revolved around scoring dope and smoking it as you know. One day Graham said to me look....l'd already spoken to Dennis but l didn't have an inkling he was interested in me at all....Graham said, look we're going back for a smoke to my place in South Lambeth Road, do you want to come. I said, well l don't really smoke you know. He said, well Dennis is coming, very pointedly. So I said, Oh well perhaps I'll come along. He'd said it to Den because l think I'd intimated that I was quite attracted to Den. The rest is sort of history.

We got to know each other and got it together. Yes, it functioned so well for me because I met someone I would never have met in any other context. He didn't do the straight gay scene. I think he'd been to the Union a couple of times but I suppose it's true to say that we're both quite shy. I mean the chances of meeting in any other context were very, very low. So I started having a relationship with him and it was wonderful, absolutely wonderful. I have got no regrets whatsoever. So that's something really marvellous that came out of the Centre for me."

Alex was aware of the people living together in the Railton Road and Mayall Road gay squats but had little interaction with them apart from at the centre. On the occasion when he was aware of critical comments on he and Dennis' being a couple and 'monogamous' his answer was straight forward and practical without the baggage of ideological purity:

"My view is you can have a relationship and provided both parties agree, you can have a stable relationship, but you can have sex and little flings with people outside of the relationship. The fact that you choose to live together, even if it is aping married couples, what's wrong with that?"

Occasionally Alex visited the Oval House Theatre, mostly for the cafe, but he remembers seeing Stephen Gee playing the piano in a Brixton Faeries production and was 'knocked out' by their play 'Gents' about cottaging and 'Minehead Revisited: The Warts That Dared To Speak Their Name' about the Jeremy Thorpe trial.

After the squat at nineteen St. George's Terrace was 'sold' Alex was left with the strangest of co-squatters:

".....We were left with John Thornton and Twiggy. l mean, John Thornton was another strange character. He was the straightest of straight gays you could ever meet. He worked in a meat packing factory in Croydon or somewhere. Oh, London Transport. Packing meat or packing food for their canteens. Because he had a day job he kept conventional hours. He used to crash out at midnight l suppose but he was one of those people who could fall asleep with the radio blaring. ln fact it helped him to stay asleep. We had to tell him that he was keeping us awake. This bloody radio on all through the night. Quite bizarre because it threw people together from such totally different backgrounds who would never have lived together out of choice. But because of the availability of gay accommodation if you like, mainly squats, you just had to take what you could find. So we were thrown together with this bizarre couple one who was the straightest of straight gays you could ever meet, not very politicised or aware. ..."

Alex recalled two more people who particularly stood out in his memory, Rowland and Graham Mumford:

" Well, you know he (Rowland) started off as a delivery driver for R White's the lemonade people and he graduated to become a delivery driver for Currys and then he went on to become a manager for one of the big stores. Comet. He's was head hunted. He'd done very well for himself. He started off as being a van delivery driver and graduated to being a manager, a shop manager. He's a bit of a trouble shooter. They send him to any of the shops where the takings are down. So he's got a good job. Well paid with bonuses and a company car and all that. His gay life....I mean, he couldn't come out. You know, it would be over simplifying it to say that anybody can come out."

"Yeah, getting on to Graham. Sadly Graham died last November, the 7th November 1996, of a heart attack. He was one of the catches at the Centre that Den and l made friends with. Probably the best friend of the lot, of all the people who ever went to the Centre. Cinema projectionist. He did work at the Ritzy at one time, for a short time. NATKE, the union projectionists belonged to, were not very good at fighting for rights. Cinema projectionists were grossly underpaid. That was the only trade Graham knew. He came from Aston, Birmingham. He came to London probably because he thought the streets were paved with gold. He got to know a few people and took to it. Yeah, he worked at different cinemas. The Ritzy and what is now the Fridge which used to be an ABC. For ten years he worked at the Screen on the Green at lslington. The Screen on the Hill I think he worked at. Part of the same group in Hampstead. So he did move about a bit but he did settle at the Screen on the Green for twelve years from about '84 to '96. Oh yeah, he did have one little stint as a security guard for about six weeks but he didn't like it. He went back to being a cinema projectionist. That was his life. That was the only thing he knew and that's what he did. He was very much one for the scene. He used to go to the Market Tavern, the Vauxhall and the Elephant and Castle."

Alex social life became focused on the Centre so much so that he spent most of his time there when he wasn't working often staying until early morning which left him with only a few hours sleep before getting up for work. After the Centre closed he went back to visiting his old gay haunts again ‘to fill the void’ mostly the Two Brewers, The Royal Vauxhall Tavern and the Elephant & Castle. He made a lot of friends through the Centre including the dances organised from there at Lambeth Town Hall. The social setting of the Centre and the ease with which gay people could greet each other on the streets and speak to each other did not alter the fact that as a cab driver it was still impossible for Alex to come out in his profession. He was able to relate to the gay community centre and other gay people but the cab drivers he saw on the road and regularly met at tea places would not have tolerated his gay identity:

"To be frank I was frightened. In my world I couldn’t come out as a taxi driver. I mean they'd just be unmerciful if I was to come out. So I had to stay in the closet. If I had been brave I could (have come out) but I wasn’t that brave. I was afraid quite often that people would discover that I was gay.... "

Though mercifully this did not stop Alex from braving those first steps into the gay centre and discovering the adventure of living and loving a more open and generous life than he had ever experienced or thought possible.

DENNIS SIMMONDS

INTERVIEWED BY IAN TOWNSON - 14/05/1997

I remember the wrestling group, yes. I sort of saw the Sissy as the hero, if there is one, of the gay movement and the enemy, the bad guy, as being the macho gay. I was shocked when I actually found out they were handing out copies of Zipper. I was really, really shocked. The discrepancy between that and their fucking ideals - I was shocked that the people who were espousing the Sissy as the hero and then finding copies of Zipper with these great big hunky, over the top, overloaded, over everything....men

L-R: Alex and Dennis

Dennis Simmonds was born in 1956 and grew up on Loughborough council estate in Brixton. He had no brothers or sisters and attended Loughborough primary school, later Tulse Hill Comprehensive school for boys. Towards the end of his secondary school education he spent much of his time truanting. He would get 'signed in' on the school register and bunk off for the rest of the day:

"....l learned the word ‘queer’ and me and l stopped. That was when l was 14. There was a big kind of moment of....'Oh, god!' and there was a lot of personal problems related to that and...the effect it had was l refused to be educated anymore so l would just not go to school. From that point on l stopped being educated. But it was CSE level. l was there until 16 but l stopped going at 14."

His dad worked as a van removal man, later a property master in the film industry. His mother, besides being an unpaid housewife and household carer, worked in "everyday kind of jobs like working in Sainsbury's to get money."

Politics and religion played no part in his family when he was growing up:

"No political awareness at all. l always had my own spiritual beliefs which were mine from dot and l distinguish them from religion. Religion again was frowned upon because my mother had an Irish catholic background and she had experienced a lot of abuse through that system. So she was determined to ensure that they wouldn't get me in their clutches. She was anti catholic church with a passion and so anti-religion. So there was no religious or political awareness in the family of any kind. Yet I had my own spiritual voice."

Dennis was aware of being 'different' at a very early age but did not have the 'language' to make sense of the quality that set him apart from others. It was only when he heard the word 'queer' as a thirteen or fourteen year old at Tulse Hill Comprehensive that awareness of his gay identity had been triggered. He had fleeting memories of the intervention of radical drag queens at his school:

"Yeah, if my memory serves me right, I think it was the sixth form conference room used to be the setting for the sixth form debate. Different debating societies or groups would be interested so they would be invited along and I was told that one of them being invited along that evening was people from Gay Liberation from South London. I presume that was related to Julian (Hows), that he had organised that and got that going. I didn't know of anyone else who was so frighteningly over the top 'out'. I presume he got that going but as I was a fourth year I wouldn't have had access to it."

While still living at home he found out about the South London Gay Community Centre via the local press which had run an article on the Centre's Gay Liberation Front candidates in the 1974 general and local elections:

"I'd seen pictures of Alistair (Kerr) and Malcolm (Greatbanks) in the South London Press standing for some political office. The address of the Gay Centre, Railton Road, was there. There was a photo of them outside it. So that's how I placed it....I popped in. I must have been about seventeen which was about 1974..."

He eventually plucked up courage to enter and likened discovering the Centre to a 'flood of light' that dispelled the dark gloom of the closet:

"When the pressure was really difficult enough, great enough, l was forced out and I dared to look at this place to see what it was like. I took a walk up Railton Road to have a look but I couldn't bring myself to go in. That was on Saturday evenings when the need to be with other people, to be with other males, was felt to be very pressing. So I kind of scouted round and checked it out and promised I would go in and all that. Then one Saturday evening I pushed myself through the front door. On my first visit I met Andreas (Demetriou), a very predatory Julian (laughter) and John (Lloyd) who claims he only ever had long hair but I distinctly remember him having hair only down to here (shoulder length). So it was short. Malcolm Greatbanks was also there."

His parents moved away from the run down council estate in London to Farnborough from where he made weekend trips to London:

"I just popped into the Gay Centre every now and again. I began going on marches. There was an early march about 1975 and I'd read about that in Gay News....It wasn't until my actual return to London, I think I was about 20, that I began to go on a really regular basis. Then I moved back into a squatting community in Vauxhall. They had been there for a year or two. One had just become available and I just accidentally happened to bump into these people and discover them. There was a house at the back of us which had Bernie and a couple of people there and Jamie? with the big beard and another guy. I knew John Lloyd lived on South Lambeth Road (Tradescant Road - all gay men).

Dennis eventually moved to a gay squat at St George's Residences in June '76 with Alex Beyer, his partner for over 20 years, just as the Centre was winding down:

"We lived with Ken Fuller. Crazy Ken and his keys. What happened for me was I was squatting in Vauxhall and then I met Al. We began to spend time together and we kind of got together and he was living in one of the Residences. In the place that Ken Fuller had squatted. Ken had let him have a room. l had got hepatitis and became very unwell at the end of that summer. The squat in Vauxhall closed down and so I moved then into number 19 St. George's Residences with Al and Ken. Then mad Marie, Ken's girlfriend, turned up (see Alex Beyer's interview for an account about Ken and Marie)"

"There was Chris Langan and Lloyd Vanata living in number three. There was another squat somewhere....I even remember I think earlier Aunty Alice (Alistair Kerr) may even have lived over the Centre at some point. I remember them coming out of there. So there were in the Residences probably about 3 gay squats which mushroomed later to about perhaps 8. But at that time there were 3. There was also the one on the other side of the Residences (Railton Road?) which had Michael Cotton and his boyfriend Stefan (living there) who was also Alex's boyfriend before I met him. Michael Cotton was in the wrestling group and had something to do with the Battersea Arts Centre."

He highlighted the problem of heterosexuality and bisexuality at the centre and, as it was nearing closure, the lack of a firm policy of who should use the centre after the departure of those who were principally involved in organising and running it:

"l mean, it was a Gay Centre and l remember an issue of the heterosexual couple downstairs on the mattresses snogging on Saturday night just before the disco was about to start at about 9 or 10pm or something. People protested that they shouldn't be allowed in there because it wasn't right....People going down (into the basement) and looking at them like specimens. They were doing it on the mattress. Why are they doing it here? l also felt offended. I also felt at the time, you know, that they oughtn't to be allowed in."

"...the point was they had drifted in off the street. l swear some people were in the Gay Centre because they couldn't sit in the bus shelter all night and snog. lt was easier to sit in the Gay Centre and snog with their girlfriend than in the bus shelter. So they drifted in because it was an open door. There was nothing saying ‘not admitted‘. So all sorts of people were in there for all sorts of reasons. The lost, the lonely and you know,..."

"People who identified as gay also had a bisexual side to them. Having girlfriends appearing. This was sort of challenging the idea of true blue. Gay through and through. As I understand it that hadn't really been addressed and resolved in a way that did justice to people who identified themselves as gay yet at the same time can have a bisexual side. All that stuff hadn't been worked out so when these girlfriends started appearing it brought a lot of stuff up for people. They were appearing and people like Graham (Mumford) had a girlfriend and Ken had this girlfriend. Then other people that walked by brought girlfriends along. The division between the gay-identified bisexual people and the people that identified totally as gay just grew and grew and grew and then exploded. So Marie was just one of these

people who just turned up. I mean, at the time I used to feel like a bit of a snob. I used to think ‘where have these people come from. Who threw them up?’ It was as if they had been dragged off the street from somewhere. Marie was one of those people."

"Again another thing I was thinking of....l don't think the concept of being ‘gay friendly‘ was as well rooted then as it is now. There was still this kind of either/or. You're in or you're out. You're straight or you're gay. There was a lot of that black and white thinking going on in people's divisions. I'm sure many gay people, as I did, had straight friends but the concept of ‘gay friendly‘ with lots of room....and the possibility that gay friendly people could be people that are cheerleaders and supportive and friends, people on the journey, that wasn't really established then. So when these people floated in, these girlfriends, it caused a lot of difficulties."

In keeping with the spirit of the times there was a considerable culture of drug consumption among gay people around the squats and at the Gay Centre. This mostly consisted of smoking dope but also hard drugs were involved. Dennis gave his views on the appearance of heroin on the scene and the origins of his addiction to the drug:

"I think heroin use came about when more of the criminal element sub-culture part of the gay world moved in. People that were possibly professional thieves and ponces and various types. They brought the heroin habit with them. The understanding that people took heroin. Up until then, as you said, it had been dope and perhaps hallucinogenics. They were sort of expressive and exploratory and possibly even artistic. They had value and all the rest of it. That was partly true and part of the overall experience."

"I think the more criminal element that started to move in....they were much more the sophisticated criminal gay underworld from Central London, the West End. When they came along one or two people from that group came along with heroin use and began to suggest that it was all part of the broader picture. You know, like a bit of joint, someone took acid or something and now there is this. There is heroin and morphine. So that came along just as the Centre had finished. It had actually finished. Actually l hadn't thought about this before but l think it was significant that it came along when the Centre had finished because it had closed, just completely closed, just fucked up and dwindled. Dwindled and then it just went out."

"The thing is, as l see it, the gay liberation vision, the ideology and the methods used by Alistair (Kerr) and all the rest of it, hadn't been able to embrace and bring with it in its vision all those that were the ‘nerds’, the ‘baby bios‘. Because their voice had been completely disrespected and oppressed, shouted down and denied, they then thought that they could take over and run a so-called Gay Centre as good as the (departed) 'hierarchy' without the spirit, the vision of gay liberation. Without that vision there was no real Gay Centre to last very long. lt was when that went that heroin moved in. So it is significant."

Further thoughts on hard drugs and the demise of the gay liberation ethos:

"Hard drugs moved in when the actual vision of gay liberation moved out of the Centre. Then it was where did people go from here. People moved up the road to those squats....159 (Railton Road) and all that. They carried on a sort of daring and very playful gender fucking type stuff. They carried that on. The vision, the spiritual side of what the Centre was about, if you like, didn't exist any longer for the other people. Drugs became another option. They seemed attractive and so hard drugs were then introduced. They weren't previously. l never knew anybody that was using heroin before then. As the Centre was gone a whole collective vision for me had fallen away and something happened. l think for many people....what would replace it? There was this other lifestyle, gay lifestyle, that people would tell me about that involved the West End. That involved Earls Court and hob knobbing with rich queens and ripping them off. l never knew about that. lt wasn't really me anyway. But there was a whole sub-culture rent scene. lt started to spring up. There is a sort of illusion of camaraderie in the druggy sub-culture. But I say it is an illusion because it doesn't go very far beyond competing for the punter. Competing for the same punter, the same drug."

Dennis lived in St. George's Residences for about a year before moving to a another squat at 140 Mayall Road with Alex. The place had already been occupied by Edwin Henshaw. Despite separating from the drug culture his heroin habit still persisted:

"I continually went back to the same thing. lt was a funny thing because we were kind of like....it was....Edwin was part of that other group (hierarchy/gay liberation) and here l was this mad junkie with a lot of awareness but definitely becoming increasingly unwell.

"A foot in each camp. The sub-culture. Hard sell. If it moves sell it and if it doesn't sell it around the corner. Then there was what l saw as the original (gay liberation) inspiration for why I moved there in the first place. But not really feeling as though l belonged there. The squat really never came together as a groovy sort of Gay Liberation South London squat because l was into drugs and l didn't really cooperate and do things. We backed on to the gardens (communal gardens) but by then l felt really very alienated from everybody but also from the 159 lot because there was a....l had become seedy. l was very ill psychologically. l'd had another lot of hepatitis....l had my second lot in two years so yeah, l was getting quite ill."

He lived in this squat for about two and a half years before moving with Alex to a council flat with fears about moving out from the relative sociability of having other gay people in the area to relate to:

"....l got one of those council flats that had come up. lt was very frightening because I hadn't the sense of sheltering in this community that had lots of gay people. There were many gay faces on the street for there to be many gay people to be acquainted to if only in afternoon and morning times. l didn't realise how much of a sense of safety that created and to be moving out of that and to be going away to a council estate way down on Wandsworth Road or whatever. It was very scary. l didn't realise there was....even though it was all fragmented....at least for a time there was the feeling of a sheltered haven. I wasn't totally alone at the mercy of the straight world and this illness."

On the positive value of squatting and how unemployment was less of a burden than it is now because welfare benefits were 'sufficient' to live on:

"l mean l think that the squatting was part of....it was like an alternative....for me it was like an alternative to everything. Alternative diet to my parents, alternative beliefs to my parents, alternative sexuality to my parents to....try my own form of expression in the world. That was what Aunty Alice (Alistair Kerr) personified for me and people like that....and the Gay Centre personified. Enough freedom to express that individuality. May be a lot was able to happen because people didn't have to work. lt was alright to get by. l could get by. People could get by on unemployment benefit and grants. There were grants. It was there to be milked. Clothing grants and furniture grants and all that. Every twelve months l was writing off for my new linoleum grant, you know....it was about my idealism."

"lt wasn't just about being gay....being gay is much broader anyway. It is about many, many things apart from just sex. That's all part of the nine to five job thing isn't it. Get you in quick, get you in deep, get you in so a far up to your neck that you can't even fucking think for yourself. That's part of the deal isn't it. The machine just sucks you in and it's hard to get out. That's the way they like it."

Dennis spoke further about memorable people and events:

"Yeah, the actual event of the take over. l just saw the front page of Gay News or whatever it was called with Ken Fuller and Marie and Graham Mumford and Skippy who was his girlfriend. A local girl from Brixton. Mark Carroll was there also. That and the announcement that there had been a 'coup' at the Centre (explain) and that it had been taken over by these people. That sticks in my mind."

"Things like the Captain Morgan's Rum campaign (explain). Going around South London with a bag full of these stickers and sticking them on bus stops and adverts and all those things."

"Kay throwing her weight around. Going off to....Again things that I thought were unfair like, people would go off to a dance or something in West London or North London or somewhere and insist on about ten of us getting onto a carriage (tube train) and breaking up into pairs and sort of snogging in front of a single straight couple as an act. lt was a real kind of 'freak ‘em out thing'. I used to think that these poor individuals...these straight people were being freaked out. Then there would be a straight couple at the bus stop on their way home from somewhere. There would be three guys standing in a row all doing the same deep snogging. Goodnight snogging to freak them out. Those kind of things I remember. All the things that were powerful, exciting and what have you."

His observations on the Gay Wrestling Group:

"I remember the wrestling group, yes. I sort of saw the Sissy as the hero, if there is one, of the gay movement and the enemy, the bad guy, as being the macho gay. I was shocked when I actually found out they were handing out copies of Zipper (explain). I was really, really shocked. The discrepancy between that and their fucking ideals - I was shocked that the people who were espousing the Sissy as the hero and then finding copies of Zipper with these great big hunky, over the top, overloaded, over everything....men"

He was attacked for his monogamous relationship with Alex and criticised the authoritarian methods used by Gay Liberationists who 'encouraged' couple busting (explain) and shamed those who were felt to be aping 'straight', heterosexual relationships:

"I think Alex and I got some of that. Some of that married couple syndrome. Having to apologise to people (I met) in the market (Brixton). The methods used were as authoritarian and oppressive and the bid for freedom (by Gay Liberationists) was often at the expense of other people's freedom. It was justified because it this was Gay Liberation South London.

lt was just as authoritarian and just as disrespectful of the totality of all people and all things and everything having its place."

"Some of the homophobic, oppressive, anti-gay stuff that was in the culture we had grown up in was being recycled and re-fed to other gay people because of individuals personal hang ups which most people hadn't dealt with. lt was re-wounding and re-infecting gay people in the community with the same culturally oppressive attitudes and shit thus leaving people wounded again instead of empowered. So we ended up being ‘the married couple"

"l would see Colm (Clifford) and it would be like seeing the neighbour you didn't want to see coming down the road. He'd say "How are you" and I'd say "We're still together". Then l used to start apologising and then....this is the fucking shit you get. He would then tap you on the arm and say "That's okay". lt's like someone else always tells you who it is you can be and when you can be it and will define it for you. Then when it's not okay they'll tell you. But when it's been corrected according to their whim there into it being okay. After they had put all this forward about married couples."

His views on interaction with the wider 'straight' community:

"There were places that were sympathetic like the housing place up the road (Brixton Housing Co-operative), Maureen Boyle (Brixton Advice Centre). There were various people like that and Veggie restaurants and places that were kind of...alternative ways of living and gayness was seen as it is, another one of those forms of individualism. An expression of how it is done by us; not by you or by them but by us. So there were people like the Veggie restaurants that were about. The Grain Barn place (Bangladesh food co-op?). A few people who worked for Advice Centres and that kind of stuff."

"There was very little contact with the black community. Very little as I remember. Apart from Pearl's (explain) l think the political thing between blacks and gays was too much for black people....they seemed to be claiming that being gay was weakening their blackness. Gayness was diluting blackness, black consciousness. The strength of gayness is that it cuts across everything. That's its strength. lt's a bridge between everything. So it breaks all of those things up. That's its great strength in my opinion. So the black community, the political people at the Black Bookshop, they were always intimidating. l had some hostile stuff from them"

On the observation that some black radicals viewed homosexuality as a white man's disease and that black gays were a traitor to their race for not producing black children:

"lt's just an outgrowth of catholicism and all the rest of that nonsense. Yeah, that's right. But the commercial places like Pearl‘s said something different which is an interesting point. When people get away from the ideals...a lot of that conceptualising was dropped. People, human beings, gays make connections which is gay strength way beyond all the concepts. The black guys....we went down there and made contact. No doubt some more than others."

On the observation that some people around the Gay Centre engaged in mysticism, the Tarot and the occult he gave his views on spiritual traditions:

"From my own point of view l actually believe that gayness is a spiritual tradition. One that has been buried for hundreds and hundreds and thousands of years possibly. lt‘s a new path to understanding. lt‘s the path between us and everywhere. There are many mystical schools that have begrudgingly made room for gayness. Yet in fact it is a path in itself. My own personal belief is that the shamans in our culture....we are a people without a stage. There is something in the quality of gay energy that can be in some people. It's something odd. It is shaped by an experience that you listen....that you find out your own truth. Because no other fucker around you will confirm the truth. Your own fucking truth. A lot of straight people just rely on their senses and information that is given to them directly. Many gay people from my understanding, myself included, have had to rely on other sources. Have had to develop other senses that came out of the experience of having no other fucker around you, around me, that was mirroring my essence. Mirroring me. That translates into a spiritual perspective.

Brixton Gay Community, Derek Cohen

- August 2020

There was an empty house suitable for squatting down on Railton Road in Brixton. It wasn’t joined to the rest of the gay community, but there was only one house in between. So, like alternative estate agents, they met me down there to look over 145 Railton Road. They all had experience of squatting and doing up abandoned houses and could help me assess whether it was habitable. The roof and floorboards were sound, but many of the windows were missing and there was no electricity or gas around the house, though there were meters in the cellar.

Derek Cohen late 1970s

Derek and Hans Klabbers enjoying a sunny day in the communal garden

How I came to know the BGC men

I first came across the Brixton Gay Community around 1973 when I occasionally visited the Brixton Gay Centre on my weekly trips up to London from Southampton for weekly in-service training – I was a residential social worker. After the training I’d sometimes go down there, though in my timid barely come-out state I found the flamboyant gender-fuck dressing of some quite intimidating. But everyone was welcoming and it was a start. On the way back to the hostel where I worked and lived, I’d buy a copy of Gay News which I’d hide under my bed. It would be another couple of years until I actually “came out”.

In the late seventies, well and truly “out and proud”, I started attending an informal gay meet up at The Oval House Theatre opposite the Oval cricket ground in South London. This was held every Sunday afternoon.

Many of the guys at the Oval House lived in South London, and some I’d already come across at the Brixton Gay Centre. But others came from further afield – I was living off South End Green near Hampstead Heath in London at the time and the Sunday afternoon was, I suppose, the closest there was to a non-commercial gay community meeting place.

It was very friendly and relaxed. Much of the time we sat around drinking coffee, eating and chatting. But there were practical workshops put on by various guys. There was movement and dance, and massage. And some of the men were part of something called Homosexual Posters (Colm Clifford and Ian Townson), which produced agitprop (there’s a word from the past) at the nearby Union Place community resource centre. In the early eighties I worked with some of them to produce a couple of Gay Men’s Diaries for 1983 and 1984.

Why I moved there

In 1978 I started sharing a flat in Hampstead Heath with a straight guy - Patrick. It was at the top of a house owned by Sally, a school chum of my friend Cordelia. It was for two people and Cordelia said Patrick, a friend from her work, was looking for somewhere to live as well. And as I needed to move from where I was living (my big “fucking queer” badges were too much for the owner of the place I was living in) I agreed to both the flat and sharing it with Patrick.

I’ve never been one for outdoor cruising, so I never took advantage of the private gate from the house’s back garden gate which opened directly onto Hampstead Heath and its gay cruising grounds.

Patrick and I got on fine for a year or so. I had my own bedroom where I often had sex, either with friends or the occasional “straight” man from the pub I frequented at the bottom of the street.

But one day Patrick told me “You know I can’t take all this sex you’re having seriously.” I was shocked and upset at the homophobia that emerged.

The next Sunday I discussed it with my friends at the Oval House and they said I needed to move. There was an empty house suitable for squatting down on Railton Road in Brixton. It wasn’t joined to the rest of the gay community, but there was only one house in between.

So, like alternative estate agents, they met me down there to look over 145 Railton Road. They all had experience of squatting and doing up abandoned houses and could help me assess whether it was habitable.

The roof and floorboards were sound, but many of the windows were missing and there was no electricity or gas around the house, though there were meters in the cellar.

Finding windows was easy. There was some rehab going on in the neighbouring streets and the skips contained suitable windows. The windows and frames for the houses seemed to have been mass produced. When you put in a window frame from the skip the screw and nail holes in the frames lined up perfectly with the holes in the walls.

If the glass was broken I already knew how to glaze windows from my residential social work days where residents were often having tantrums and throwing things through the windows.

Sorting out the electricity and gas was a bit harder as I had no plumbing skills, and my electrical skills in the past had regularly resulted in nasty shocks. But friends and squatter neighbours were on hand always willing to help.

One showed me how to solder copper tubing into the lead inbound gas pipe and how to plumb the gas into the kitchen, and I think, a gas fire. The plumbing skills were handy for piping water to a salvaged kitchen sink (which doubled as a washbasin) and the toilet. There was no bath and so I used the bath in other people’s houses.

Another helped me install an electrical ring main around the house so we had lighting and power sockets. Skips were always full of useful stuff, and sheets of wood and wall studs were soon fashioned into a kitchen worktop. I’m afraid my experiences fitting a house out from skips has left me with a life-long obsession for never throwing away today something that might be useful in the future.

Some of the doors were missing, noticeably on the (only) ground floor toilet and, being radical people, none was fitted. I shared the house initially with a Dutch work colleague – Hans (Klabbers) – who I was having sex with and who wanted to move from his parents’ home. Soon after two other men joined us. Colm (Clifford), a veteran Brixton squatter, moved in after one of the frequent bust-ups that occurred in the various gay squats, and an Australian, Paul (Coyle), joined us around the same time. Colm and I did work on Homosexual Posters together and there were sometimes planning meetings at 145 if not Union Place where Colm worked. Colm and I had sex on occasions while we lived together. He was from Ireland and was very sensitive to the British oppression of the Irish. However my Jewish background meant that I was the only Brit who he would let fuck him, he claimed. It was a time when you had sex with someone because it was fun and you felt like it; not because it meant anything significant.

The Hans crisis

My friend Cordelia went to live in Japan for two years and in 1979 I went to stay in Tokyo and Kyoto for four weeks to see her and explore the country. On my return it wasn’t quite folded arms and rolling pins on the doorstep but not far off. Colm and Paul were outraged. Colm had been hunting around the house looking for some fresh porn and had found some straight porn under Hans’ bed. This was a gay squat and a straight man didn’t have a place there. Hans wasn’t apologetic and said he’d always had an interest in women as well as men. This was a time when “bisexual” was usually equated with “closeted”. Hans had to move out and, after much discussion and heart searching, I decided to move out as well and we found another abandoned house on Mayall Road which we occupied. This one was in much better condition and had running water, gas and electricity. My mother in Manchester bemoaned the move, saying I should find somewhere proper to live. I replied that I was on the way up, as this one had a bath.

DON MILLIGAN

INTERVIEWED BY IAN TOWNSON 04/04/1996

There was the idea of having a private space and then having a wider access to neighbours. To have a certain kind of neighbourliness. But then of course the neighbourllness was always restricted really. I remember considerable tensions between different households. I was never there during the period when everybody appeared to get on or there were open, neighbourly relations between everybody. There didn't seem to be to me.

Don Milligan in the 1970s.

Student radical, political activist, communist

Dr. Don Milligan today still committed to fighting for a communist future in his book The Embrace of Capital

IT - When were you born?

DM - I was born in 1945. The fourth of July. American Independence Day.

IT - Where was that?

DM - That was In Kilburn North West London. I was born and brought up there until I was 18 when I moved to Leeds. I moved to Leeds with my girlfriend Sandra who I had met in the Young Communist League in 1960. I lived in Leeds until 1969 and then I went to Lancaster as you will remember. I stayed in Lancaster until 1973 and then I moved to Bradford.

IT - Just going back a little bit. At that time you weren't at University were you?