Alastair Kerr

Revamped interview by Ian Townson from the Peter Bradley 1980 interview

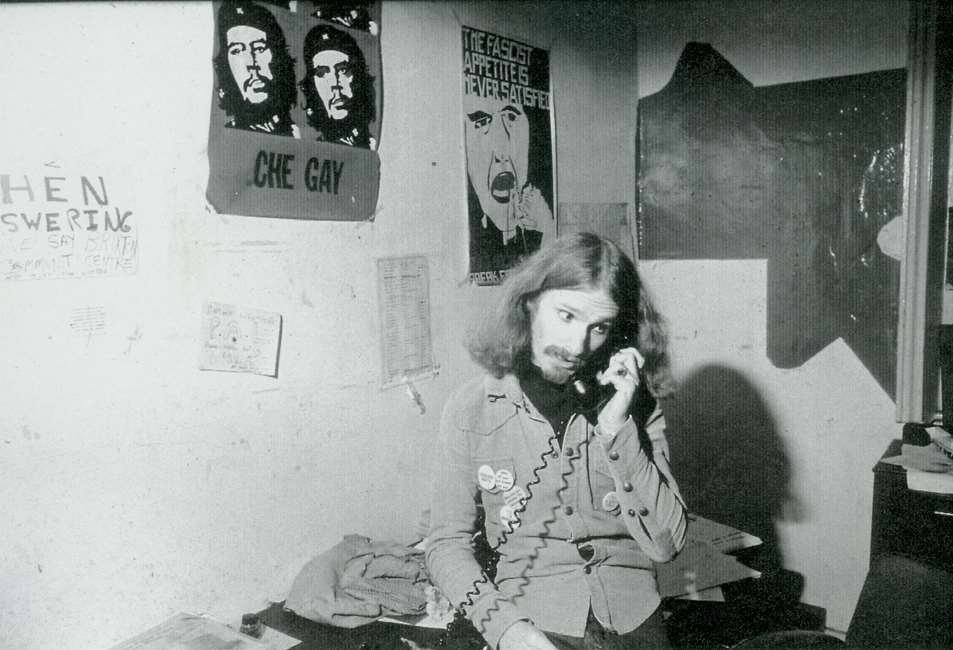

Answering an enquiry at the South London Gay Community Centre (1975)

Alastair Kerr was born in 1946 in Glasgow but spent most of his life living in England. When he was just a year or two old the family moved first to Lytham St. Annes for about ten or eleven years then to Durham where he did all of his secondary schooling at a grammar school. After finishing his A levels and an MA at the university he spent 'a few years' at the art school. He finished there in about 1970 and headed south to Brighton for a teacher training course where he came into contact with the gay liberation group. This first contact with gay liberationists meant that he was able to come out completely.

He came up to London and lived in a house with straight people on Brixton Hill from about 1973. He took up with one or two boyfriends and had a lover for about eighteen months. In July 1974 he left him in order to live above the South London Gay Community Centre where he became its unofficial caretaker. All the time he had been in London he worked at the London College of Printing in Elephant and Castle (now the University of the Arts London’s London College of Communication) teaching the history of art and design to graphic design students.

His father, who he never got on with, retired from a successful career in the Ministry of Agriculture. His mother died when he was about eleven years old and his father remarried in 1965 or 1966. He got on very well with his mother but neither he nor his brothers liked their stepmother. Both brothers seemed to take it in their stride that he was gay and the younger one had gay friends though in retrospect he felt his brothers, especially the older one, were the household "male chauvinist pigs. I mean, macho as it were."

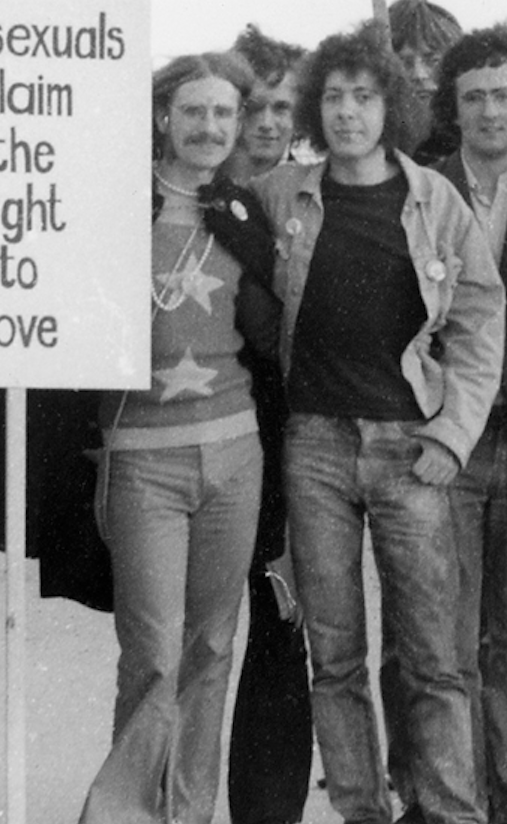

Alastair (on right) next to Colm Clifford at Lambeth Town Hall during the election count.

From a very early age he felt sexually different from other people and always felt as though he was being 'cheated and stared at' for not being like other boys. He was always interested in creative things including art and reading but was plagued by others making 'sissy' remarks about him. He was jeered at because he wanted to be a dancer rather than taking up the usual pursuits of boys such as football and other sports which he viewed as 'a futile waste of time.' He never got his dancing lessons but he was unsure if his parents didn't want that or they could not afford them. He was sent off to piano classes instead which he reluctantly took up.

His earliest sexual awakening happened at school when he was about ten years old having mutual masturbation sessions with other boys. His anxiety around this arose much later when he was in the sixth form. He was 'chased after' by another boy who shunned any attempt at further intimacy. His need for affection was not met. The encounter was 'brusque' and unsatisfying and laced with fears of being discovered that would only add to being castigated for his 'sissiness'.

At the age of about thirteen or fourteen during a school line up in the playground he clearly remembered his first dawning awareness of being gay by just saying to himself "You're homosexual." The word queer or gay never meant anything to him at the time and surprisingly he seemed to accept calmly the fact that he was different. It was only later he began to feel anxieties about being gay with increasingly jeering reactions from 'yobbo type boys' especially sixteen to eighteen year olds in the sixth form because he was seen as such a sissy.

Alastair was a 'fish out of water' because he wanted to dress in 'fashionable styles' which went against the grain of what was permissible in the 'dour' north east of England which he viewed as a "dump" compared to the mellow Lytham St. Annes. He felt that his chances of a more bearable situation would have been made possible in the more liberal atmosphere of London where he could live among a "fashionable clique of kids." His parents continuing lack of engagement with the kind of things he was interested in happened at a time in his life when he needed that extra 'push' from them to discover and become involved in theatre and music events scarce though they were.

In his efforts to find out more information about being gay, Alastair scoured the bookshops for clues. He came across James Baldwin's 'Giovanni's Room' which he stole from a 'store for sexual perversion' because he was too frightened to be seen buying it. In retrospect he felt the book was so negative that it kept him in the closet for years. The message he took from the book was "avoid homosexual life like the plague and at least you might be alright. You might have the title of the disease but you will be alright so long as you keep away from those sort of people."

Despite having gone through primary and secondary school where he was bullied by 'aggressive louts' he had high hopes that university life would be free from 'oppressive male chauvinist sexist attitudes'. He imagined that the higher up the academic tree he went the more "cultured, nice and civilised" people would be. His experience of drunken yobs in the men's union bar disabused him of those hopes. The jeering and mockery continued because of his flamboyant behaviour and outrageously camp dress sense. He dealt with the whistling, yelling, snickers and sneers in Quentin Crisp style by walking straight through people and looking straight ahead without flinching. His whole university life in terms of study and socialising were completely marred by having to deal with this anti-gay prejudice and posturing.

With very few friends and little social life his university days were spent 'sexually' in the closet. He was always camp and outrageously dressed in fashionable and fancy clothes as his main outlet and pleasure. He was never conscious of meeting anyone who was gay and whenever anyone 'gave him the eye' he thought they were being hostile. As a student he went to Grimsby in 1968/69 for two summer seasons to help with harvesting crops at a nearby farm. It was here that he had his first significant sexual encounter as an adult. He was sexually fired up after five or six weeks hard work and, on wandering into a cottage in a local park, he noticed gay graffiti on the walls. He returned a few times to read it all again and decided to try his luck in meeting someone there. The encounter was 'sleazy' with little interest from the man he met but he felt that he 'just wanted the experience.' It was only later, in retrospect, that he realised that a man had actually cruised him in the university cottage.

Alastair inside the Gay Centre

Feeling low in spirit he decided to visit a psychiatrist in 1967 having heard by chance that someone who had a breakdown had found that experience helpful. He wanted to stop being gay and was referred to the University Medical Centre. The Indian doctor he visited said that it could be done. Alastair saw the advantage of talking to someone about 'it' but in the end the advice he received was entirely useless. He kept seeing the psychiatrist who identified Alastair's problem as largely being social in origin and one of social inhibition. Going to parties and dancing with girls was prescribed and 'you can get out of it' type of games were played out. At the end of the sessions an encouraging handshake for his bright future as a heterosexual were not reassuring. The shyness and inhibition when meeting people were still there because of his past experiences of being rejected and ridiculed from early life onwards. He never followed up, as a possible source of help, the rumour that the Roman Catholic chaplain was gay and sympathetic. Nor did he feel able to be involved in cruising around the university library. He continued to feel guilty about being "an absolute Lulu queen."

The only informative chat about being gay and a slight thawing of negative feelings came in his last year at university through conversations with a man he shared lodgings with in a straight household. He talked a lot about sex and intimated that both he and Alastair might be bisexual. He he talked about the pretty boys he had sex with at school. Later Alastair met him again at the Design History Group that he was teaching and it transpired that he was married with children. Alastair met one woman student who was sympathetic because she had a friend who was homosexual. Later through his work with Icebreakers, a radical gay counselling group, he became aware of how many students made contact just before leaving university with anxieties about their gayness, how to deal with it and who to contact.

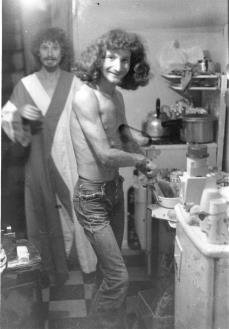

Alastair (on left) with Tony Smith in the shared basement kitchen

In the late 1960s he was aware of underground, counter culture magazines that carried gay contact ads and his indulgence in porn consisted of secretly reading and concealing from view 'health and strength, muscle building' magazines. As an 'outsider' he even rejected the hippie movement that came into existence from the mid sixties onwards. He felt the 'hippie mentality' was 'complacent' and no different from straight society. He rejected the drug culture because he felt weak and vulnerable already and did not want to make his life even more 'befuddled' or bewildered.

He was vaguely aware of the 1967 Act which partially decriminalised homosexuality. It came to his notice in 1967 when driving through England on his way to a holiday in Spain. He saw a notice written up somewhere in huge letters 'Stop the Queer Bill' but was unclear whether it referred to him or not. Later he observed that the passing of the bill clearly made no difference at all to the way he or anyone else was treated.

By 1971 he had moved to Brighton to take up a teacher training course and grown in confidence. He discovered a cruising ground and after one or two weeks he met and slept with a 'strong' man he had fallen in love with though the relationship never lasted. He started cruising much more instead of wandering aimlessly around town 'looking at antique shops.' though he felt his academic and cultural life suffered as a result of cruising. Despite this he started to go to gay bars more. He had heard about them from friends in Edinburgh but found the people there inhospitable and was put off by their 'game playing'.

Alastair (on the left) on his first protest for LGBT+ rights with Sussex GLF in Brighton (1972)

In the same year he had moved down to Brighton he met 'a black man' in a gay bar who told him about the local GLF group. Though it was small he found the group full of 'intelligent thinking people who wanted to do something about homosexuality for themselves and other gay people.' He read about people involved in GLF London and when they were invited to Brighton their political analysis and radical ideas opened up Alastair's awareness of why he was being oppressed. With talk of sexism, feminism and challenges to Patriarchy he placed his own experience of being attacked for being a sissy in the wider context of women's oppression and male chauvinism. Hence by the end of his teacher training course in 1972 he had completely come out as gay. From then on in the age of David Bowie and wearing his own glittering apparel, make up and nail polish he felt empowered and strong enough to go on the offensive around Brighton with others to 'freak people out' and demand gay rights.

By the time he arrived in London he was determined to be out as gay right from the start especially at the college where he would be teaching. He hitch hiked there with no solid thoughts on where to live. It was only by a sheer fluke that he got a place on Brixton Hill via a contact at 'Time Out' magazine. The flat was near Brixton Water Lane which was a notorious cruising ground for sex workers. He shared the flat with straights but didn't get on with them.

Alastair's own words on coming out:

"Well, there I was at the London College of Printing being an outrageous queen wearing badges and jewellery and glitter and all the rest of it......people just stared and gawped and sniggered and yelled and so on but at the same time I was left alone and completely ignored. Very lonely.....a typical straight reaction to gays. They both freak out and at the same time succeed in totally ignoring you."

He was determined to pre-empt all the usual insults he received by throwing it back in people's faces and making it their problem not his. By wearing eye makeup, multi-coloured nails with jewellery while sporting hennaed hair and moustache he deliberately challenged gender and sex role stereotypes. He continued this for three solid year from 1973 to 1976 and took some comfort and fun in the bewildered reaction of students and staff. The bitterness was dissolving.

Alastair had many narrow escapes from being beaten up but this occurred only once at college. Even so it left him with the feeling that he was not safe anywhere and he nearly broke down:

"That was when someone followed me down a corridor and I finally managed to rush downstairs and drop into my room before they knew where I had gone. I locked the door."

Alastair (on right) playing Boy in Out of It, next to Stephen Gee as Straight Brother

He set up the GaySoc and a disco in 1973 but the meetings were poorly attended, "a complete flop" and the discos could not compete with the growing number of gay pubs and clubs opening up. He was disappointed that during his three years as a teacher he had scant success in bringing any students or staff members out as gay. After he had left the college he met a student who came out and experienced the same difficulties in organising the GaySoc and disco. Alastair attributed this failure partly to the fact that "there was no space within my curriculum to talk about gay identity and sexuality." Also he judged the graphic design students, who were predominantly straight, as being "amoral and asocial. Living by example as being someone who is out as gay...doesn't seem to cut any ice with them because they never think philosophically. They never think about these issues...a tiny minority maybe...almost always women."

What Alastair pointed to was a lack of any rigorous academic culture and questioning of the the world and its ways that were to be found in other higher education institutions such as universities. His cynical views about students were driven by the belief that the narrow focus on technical training as graphic designers geared towards the commercial world they would be working in stripped them of any awareness or interest in human affairs beyond their career expectations.