Julian Hows

Interviewed by Bill Thornycroft in 1984 and Ian Townson on 2nd July 1995

You can read more of Julian’s memories of the Gay Centre here

Julian Hows on his last day at work as a guard on London Underground

photo credit: Robert Workman archive, Bishopsgate Institute

Julian How’s early experience of gay politics has already been remarked upon in the account of his exploits as a 15 year old pupil at Tulse Hill Comprehensive Boys' School. After the establishment of a commune of radical queens at 9 Athlone Road, near to the school, bewildered and outraged local school kids, parents and teachers vented their disapproval. Despite the best efforts of the communards to offer dialogue and an explanation of who they were violent attacks on individuals and the gay household continued and meant, despite reinforcements from other West London queens, the reluctant but inevitable retreat from hostile forces to a relative safer haven of the Colville Terrace gay squats in Notting Hill Gate.

-

Julian left home at the age of 14. He was 'shunted out' of the parental home to live with a neighbouring 'very good' friend of his mother:

"She sort of offered me a room in her house. She said come across and live with us while you are taking your '0' levels for a year or so. Then we'll decide what happens. I just couldn't live at home. It was too pressured. We were in a very, very cramped flat and I did not get on with my father at all. I threatened to kill him several times and he threatened to kill me and it had already been discovered that I was passing through a ‘phase’ (laughter)."

He shared a room for about 6 months with her son who was several years older than him and, as onetime England schoolboy sabre champion, had been tipped as a possible member of the Olympic team. Julian recalls:

"He could have represented one of the West Indian islands....because he was a dual national....his father was from Barbados. He had a big chip on his shoulders about being black and said he wanted to represent England."

Julian thought the young man he lived with was 'sweet and nice' though at times somewhat 'supercilious' but had no 'inkling' that he was gay. His relationship with the woman and her son soured when Julian was accused of 'corrupting' the son who was 4 or 5 years his senior.

"I was accused of everything under the sun and told to get out and never darken their doorstep again. That was when I went to live with my grandma."

Julian has very fond memories of the time he lived with his grandmother:

"......she was very sympathetic towards gay people. In the best sense of the word. Sympathetic in the sense that very old people are sympathetic towards younger people. Especially in the way that grandparents are sympathetic towards their grandchildren. So that was very nice. My being gay was very much merely another part of her sympathy. There was nothing special, there was nothing condescending or patronising. So that was fine, fabulous, wonderful. You know, she didn't want me out on the streets frightening the horses but we had, sort of, some unsaid understanding. She thought I ought to take the little boy next door, who was four years younger than me, to the ballet and things like that."

Julian returned to his parental home for about 6 months but tensions arose once again, some of which related to his expulsion from school for his gay political activities. So he packed his bags and went to live in a squat in West London:

"I lived in a squat in Notting Hill Gate with about eleven other gay men In Colville Terrace and from Colville Terrace I moved to Colville Houses into a commune where I learned the basic skills of how to cook, how to relate to people, you know, what honesty is all about, what awareness is and I listened to an awful lot of Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. I wore an awful lot of drag and existed on social security and supplementary benefit for a very long time. I didn't go out on the gay scene at all except the 'alternative' which at that time was just about beginning to get itself together. I was really living on another planet to all intents and purposes because when I met other gay people, even those who were connected with Gay Liberation, they were either all academics of one sort or another, who had a comfortable lifestyle and were merely dropping out and hadn't quite decided how far dropping out was or what it meant so they used to come round and regard us as a curiosity."

"On the other hand there was the gay commercial scene the high point of which was at that time the upstairs room at the Boltons on Sunday lunch times with, sort of, mad Spanish queens wandering around with fans. Acid, dope and whatever were being sold all over the place. As far as I was concerned, on the rare occasions that we visited it, I could see then it was just one stage on from cottaging in Brixton cottage. All the same sort of predatory games were being played and I thought to myself, well, I don't want to know. So what used to happen is I used to fall romantically in and out of love with the people I used to live with at the time or with people who came round to see us because we had very much an open house policy. The rest of the time I was virtually celibate. In fact I was celibate for an awful lot of that time. That‘s a lesson to be learned. You know, Gay Liberation and living in communes does not necessarily mean free or group sex. I tried it once or twice and I can tell you all about it if you really want to know. So that was where I lived."

"After that and out of that I started to think is this all there is to being gay? I actually started to live in a flat with a woman and I lived there for about a year in a monogamous relationship. That was my first truly monogamous relationship. This was after Colville Houses and then after that I moved into another one in Latimer Road with Richard Chapple.

In contrast to the hostile environment of Athlone Road in Brixton Julian clearly stated that living in the Colville Houses and Bethnal Rouge communes together with his two 'monogamous' relationships felt like being part of a gay 'clique' in a protected environment though with the positive effect of "a lot of other gay people to help me get myself together".

Julian moved back to his parents house and for once had a separate space to live in. It was a tiny 'broom cupboard' that had been a scullery. Now that he no longer had to share a room with his brothers, for the first time ever, he was able to take someone home:

"For the first time I had actually met someone from the same kind of class upbringing as me. You know, both sort of sons of once removed Irish navvies. So he wouldn't be upset by what l am bringing him back to. So I brought him back and to John Lloyd's credit, who I intended to live with, he didn't sort of show any noticeable signs of stress that I had asked him to sleep in a broom cupboard with me (laughter)."

Things didn't run smoothly for this first homely sexual encounter. Julian's job as a a guard on London underground meant an early rise. Arriving back home after his shift as a London Underground guard he was surprised to discover the young man he had met and enjoyed the pleasures with during the night had not departed.

"He got ill over night (laughter). Suddenly, I arrived back 8 hours later thinking... I'll phone John up after I get home. He was still there. My mother was wandering around saying quietly "He's still there. I brought him in two cups of tea. I offered him breakfast. I walked in and he was iIl."

"I had to get a car to the house, carry him down the stairs wrapped in a blanket, you know, he was only just about dressed, put him in this car and took him all the way home to Vauxhall. I wrapped him up in bed and went out to buy a half bottle of brandy and an Indian take away to sort of feed him and cosset him. After that, I thought, if this is what you get when, for the first time ever, you take someone back to the parental home....if this is the effect it has upon people well, you know....l was quite annoyed that he had allowed himself to become ill in those sort of circumstances. It wasn't a very good show, you know. My mother wandering around thinking every time homosexuals did it this sort of thing this happens (laughter). You know, on an academic level I had fought most of the battles with her but the proof of the pudding is in the eating and there she was experiencing a homosexual relationship ten feet away from her and this sort of thing happens."

Impressions of the South London Gay Liberation Front and Journey to the Gay Centre

Julian's route to the South London Gay Community Centre went via the SLGLF meetings at the Minet Public Library where he received an ambivalent reception from those who were wary of the dangers of having a teenager at the collective meetings. The pushy charms of an 'underage' but actively ‘on the make’ gay youth had to be treated with caution as he was considered to be jail bait. This experience soured Julian’s attitude to the so-called radical gay people at the SLGLF meetings and almost put him off attending further functions. It was important for him to be able to go to the meetings and discos because he was reluctant to socialise on what he had already experienced as an inhospitable 'straight' gay scene. Despite the caution exercised by those at the SLGLF meeting Julian still picked people up and he felt that they "....were , sort of, chicken hawks who...under the guise of going to Gay Liberation meetings were playing out exactly the same kind of relationships they would play out in Brixton cottage or picking kids up at swimming baths....it was with a slight sense of foreboding that I actually went to the Gay Centre. I was agreeably surprised that it was nicer than I thought it would be."

His Notting Hill period had been lived among a relatively self-enclosed, self-referencing group of radical queens who made little contact with others outside that milieu especially not the ‘straight’ gay scene. On one or two occasions when Julian had visited the gay scene, as mentioned earlier, he was disappointed with Sunday lunch times in the upstairs room at the Bolton’s in Earls’ Court. At least the commune in Notting Hill had provided a space in which to learn the basics of "how to cook, wear an awful lot of drag, talk frankly to other gay people and to exist on social security and supplementary benefit for a very long time." In other words a creative space to explore and find one’s interests and direction in life away from the ruthless, competitive distractions of the ‘straight’ world. But Julian was equally critical of other GLF people. Academics who were gay and from a relatively ‘comfortable’ background would drop in to the commune to share an experience with radical drag queens but soon departed unsure of just how far they wished to ‘drop out’ with their new-found curiosities.

After having lived in a "chic radical collective or two" and his experiences at the SLGLF meetings it was with foreboding that Julian went to the Gay Centre but things turned out to be better than he had expected. The tawdriness of the physical surroundings, described by a Times journalist as "a shabby set of rooms in Brixton's black area" was more than matched by the friendliness of the atmosphere. His notion of the ‘lowest common denominator’ denoted the unstructured nature of the set up at the gay centre. By that he meant the centre was an easy going drop-in place with open access and no-one was likely to freeze you out if you did not have the correct credentials of respectability. No social graces were needed that would be de rigour to fit in to other tightly-knit groups of people already in possession of a ‘cliquey’ and excluding set of rules and regulations. There were no rules to play by other than that you were gay and willing to negotiate the process of ‘coming out’ with no strict prescriptive rules on how to achieve this:

"The mere fact that you are in a social setting, you are gay and they are gay, is actually going to open up a lot of doors towards you having an unstructured type of relationship or interchange. You very quickly find out that all the old divisions like class, whether one is living out that class situation or not, or whether it is just in terms of the social graces or whether it is in terms of....am I going to allow this person to relate to me because they are unemployed and have got no money and I am holding down a nice, comfortable job and I've got a nice, comfortable flat....those things didn't seem to be as important. So consequently it was just working on a lowest common denominator factor that you were gay. There was far more possibility for growth of relationships of a social nature. Far more give and take. That's what I mean by friendly. When I first walked in there, far less cliquey, you know, than most other groups where you have to play by the rules of that particular group or you're not wanted. Friendly in that sense. At the same time the actual physical surroundings were, I mean to say the least, were like bomb culture. It wasn't very comfortable but at the same time it was very friendly. It was a pity that the two went hand in hand (squalor and friendliness). But they do that in all sort of, all open networks like that."

Julian's chief recollections of memorable occasions at the Gay Centre, apart from getting drunk on scrumpy cider out of chipped mugs and talking to 'dossers' who wandered into the place, is the four hours spent in Brixton Police station after a mad axe man had got into the centre and wreaked havoc. Also after the centre had been evicted he recollected moving back in:

"I can remember wriggling through a second storey upstairs window head first and ending up in the loo pan (laughter). Going downstairs and jemmying off (opening) doors and such like to get back in. I can remember rebuilding the place."

Julian expressed clear opinions about the fate of the Gay Centre and the direction it would eventually have gone in had it remained open. He also raised the question of why it failed:

"....It would be a community centre in exactly the same way as any neighbourhood community in any Inner London Borough has got a community centre. That might only be used for tenants’ meetings, for a whole range of meetings and it might not actually be very well used. It might have an opening evening and it might be used by a local MP for their surgery or a local councillor for theirs. It might also be used...for an under 5s club during the day or as a drop-in point for pensioners in the area."

"If there was a gay centre there today, it would be, as far as I am concerned, a community centre that would be very well used, very well utilised and together. Very nice. It begs the question why wasn't it. The reason I believe it isn't there now...is that people weren't actually able or skilled enough to maintain the survival of that space. What's more that space provided a focal point, an energy, where people used that to get into other things. It was very important as a melting pot. It was very important as a place where the batteries were created that started a lot of people off on a lot of other things. l don't think the internal wranglings that went on in 75/76 have in any real sense much to do with why the gay centre exists or doesn't exist now. I don't think that is a real issue."

"I agree with what you said about perhaps the people who were holding it together in whatever way found a gay community centre around the houses that they were now living in....consequently what happened was that the untogether people took control of the centre most of the time and that's the reason why it collapsed. I don't think that actually even the people who had moved into these houses in Railton Road and formed the basis of the gay community as we know it....in any real sense had the expertise to maintain the gay centre anyway. I know that I saw the gay centre as being a means to an end rather than an end in itself. I think, honestly, that is what most people saw it as. Even people like yourself Bill (Bill Thornycroft, the interviewer) who used the gay centre to a certain extent to build up a new kind of social network, right."

-

Julian felt that the short-term, 'means to an end' approach of Gay Centre users led to a lack of investment in and commitment to its continuation into the future as a social and political institution.

"The gay centre existed as a means to an end and that is basically the way community centres exist... If for example people had been that interested in maintaining the gay centre as an end for other people after they had moved on from it, then it would have been a relatively easy thing to do, for example, to create the finance. To move that to someone else. But if you think about the commercial properties in the area at that time we could have done it. I think it's a bit of a cheek to say that because of the political climate at the time we were actually not prepared to put our own money into it. To give ourselves nil rating or a peppercorn rent that's what we were asking for in 1973 (1975). It's happening with the London Lesbian and Gay Centre in 1983 (1984). l think that's one side of the story, yes it would have been wonderful if we could have got that together in 1974/5 but....the thing is everybody walked in there as a means to an end. You know, in the short term, opportunistic sense. That's why it is no longer still there or something like It isn't still in the area."

Even though he felt that people used the centre as a means to an end it also had positive value:

"...to find a circle or a set or a peer group to which they felt they could belong. I think it provided that for an incredible number of people. It provided that for me definitely."

His reasons for the gay centres demise:

"I am not decrying the community in.....relation to the gay centre (the Railton/Mayall Road gay squats). People got themselves together and the gay centre was no longer relevant. But because the gay community centre was no longer relevant the community gradually dissolved and fragmented. As far as I am concerned the gay community in Brixton is at the moment (1984) comparable to the gay community in North Kensington. It may or may not produce something. It may be just a community without a focus, you know, in the same way that an awful lot of Jewish people live in Golders Green."

-

"I actually thought that that was one of the facets of being an open access facility and to a certain extent I regard it as a pity that we didn‘t actually move on from that....that we didn't turn into a South London version of London Friend (hence more secure). I regard that as unfortunate....As to being frightened by violence, yes of course one is frightened by a violent situation but at the same time what it actually means is, one is living through violent times and either you exist within them and try and make your peace with them or you get out. I am one of the people who stayed. Violence? I mean to say, why live in Brixton, you know. If you don't see violence as being the end result perhaps of allowing a certain amount of chaos, you know, If you allow a completely unstructured situation then unfortunately I do think you are going to get the possibility of violence. I think the possibility of violence is more frightening than the violence Itself. But seeing that the gay centre had that open access policy then it is something which to a certain extent we all ended up living with or living under the threat of."

-

It became the rule of the day that the Gay Centre should be clearly identified as a social space for gay men and lesbians. Trans people were scarcely considered at the time and bisexuals were approved of provided they identified politically as gay and against the oppression of homosexuals and lesbians. Bisexuals, who could easily pass for 'straight', were also warned not to display 'heterosexual' relationships at the centre that would put gay people off from attending. Julian has very clear views on these issues beginning with Malcolm Greatbanks our South London Gay Liberation Front Candidate in the 1974 General Election:

"I actually thought to myself, yes, that is very bad, very bad, tactically. It was very bad that Malcolm Greatbanks was seen on the campaign trail advertising in the arms of a woman (Sue Wakeling the election agent) rather than the arms of a man. Election agents were supposed to stay in the background whatever the eventualities anyway. But then again at the same time would they ever have allowed a picture of Malcolm Greatbanks (kissing another man?) or a group of men (Kissing?)."

Julian added to the controversies the question of a class divide between the 'nerds' and those running the gay centre.

"If it comes down to a question of whether bisexuals ought to use the gay centre, whether heterosexual relationships between avowed bisexuals ought to be allowed to exist on the premises and things like that, then I think it is more a question of class....the middle classes use duplicity and the working classes are confused by duplicity. l think it could be looked at as a class argument that....that the nerds in the centre who were in the main talking about bisexuality being the answer rather than homosexuality or heterosexuality could all be regarded as working class and the people who had been running the centre and who had moved into the echelons of 157/159 Raliton Road and the bits of Mayall Road could be regarded either as downwardly mobile middle or upwardly mobile working class. Maybe that's the thing of those people not being able to, the working class people not being able to contain that duplicity in areas of sexual politics...."

"It's very interesting that the unwritten rules that we were making for the gay centre were very much that anybody who walked through the door should be able to see a homosexual relationship blossoming before their eyes. Perhaps.....that they were seeing the undercurrents all the time of heterosexual relationships from people who were describing themselves as bisexual and that in itself might have been a good thing that people were describing themselves as bisexual but they couldn't get it together politically to describe themselves as gay. (politically?). As far as I am concerned when you're talking about what the struggle for sexual politics is all about....people's sex lives are actually private. What they do in bed should only be the concern of them. When it's consensual, that should be the only a priori for sexual relations but when you are talking about how to present oneself on a political front then it goes back to the old adage of gay liberation is personal liberation and someone who can't describe themselves as, especially more so in 1973/74/75/76, as being prepared to stand up and be counted (as gay), then they were actually copping out. It is unfortunate, as far as I am concerned, that it was a farce situation that those people could not see the validity of what that was all about. They used their lack of knowledge and understanding to talk about cliques and hierarchies and actually take a very sound anarchist position. In fact on a political level they were taking a very sound anarchist position. That's why as far as I was concerned I wanted to stand above all that. As far as l saw it the gay centre had merely been a means to an end. Honestly, I think that's the way that most people saw it."

-

By the time Julian left home several houses had already been squatted on Railton and Mayall Roads by gay men. Initially there were no hard and fast rules about who lived where and often, if you were known to the occupants, acceptance was given 'on the nod'. Later some households adopted more formal 'interviews'.

"....the house next door to 159 Railton Road (157) had been opened up by Henry (Pim) and Andreas (Demetriou) who lived there for three weeks before they fled back to the Victorian comforts of Villa Road. The house was empty and Peter Petal (Peter Cross) and his flame of the moment Robbie (Roberto Campagna), Robbie the Italian robot, had moved into the house and Petal was concerned, I think, that he was living with a lover who didn't speak any English. He was....southern Italian with all that implies and was very much using Peter....as not only his lover but his translator, mother, brother, sister, friend etcetera, etcetera, etcetera. I think I was sitting there saying...I can't go on living where I am at the moment. I've been rushing around looking for flats. Everything seems to be falling through. Petal said “Oh, do you want to live in 157 Railton Road" so I said "Oh, yes". We walked upstairs and he showed me a room and said "When do you want to move in". This was a Wednesday or Thursday and I said "Saturday please". He said "Yeah, sure. Fine." So he gave me a key that day."

"He said to me next day "Oh that's fine. I've asked Robbie and it's alright. It would be a good idea to have a third person living in the house." So there I was the next day collecting all my stuff from my own house and arranging to pick up all the stuff from Latimer Road (Notting Hill) and what was wonderful was that I was given a key and told I could move into this room or that room and I said I would be moving at about 12 o'clock on Saturday when I had got a day off work. They said fine and when I actually arrived there was a little note saying "we've gone out. Go in and put yours stuff where you like and we'll see you when we get back". Actually, I've decided it's the perfect way to move in anywhere. With the people you're moving in with being out, when you are carrying in the furniture and everything, you don't have to explain where you got it from (laughter). It's not from Heals or it is from Heals or, you know, sort of how that leg came off. You're allowed just to sort yourself out and that's what I did. So I moved into 157 Railton Road."

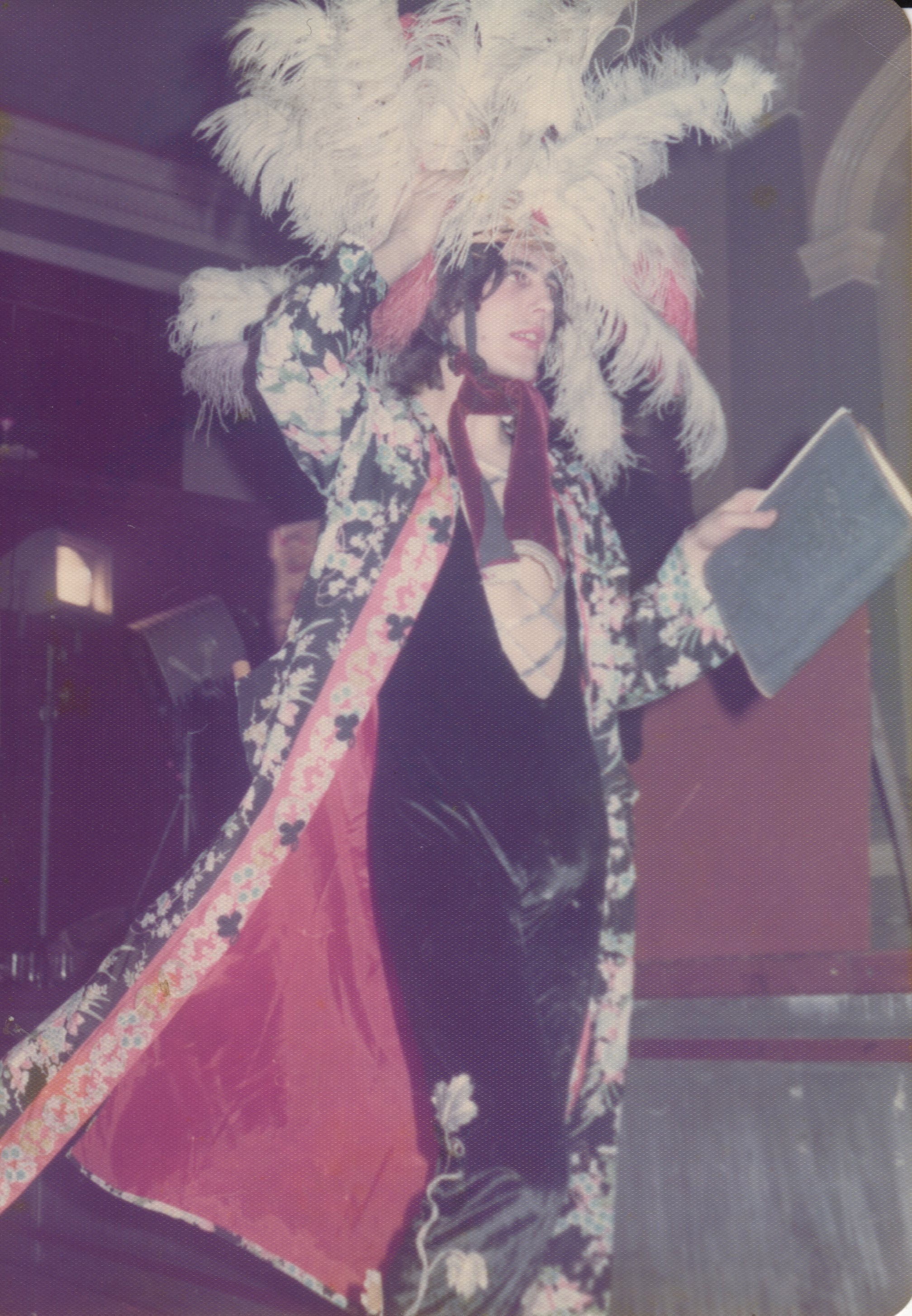

Julian Hows in a performance by Brixton Faeries theatre group at Fulham Town Hall

Julian in his spinning hat creation

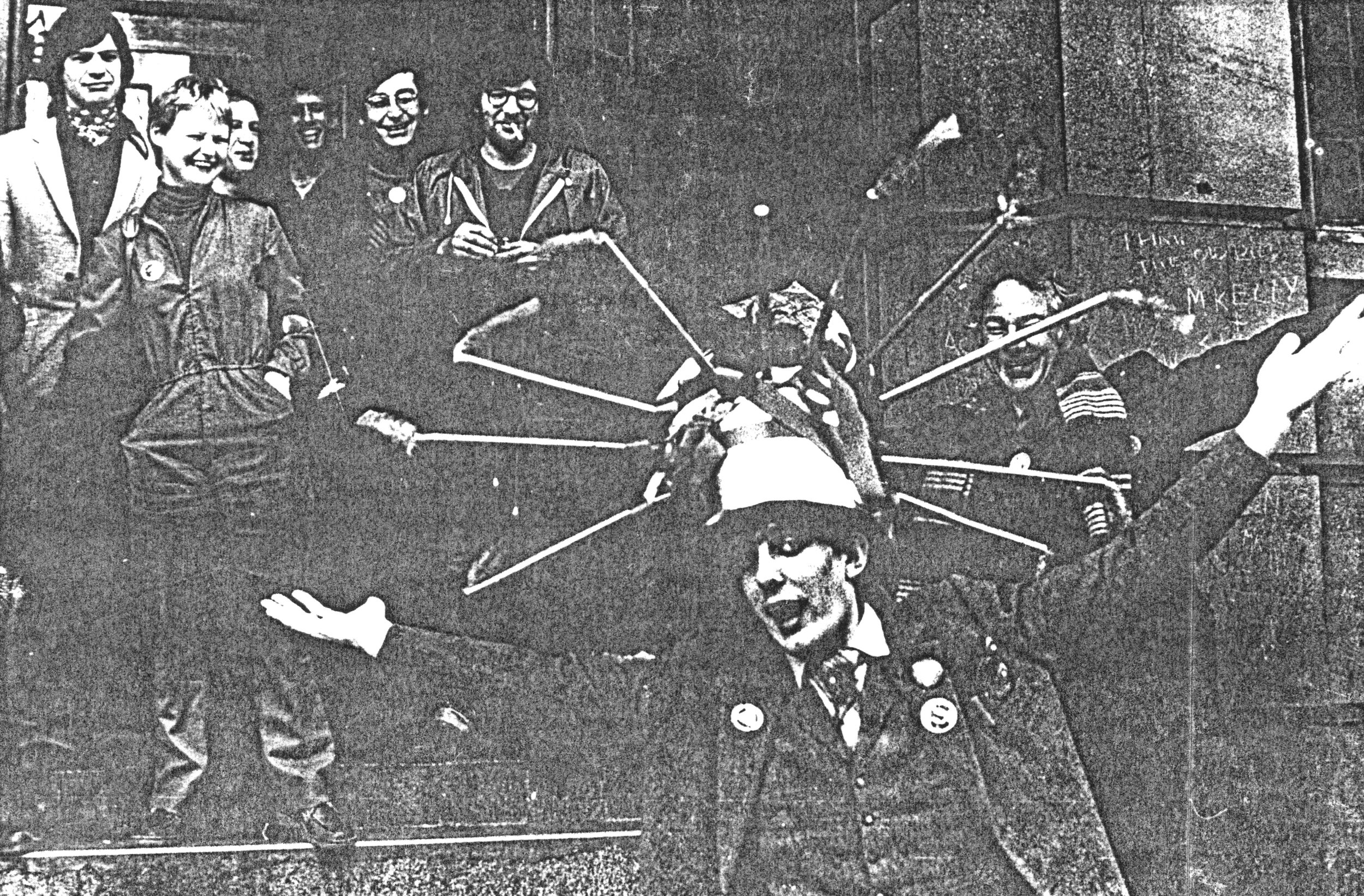

Background L-R: Peter Cross, Julian Hows, Foreground L-R: Peter Vetter, Ian Townson

-

The radical queens in the communes at Bethnal Rouge and the Colville Houses saw themselves as ultimate revolutionaries opposed to cooperation with other groups and were seen as 'separatist'.

"As far as Railton Road is concerned the differences between there and Bethnal Rouge and Colville Houses was that there the situation was a communal lifestyle whereas in Railton Road it wasn't a communal lifestyle In that possessions weren‘t shared, money wasn't shared. At the same time monogamous relationships were not expected of one but they were allowed. However you were not allowed to step on somebody's toes just because you were in a pair bonding relationship and power blocks were not allowed to form in 159 and 157."

"In Bethnal Rouge and Colville Houses monogamy was not allowed . Well that is not quite true. It is more that such relationships had to be ‘justified’! We had all signed up to the notion that we were not going to imitate or parody heterosexual norms; pairing off into exclusive, monogamous couples was an example of parodying the heterosexual (and Judaeo Christian and Capitalist!) ideology which was putting down gay people . The sense of what a ‘commune’ should be was also slightly different in Bethnal Green and Notting Hill - personal growth and consciousness raising came first and foremost. There was the view for example that "Oh my god were not going to get involved in the squatters’ movement until the squatters‘ movement takes cognisance of the fact that we are gay etc." So other groups and alliances with them often went through a ‘vetting’ process – were they radical enough to be aligned with! This was quite different in Railton Road at 157 and 159 and the house at 146 over the road (Mayall Road) and other gay people who lived around, all in separate units, might have seen a Gay Centre as the focus of their struggle or a Gay Centre as the focus of the gay community which was springing up around there which in tum had relationships with other communities, other patchwork minorities which were in the area."

Maybe these differences could be be explained by the timeline. The Notting Hill and Bethnel Green communes took place in the the ‘furnance’ of GLF exploding on the scene in 1970-73 and arose from and were created by people heavily involved in that tradition. Whereas the Brixton squats happened slightly later and in part arose from the SLGLF meeting – a lot more sedate and less confrontational than the very early GLF meetings. So maybe just a sign of the natural progression from the very necessary questioning everything – and most definitely each other (are you really liberating yourself and challenging all those heterosexist assumptions) into something more pragmatic and self-assured , if no less radical!

"In Bethnal Rouge and Notting Hill Gate it was a question of - they were the whole thing. So it was much more difficult to establish liaisons with other things because we were already very much seen as a symbol of something but not related to in any real sense. Yes, I had read all the tracts from the womens movement , from the (few at the time) radical and revolutionary thinkers in the gay and black movements, as well as a smattering of Marxist-Leninist gay thinking which the radical queens rejected! However putting those theories into practice in a deeper way and building up a political sense of what it was to be gay in the ‘real’ world as opposed to the ‘bubble’ of the early communes started to happen through living with people in Railton Road. Whereas what had happened before, it was a strange thing, we had been putting the practice before the theory. The practice was all there. We could zap anything and anywhere, you know. My practice was altered very much by the process of, the formulation of principles that I had to reason and argue out. You know, to support the practice I had been Into and continued to be into. An extension in that I started to think about other things, about other ways of looking at things. My view of life changed from the input I was getting from the other people I was living with, but I wasn't actually changing to the extent that l would sit back and think "My god l shouldn‘t have behaved in this way if I now believe this." It fitted in quite nicely." Part of growing up once again …

-

"Okay, so I moved in with Petal and Robbie. Then after that for some strange reason which escapes me, which probably means I don't want to remember it, we decided to knock a hole between the two houses, between 157 and 159 Railton and become one big happy household. I can't remember why we did that."

"Peter Vetter became a permanent fixture in those two houses. So we decided to move into a semi-communal situation. I pressurised it, I think, because we had a very small kitchen which was silly really. At the time we were suffering under the illusion that you couldn't move gas pipes and things and plumbing."

"We had a bathroom and they had a decent kitchen. That in itself was an example of our own short sightedness in that we let the physical environment of where we were living dictate how we lived rather than the other way round. It would have been just as easy in fact to bang an ascot heater in 159 and move our kitchen. Looking at it, it would have cost a hundred quid altogether. In effect it would have been the easiest thing in the world to have done that. I don't think it was any hight fault in sense of us all wanting to live together. It might have been a question of thinking seven people might actually create more energy and out goingness than two groups of three and four."

"Despite the fact that we were living a communal life we all split into factions. Very quickly. We split into a me and Colm (Clifford) faction and a Jamie (Hall)/Petal(Peter Cross) faction. Later there was a Jamie/Petal/Peter faction and a David Callow faction and a Robbie Campagna faction. Then after that we had a David Simpson/Peter Vetter/Robbie/Petal faction."

The divisions between those who were into 'personal growth' and those who had other priorities such as work and defending ethnic identity. How those engaged in 'personal growth' adopted 'exclusivity' in their choice of sexual partners.

"Basically Colm (Clifford) and I ended up being outnumbered. We felt outnumbered because, to a greater or lesser extent, I was trying to trade off the amount of money that I was bringing into the house against any sense of personal growth and Development. Colm was in fact playing off his individuality....the fact of him being an ethnic minority (Irish) in the house against any personal sense of growth and awareness. We were in fact cutting out an awful lot of what was going on because I don't think what Petal and Jamie and David and Robbie realised is that it wasn't so much the personal growth that we were afraid of it was more a question of how their personal growth had built up between the three people involved, four people when Peter moved in. They were all madly sleeping with each other...."

"I actually think (personal growth) was based on the fact that if those two people had met on the gay scene they would have hit it off anyway to a certain extent. Quite frankly I'd been through all that. (They) repeated the same mistakes, as far as l was concerned, as the gay scene in that you go to bed with somebody or you have sex with somebody or you get involved with somebody because of the external pressures that you find which happen whether you fancy them or not. That is the thing that drags you together. I'd been through all that and to me saying "You're gay and I'm gay. We ought to explore each other and that exploration should not end at the bedroom door", as far as I was concerned I'd been through all that and I didn't want to recreate it at the time. For me it was something that I dragged back from."

Julian was asked if the factions broke things up leading to him moving out.

"What a happened was Colm moved out. Colm did a dirty on me. My best friend did a dirty on me. he decided to live with another Irish expatriate. Closer to being Irish than I was. Also he knew a little bit of Gaelic. He was first generation immigrant rather than second generation immigrant like I was. So he moved into a house with them after we had spent months saying to each other we've got to find somewhere to live, the two of us. This first generation Irish person had an Australian lover called Jeff. So that was Terry (Stewart) and Jeff (Saynor). Colm moved out and I moved into his room which happened to be the last room there apart from Robbie's which I couldn't move into. I became basically very alienated from the other people that lived in the house. Mainly because, for most of that period, I was the only person working in that houses and things like that. I had another way of realising what I was doing."

"It ended up with me having all the trappings and the suits, me being the only person working in the house. Being able to get out of a lot of things. Basically I was being very opportunistic. But at the same time I thought that all the major things that were being done to the house over that period l actually helped with. All the minor day to day things I couldn't be bothered with. That created a great deal of antagonism. I can remember Petal (Peter Cross) for example, in a thirties house coat, it was wonderful, like one of those thirties aprons which was like a dress in everything but sleeves with a little tie at the side. He said to me: (in high-pitched, annoyed tones) "l'm pissed off with you not doing any house work. I got up. You had a dinner party last night. You cooked and used every bowl in the fucking house. You did all this and I got up yesterday morning and I didn't do the washing up and you came home at 4 o'clock and then had something to eat and then went up to your room and then went out. Then you came home and got up the next morning and then had a cup of tea and went out to work, came back and you still didn't do the fucking washing up."

"I thought to myself, to a greater or lesser extent that was very valid and very true, you know. But at that time I was working and would rather have turned round and paid someone a tenner to come in and do all the hoovering. Paid someone a tenner for four hours cleaning up and doing all the shelves in the kitchen and the washing up in the sink than actually do it myself. I was working very strange hours (shift work) and a 40 hour week (at least) and wanted to enjoy myself. At the same time when I found myself pissed off because someone hadn't done X, Y or Z, I took it out on persons for reasons that didn't necessarily have anything to do with the amount they were putting into the house or taking out of the house though l didn't realise it at the time."

"You know, like putting washing up in peoples‘ beds. Lifting up bowls and putting them in Robbie's bed which I did on one or two occasions. It would be very interesting to know how people who I lived with in 159 and 157, six years later, what they actually think of me now. Whether they'd be prepared to live with me again. l mean to say, that would be the proof of the pudding as to whether it was a successful inter-relationship of personalities. Because, not necessarily all the time is that kind of conflict non-productive. I'm a great believer in the principle that the....as Tennessee Williams has proved in "Whatever Happened to Virginia Woolf“ and "Long Hot Summer" that sometimes a relationship isn't a relationship, not necessarily a sexual relationship, until the lows of the relationship completely parallel the highs. If you like somebody and show your liking towards somebody you ought to be able to show your hate towards somebody just as much. When they are completely parallel it sends you bouncing off in directions which just maintain energy. Lovey-dovey relationships with people....or relationships where you don't talk about those things with people to me are not relationships anyway. They end up with the type of relationship where you meet someone (whispered) where you don't know what to say to them. We have nothing to say. (Normal voice). That to me is where you stop. With people that you haven't seen for sometime that you might have perhaps lived with, until you actually get on to things that you have a difference about, and not until realising what the polarities are do you actually realise that you are still important to each other. You are still an important focus in that person's life - perhaps."

-

"I've mentioned all the bad things about living in Railton Road. What are the good things, the good moments, occasions. What were the happy times? The nice parts are all those things which are so commonplace. Like the simple thing of feeling a sense of belonging to a group of people...having a family. Being able to come in at whatever time you get in and knowing that somebody will get it together to cook a meal about 6.30 or 7 O'clockish. Occasionally you'll do it. Having a sense of you all sitting around the dinner table, you know, dinner's over and there is someone you are able to rely upon and they can rely upon you even when you say "Right we've finished. Who's doing the washing up tonight then?" Or let's go and do this and let's go and do that and being able to sit

around a table with 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 other people and not feel any pressure or any need to perform. As far as I am concerned, the greater number of people you can actually do that with, then the nicer it is. The better it is. It's very difficult to say what are the good points of living in a group of people."

"....it was very obvious that a group living in what was to become a period of over two or three years, did become a homogenous unit to some extent. You could walk from one house into another and there was always entertainment in that there was always....life without television, which I think is a wonderful thing....leads to an awful lot of drive and energy being created. You know, when you've got seven houses (nine in 2020) which back on to each other, each of which has its focal point, you know the focal point where those people as a unit receive guests as an open space.....whether that be a kitchen as it was in some houses, a living room as it was in others, whether it be somebody's room in that house there was always all that...being able to walk into any of those spaces was better than having a very high quality 24 channel television. It generated ideas and energy and that was the ‘entertainment’ that was going on. At the same time...the homogenous unit that was created never actually realised....a group dynamic. It never had a group dynamic except through Gay Liberation South London, except through the Gay Centre. That was its group dynamic. I don't know why that was."

"It is very unfortunate that it was like that because that means, ten (nine) years on in 1983, that group have got a housing co-op that is intended to split most of that in to 12 one person units. Through the aegis of a housing co-op that doesn't have the word ‘gay’ in the title. It is very interesting that what has been shied back from is that group having a dynamic as a group. To a certain extent, even though there are perhaps what, about sixteen people living in those properties now, there have been something like fifty or sixty people that have gone through those houses in those years. If you work it out over a ten (nine) year period including those who stayed for a few months or even less that's only a change once every two years. You'd actually think that there would be a sense of continuity and a sense of growth of the group as a unit and it hasn't happened. It never happened. That's because the good things that happened to that community have happened by default rather than design. That is unfortunate."

-

"The 1978 'Brixton Gays Welcome Anti-Fascists' banner. Held up with 2 inch thick rope. Made out of pink denim. I got it cheap. It was only 50p a yard. This man in Brixton market, at the bits of cloth shop, had all this pink denim and said "I haven't been able to sell this at all." So, you know, I said, ‘Well, you know darling, it is pink denim." So l said how much do you want for ? yards of it? So (we used) pink denim and it was with blue felt that Petal actually cut out all the letters. One of the nicest things is the fact that we strung it up in the back gardens between 149 (Railton Road) and Henry and Andreas‘ (148 Mayall Road) with this bit of rope. We were working by candle light. It was absolutely impossible to try and get a needle through this denim and through the felt which kept on slipping. This was about 10.30 in the evening. We strung it up and it was so heavy. You just would not believe how heavy it was. We actually had balloons behind it. Balloons and l think we had a dragon head behind it as well. That was quite camp."

"They way it came about at first was nobody would tell me the route of the fucking march. Whether it would come up this road (Railton) or down Dulwich Road to the park (Brockwell). I found out from somebody in the NALGO offices as was then (now UNISON) down in Brixton (Acre Lane). The thing is we had to find out what time the buses, what time they were going, to stop the buses from going up the road. We had this terrible thought about whether we could get it high enough so that the buses wouldn't hit it. We actually ended up putting it up and having to stop a bus. To stop the bus because what we actually did was, across this side (gay squat) it was simple - we just got up on the roof. Across the other side what we actually did was we jammed a broom stick and two towels across the inside of somebody's window frame. We held that there and then passed it (the banner) up from window to window all the way up to get it to the top window of their house on the other side of the road. Of course it broke because of the weight. We had to slacken off the rope here and drop it all the way down. Peter Vetter did one of his butch Australian outback knots and we had to haul it all the way back up again. These poor people across the other side of the road who we had gone over to and essentially said "We want to put a banner up for X, Y, and Z. We were thinking of attaching it to one of the lampposts but we just couldn't get up it. Do you mind if....it won't damage your window frame too much" (laughter). And eventually as it went up they said "WeIl, I suppose so" (bemused tones). You could see their window frame groaning (under the weight). Basically you had 60 feet....round the other end (other side) it was rapped 12 times round the whole of the chimney stack. So it was like Elvira Madigan time."

-

1. Of the twenty or so dances at Lambeth Town Hall organised by the SLGLF he only ever went home with one person: "Be radical and join a monastery."

2. The misunderstanding that his 'self-centredness' was mistaken for narrow egotistical posturing when it was a "focus against which people can get themselves together."

3. Falling off a roof and sustaining serious injuries. Spending many months with a wired up jaw and drinking liquidised food through a straw. With the squats in various states of dilapidation leaking roofs were one of the hazards that needed to be confronted. He climbed on to the roof of 159 Railton Road with rags and aqua seal to plug the gaps. Responding to Bill Thornycroft's question as to why he 'jumped off' the roof:

"I did not jump off the roof, I'll have you know. I didn't. No, that had much more to do with me as a person having a fatalistic....l decided at the age of 9 that I'd die when I was 26. I am 28 now and I'm still here. I reckon I am doing pretty well. I am 2 years above what I should have got. I didn't jump off a roof, no, nonsense. Slipped. Slipped. Did he slip or was he pushed? I was pushed. I was pushed! What was I pushed by? I was pushed by all these leaks In the roof. These terrible leaks in the roof which nobody was doing absolutely anything about. Quite frankly that was my period of greatest alienation from 159 Railton Road and after that (fall from the roof) they had to be nice to me because I was injured."

4. Drug Bust

"The reason they raided us was....l tried to start a window box. Nothing seemed to grow so rather than flowers I went down Brixton market one day and bought these windmills. You know, the little kiddies windmills. I stuck them all over the window box. As l came home from work I noticed that the windmills weren't catching the wind. So I used to tum them so that they could catch the wind. The police thought that this was a code. A code, you know, whether I had Lebanese black or Afghan green (dope). Whether I was out or in, whatever."

"The raid itself was really funny. They came In first of all through 159 (Railton) and I was in 157. So they went all the way through 159 and into the garden and I heard all this commotion. I was actually in my room sewing a frock. I was in me knickers sewing a frock. They came to the front door. Somebody came to the front door. I was thinking I'd better finish that seam. I opened the door and it was the police. I shut the door and behind me there was another policeman coming up. He said "We're the police!" and I said "Oh". So I pulled the door open, right, and got the back of this policeman and said "There's some of your friends through here". I pushed him through and shut the door behind him."

"I thought, what the fuck's going on here, holding this door and pushing it back. Then this other policeman comes up the corridor and I thought, well I suppose you all better come in then. Then they found three rather dilapidated dope plants at the top of the house somewhere…I think on our roof...I told them I had to go and get a frock and some lipstick so they escorted me back in to get a frock and lipstick and they pulled us all into the kitchen at 159. They said - look at least one of you has got to take the rap for these plants. So sod it. Originally we were going to say we were all responsible. Fourteen people altogether. But the problem is one or two of us had suspended sentences for other things. We were a bit frightened because some of us might have been classed as illegal immigrants. So if they had charged all of us with it that would have all come out and we would have got done very disproportionately. So Petal turned around and said "I grew the plant". We actually decided at the police station that Petal was going to cop for it. That's effectively is how that happened. As far as I know."

5. Squats, Squalor and a Disagreement

(a) "I remember having a row with Terry Stewart....Terry and l broke in to 155 (Railton Road). That was where he ended up living wasn't it. Then afterwards he turned round and said: "Oh no this is for me" after I had ended up cracking it (with him). That's when I went and cracked 149 (Railton)"

"I remember opening up 149 myself. It had all the windows smashed. They'd boarded it and shoved all the windows through. I spent two or three months wandering around and putting in....working like a Trojan....stealing windows from other houses and putting them back in. I carpeted the place all the way through and put in plumbing and electricity because it all needed doing. I was actually very proud of that house. I spent a fuck of a lot of effort and time and the rest on it."

(b) "143 (Railton) was where Colm (Clifford) ended up living with Derek Cohen. That was the last house to be squatted. I remember crawling across an awful lot of rooftops when we were opening up those houses and going through skylights. One house we opened up, we looked though the skylight and there were people still there (cry of horror). Now the house that Jim (Ennis) ended up in, 153 (Railton), that is the house we went into where there was the most amazing card on the mantlepiece. The house female impersonators in Las Vegas: "Dear Peggy, having a fabulous time here." It has this sort of yellowing....oh yes, definitely us (laughter). This is definitely the place for us."

"The whole thing about some of the houses on the rest of the street was that some of them were effectively being decanted of single people tenants at the end of the Rachman era weren't they in effect. Remember the electricity in 153 being condemned? It was all still bakelite switches. That's the reason why they were decanting the tenants out who were mainly elderly Afro-Caribbean gentlemanly men. They couldn't give it to a family."

-

On Childhood and Coming Out

"...childhood is not a time when you live is it...childhood is a time that you get through, you know, and when you actually leave the maternal home you don't actually start living until you are living with other gay people. Anything else is just biding time, isn't it. Living with other gay people is an integral part of coming out. I don't think anyone can say that they have come out until they have lived in a non-parodying of heterosexual relationships situation with other gay people. Really, I think that is one of the pointers towards whether a person has come out or not."

On Radical Drag

When asked by Bill Thornycroft about dragging up to go to dances Julian was emphatic that the people at the Gay Centre and gay squats had very little understanding of what radical drag actually meant:

"No, those people didn't know what drag was Bill. None of them had realised it. None of them. My god. No, no, no, no. I mean to say as far as I was concerned when I moved into Brixton the only drag that had gone on before that was Colm Clifford dragging up for the General Election and through fault or design ending up as a parody of the conservative candidate (Brenda Hancock).

"But as far as I was concerned when I first moved in that was all I knew or heard of. Suddenly I became the arbiter of what it was all about. A role up until that time Alistair (Kerr) had actually held. The role of the arbiter of what radical drag was all about and I thought to myself, yes, it has to do with the exploration of self and the exploration of self-image and the way one is related to in how you dress. Constantly and consequently for an awful lot of the time I sat on a sewing machine."

"You know I was constantly asked to give definitions of what drag was all about and what radical feminism was all about as applies to men etcetera. Quite frankly it is something I was sick of then and I am sick of now. lf you wear clothes of the opposite sex and are described as the opposite sex what you are playing with is the way that you are desired. As far as I am concerned that's a very private thing. Looking at the way you are desired is basically about....what area of sexuality you want to put yourself into."

"Unfortunately an awful lot of the people who lived in Brixton immediately thought that dressing up in women's clothing meant that you wanted a real man. That you were all girls together. I think that, as far as I'm concerned, is something I think the whole of the feminist movement hasn't learned yet. That men dressing up in drag is not to do with who you desire. It is to do with how you wish to be desired and the two are very different things. it is not sufficient to say that if you dress up in high heel shoes and a tight skirt that you want a man. The gay men's movement, that are anti-drag and haven't clicked onto it yet, will say that means you want a real man. That you want the GI Joe."

"The women's movement will say that what you want to be is an oppressed 50s WASP and neither is true. What dressing up like that actually means is not that you want to be at one with your body but that - number one - you want to have matching accessories. If you are going to wear high heels and a skirt or the kind of skirt that determines that you have got to wear high heels - that number one, you want a certain sort of look. Number two - you want to be a desired person. The two are very, very different and to actually say, as the feminist movement would say, that this is the only way that you can be a desired person, then that's wrong. What they can't disassociate is that this is not the only way you can become a desired person. This is what you are wearing for those ten minutes or that hour or that evening. There is a whole wider range to what you are into."

"What you are doing at the moment is you are playing with the role. It is very interesting that one party I went to with Don Milligan, Jim (Ennis) who was dressed completely in those sort of clothes, you know tight skirt, high heel shoes, 50s WASP beehive. The attitude from many there was 'this is disgusting. You are reminding us of an oppressed woman.' Don Milligan turned round and in not so many words said 'Well, you lot in all your dungarees remind me of oppressed men.' Indeed why is it all right for the slaves to wear the clothes of the Master but not all right for the Masters to wear the clothes of the slaves. That's true to a certain extent. But It isn't all right for the Masters to wear the clothes of the slaves when they do it for fun. You know, like the Berkeley Ball Hop where everybody comes as peasants and yokels. But when we come to talk about people, that person's exploration of themselves, to do with the clothes that they wear, there is a big difference. The person is not always political but politics is always personal. The two are not two sides of the equation. One does not mean the other all the time as far as I'm concerned."

"At the GLF dances at Brixton Town Hall I was always expected to do things. I was always expected to be dressed. I regret that. I mean to say, in the same way as gay pride parades, I was always expected to cut a figure, to cut a dash. Quite frankly I find it boring. I am always supposed to be the spirit of radical drag. I think to myself why hasn't everybody Iearned yet that all they have to do is...on the morning of the march (gay pride etc.) wake up and think like, I'm taking down the curtains and, you know, I'm going to use an awful lot of pins. Just get there and end up as I have on two gay pride marches - naked (laughter) where it has all clattered down around my ankles. I stood there completely and absolutely naked. You know, like the pansies have bloomed...it's just a question of letting your naked self wander along the street and that's what marches are all about. That's what being out an gay Is all about. it's letting your naked self walk along the street. It's not about a show of virility even if that virility is encased in...the loons that you were wearing yesterday and a pair of sandals."