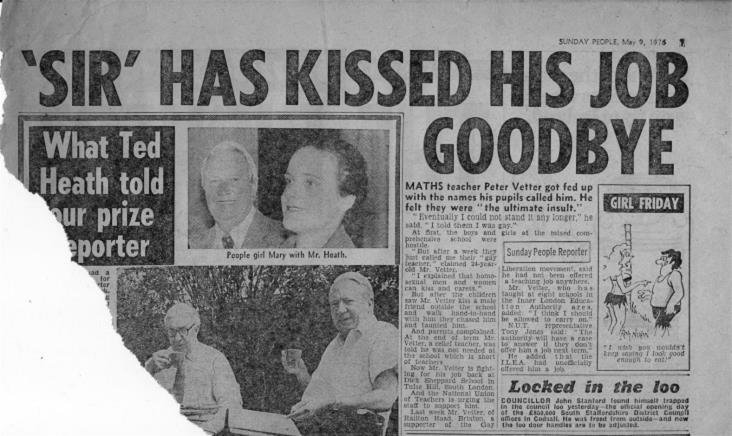

Peter Vetter

Interviewed by Bill Thornycroft in the early 1980s and Ian Townson on 21st April 1969

You can read more of Peter’s memories of the Gay Centre here

Peter Vetter was born in I951 and spent his childhood and early adulthood in a rural town in Queensland, Australia. He was educated by catholic nuns up to the age of fourteen and he came from a fairly liberal family background with his parents voting against the far right politician Bjelke-Petersen. He became involved in the anti-Vietnam war movement at university.

He arrived in London in about February I974 after two years as a teacher in Australia and stayed in a hotel in Paddington. On his first day there he saw an advertisement in a newspaper for Gay Switchboard and on making a phone call, for the first time, he nervously stammered out the fact that he was homosexual. He was given details about the a gay disco at the Prince Albert pub. Within three or four days of being in London he plucked up courage and went there where he met Peter Bradley and went back to his squat in Elgin Avenue.

-

“It was fairly confusing and I was a real country boy. London just seemed unbelievably filthy. Everything just seemed incredibly dirty and when I arrived in this squat it confirmed all of my worst horrors about what it meant to be coming out as gay. Like I was getting something incredibly sordid. There was a real contrast between that and the pleasure I was having in this place. I think I gave Peter Bradley a really hard time. I think he got fed up with a lot of my self-oppression I felt about being gay. What I felt about that I think I really dumped onto him. There weren't many bars at the time. There was the Prince Albert, the Coleherne and the Salisbury."

"I didn’t live at Elgin Avenue. After leaving this hotel I moved into a room in a house in Willesden Green. I didn’t stay there for very long either. I think I moved in with Peter Bradley because I spent a lot of time there anyway so I practically lived there. That was a squat that they were evicting. It was a big eviction at Elgin Avenue. Quite famous with television cameras etc. There was a curfew on the place. We used to have to get back to the flat by about one o’clock at night through these corrugated iron gates. Everyone was getting ready for the eviction. Filling large custard cans with ashes that could be thrown at bailiffs."

"There was quite a battle on the day involving some of the people in the squatting movement of the day....Piers Corbyn (bother of Jeremy Corbyn, ex Labour Party leader)....he was living in Elgin Avenue as well. So in the end it was like a kind of siege. At the very last moment we were all given places in Camberwell and the whole place was decanted after we had come to some agreement. We ended up in Rust Square, Camberwell. It was unbelievable. They had moved us into these places that had no electricity. They were literally crawling with rats. I was teaching at the time and I remember going into school several times and finding my trousers covered in candle wax because we had no electricity. That was Vauxhall Manor School which has now closed down."

-

"On arriving at I59 Railton Road I met Jamie looking for some aruldite to stick his teeth back which was disastrous. I lived with Derek Cohen and Hans Klabbers at 106 Mayall Road plus a guy called Michael Jackson, a friend of Derek’s. I lived with Ernst Fischer for a while."

"Jamie Hall and Colm Clifford seemed to epitomise the different approaches. I think for me they represented more than anyone the personal and the more overtly political. I was having a relationship with both of them at the same time which was a bit tricky. I was a little bit caught in the middle and I didn’t have any definite theories; definite ideas about things that I was able to articulate in the way that other people seem to. I don’t know whether it was because I was a foreigner. I always felt as though I was never quite as involved in the same way. Even though Colm was Irish he seemed to have a much better command of things. He seemed to know what was going on. I think that was one of the dilemmas for me. I think I should have known more because I was from vaguely English/Irish stock but in fact had grown up in a country that was totally different. I wasn’t really particularly involved in politics there either. I tended to keep out of those discussions. I remember going to zaps and playing around with drag and make-up but I wasn’t particularly interested in theory. Double F magazine(?)."

"I remember at the time all these journals coming in from America and I was not particularly interested in them. This seemed to be something that Jamie was subscribing to. Colm was

involved with Gary (de Vere) and had a much broader political approach to things. I remember all those meetings but I very rarely spoke at them. l was much more interested in getting down to dancing and the disco floor or going to Andreas’ dance classes. He did quite a lot of that. Dance, mime, movement, contact, improvisation kind of things.”

Peter was involved in re-squatting the Gay Centre and doing a lot of re-building work there. He came from a place where machismo was so obvious and he detected elements of that in the way political debates, arguments and scenes were being conducted between people. He believed there were a lot of big egos around at the time and they hid a lot of their insecurities behind argument. That’s the way he saw it at the time. He was aware that there was always a pressure for him to engage whereas others were excused like Robbie (Roberto Campagna - Italian) and "a lot of French people." He partly wanted to be like them: "wild and silly and not really get engaged in the politics of it."

He was very prepared in "a lazy way" to let others do the speaking for him. There were always ‘leaders’ who were better at it than him and more prepared to speak up. But also he believed those leaders were prepared to be pushy and bully people into being involved in things that they weren't really interested in. He saw them as ‘theoreticians’ who hid behind a facade of ‘knowingness’ but were just as insecure as everyone else.

Yet he still believed that everybody’s contribution to the place was vital though they operated in very different ways. But with Gary de Vere and Colm Clifford somehow he was made to feel that he was not ‘measuring up’ all the time. This at a time when he was experiencing difficulties in coming out at school as a teacher.

Opposition to the Gay Centre's application to Lambeth Council for a small grant to cover running costs: Mrs. Old, one of the proprietors of the George pub, having barred gay people from drinking there, attempted to whip up opposition through descriptions of men coming out of the gay centre in wigs and suspenders etc. Instead of being outraged people just laughed and giggled about It.

(L-R) Jamie Hall, Peter Vetter, unknown, Julian Hows, unknown, and David Callow

Peter retold the episode of the police raid for drugs at the houses and Peter Cross’s and Jamie’s arrest. The embarrassment of being discovered in bed by police or sitting around the garden in drag after an event at the Centre when they came swarming over. People had to decide in twenty minutes who would take blame for the dope plants avoiding confessions from those who already had a criminal record and anyone from another country to avoid the risk of deportation.

Peter was not aware of any involvement with black groups. Bruno (de Florence) was the only person he knew of who was involved in the gay community who was black. After the Gay Centre was finally evicted meetings were held at the Womens’ Centre, 207 Railton Road.

-

The transition from his previous heterosexual experiences to this brand new way of relating emotionally and sexually to men, with no road map to follow, led to stresses and strains and failure:

"I remember thinking I had it made when I had a relationship with another man and we moved in to a flat together in Clapham. That was the whole way I was directing our relationship; on a kind of heterosexual model. I was putting a strain on it all the time. I eventually got him to agree to move to Clapham. Of course we were only there for about a week when the whole thing blew up. I was completely desperate. More desperate than I had ever been before because I thought, I’d come out as gay, I'd actually had a relationship with this one person and even that didn’t work."

His relationship with other men at the time were equally strained given his conscience-driven anxiety to remain faithful to Peter Bradley:

"I had met Colm (Clifford) and I think I59 Railton Road had just been opened up (squat). Colm and I had gone to see a movie together. I was having my relationship with Peter Bradley when he was still living in Elgin Avenue. This is before we got 'married' and moved into the Clapham flat. Colm and I were really hot for each other but I was having nothing to do with it because I was having this relationship with Peter Bradley. I was being a responsible homosexual. But it so happened that....I think I had come back from a holiday and I went down to see Colm and I purposefully/accidentally missed the last bus and we had to share the same bed together. I just put Colm through the mill that night because I just wouldn’t have sex with him. So we lay in this bed together with me kind of saying ‘No, no, we mustn’t’. This went on till about 5 o’clock in the morning. I just kept on really wanting to have sex with him and when he stirred to kiss and cuddle me I would push him aside again."

"It was about 5.30 in the morning and the sun was coming up. I hadn’t slept a wink and I felt dreadful. At a 'weak' moment we did it in a rush. That’s exactly what it felt like and it was over. I just felt dreadful. I felt absolutely awful that I had somehow betrayed the relationship with Peter Bradley. It went so much against how I thought I should relate to someone. I went back to Peter Bradley the next morning of course, at 6.30am, and confessed everything. He was somewhat baffled but to a certain extent he went along with it as well. He said it was alright and I felt so guilty about it I was impotent for about a month. I felt so bad about it."

-

"I think there is always an anarchic part of your sexuality that wants to take over. I can remember as a teenager having sex with people. We were all having sex, playing doctors and nurses. Probing each other. Even though it was kids stuff we were actually having real sexual pleasure with all of this...."

"For me it was impossible to take the step from having a heterosexual relationship to a situation where I was having sex with a lot of different men. To maintain some kind of measure of respectability I went through this monogamy stage. I felt I had to be really faithful to make it acceptable in a sense. It’s like the coming out letter to my mother. I felt like it fitted in to some kind of framework of something that she could relate to. I could talk about a man and a relationship and some kind of a life together. With the kind of relationships I have now it’s impossible to write to my mother because it’s no longer at a level she can understand. I think that’s why, when I met these men from Brixton, I felt like there was some kind of chance of exploring that kind of....but again it wasn’t conscious at the time that I thought in those kind of terms. I just really liked them."

It was through Peter' Bradleys friendship with people from the Brixton gay community that he got to meet them:

"I can’t remember how we met them. It may have been at an opera and they were talking about this place where they lived in Brixton. For some reason....oh, I know what it was. I was ill one day. I was feeling really miserable sitting in my Clapham flat. Colm and I think Petal (Peter Cross) and David Callow came around. Even when they arrived there was just something completely different about them. They had been shopping for the community, the commune, I think in North Street at one of those alternative veg and market places. They all looked stunning. That's what struck me about all of them. They all looked incredibly beautiful. The three of them. I remember Colm had this enormous shopping basket which was full of vegetables and things which seemed a million miles away from me feeling ill and dissatisfied living in Clapham. I am sure Peter felt equally miserable."

-

"I moved somewhere else first and then shortly afterwards moved to Brixton. I almost didn’t move to Brixton. It seemed almost an incredible step in a way. I still felt very much like provincial Australia and I remember the very first time I went down to view the houses. I had trouble sleeping so l went down fairly early on a Sunday morning. I rang on the door of 157 Railton Road. I think it was the only other squat that had been opened up at the time. Julian Hows opened the door, completely naked! He said "Darling, don’t you realise this is seven o’clock on Sunday morning". I’d got him out of bed and that really was my introduction to the houses."

On his early visit to the Gay Centre and the first household in which he lived:

"Yes, I had been to the Gay Centre. I think Andreas (Demetriou) was doing a couple of dance classes there. There were those ‘Greek positions’ that one did. There were discos at the Centre and the whole place was expanding really quickly. I was feeling terribly shy.. ..I thought everyone else knew what was going on but I didn’t. This was the first time I had been around gay people engaged in an activity other than sex which was very nice. I just remember that they were incredibly exciting because I have always wanted to be a dancer (laughter). So we were down in this stony cold basement doing Greek positions and it was all very kind of amateurish and wonderful. But I think being there and experiencing the Centre certainly made me kind of very agitated within my relationship with Peter Bradley because it seemed incredibly restricting with the kind of structure we imposed upon ourselves in contrast to what was going on at the Centre because it was early GLF and everything else that went along with it which I am sure has been described...."

"So then I think through Colm Clifford I moved into l59 (Railton Road). I was going to move into I57 but I think Peter Cross and Robbie (Roberto Campagna) were there and they asked Julian Hows to move in instead of me. I was totally freaked out when l moved into the house. When l first moved into l59 here was, I am sure you will never be able to write any of this, there was kind of....Ian Townson was looking super depressed sitting at one of those great tables writing some kind of manifesto document. David had really long hair of course. The place was a complete tip but there was this wonderful smell of baking bread mingled in with cat shit. It was freezing cold. David Callow was sitting on cushions on the floor stroking at least three kittens and asking someone if they had a valium. Next minute the door opened and Jamie Hall appeared with his two front teeth missing and with incredibly long hair. The whole place seemed incredibly scruffy and filthy and dirty afier coming from provincial, clean Australia with lots of space and sunshine. Here I was in grimy Brixton in this commune with all these homosexuals at at time when I was only just coming to identify as being one myself."

Dining Al Fresco. Foreground Terry S, Jane R. Background unknown, Maxime Journiac, Peter Vetter by the window

-

"I mean, for the first three years or so it was just so energising. All that activity is what I had been used to as a kid anyway coming from such a big family. No, I liked all that activity and it always brought in lots of different people from different parts of London. It was almost as though you never had to go out. I think that was one of the drawbacks. I think that’s what made Brixton kind of really insular because there were so many people around. You never ever had to go out. It provided a whole lifestyle. There was companionship and sex, discussion and good food and an endless stream of new faces all under the one roof....it became really cosmopolitan. After about twelve months or more there’d be a knock at the door and anyone could be there. There could be kind of Heidi from Copenhagen saying "Hello. I am from the Gay Movement and I would like a bed for the night" or it would be "Ciaou"."

-

On asked whether he felt set apart from other people because of his ex-heterosexual life:

"No, no, not really. In many ways I had a completely different politics around my heterosexuality. I just decided to forget about it in a way because my relationship with men were just so exciting and powerful at the time that I almost totally forgot about it. Unlike a lot of the other kind of ‘nerds’. The Bi (bisexuals) at the Centre who were pushing for a kind of bisexual politics which is something l never ever identified as being and still don't."

Was he upset at all by the separatist politics:

"Not at all. In fact I was very much a part of establishing that group. There were years when we never ever saw another straight man. No straight man was ever allowed through the front door. There was positive vetting. I came at a time when there weren’t really any straight men around at all. I think there were in the early bits of the squatting period. I thought there were only women around at the time like Pauline (McDonnell?).

-

What happened after the Gay Centre had closed and the tensions among people in the squats:

"I was living at I06 (Mayall Road) and that was quite different. In some ways there were definite changes that happened other than the Gay Centre finishing. Railton Road went on for a long time after that for me. It’s actually quite a complicated and painful area to even begin to talk about because a lot of the changes that happened were about really big divisions among people in the houses. In some ways I don’t feel quite removed enough from it yet to actually work out what happened. Even now I can run into people on the street who won’t actually say hello to me. Who still refuse to say hello to me and I am not exactly sure why. There was certainly this constant feeling of people being betrayed in some sense. But I am not sure if that isn’t just a simplistic answer. Perhaps we had this set of politics defined by GLF and maybe people went beyond them and didn’t keep the pure line. There was a lot of mistrust."

"In a sense we had a community which was incredibly exciting and incredibly insular for a short period of time and it was possible to do that. Very important to do that and there were a lot of people who signed on (drew unemployment benefits). Gradually people went out and got jobs and did start to have relationships with heterosexuals just in their workplaces. It was really difficult to work out where we as individuals stood within the great heterosexual state. I think that was partly what it was. But for a long time we almost declared UDI (Unilateral Declaration of Independence). Things were fine then. But it was impossible to live on the dole and bake bread and maintain that kind of separatism which I think was very important. It was certainly incredibly important for me. When all these other influences started and people did start going out into the straight community more because of work or because of other interests it did put a big strain on the whole community I think."

PV's views on the shift from squatted households to redevelopment into single person flats as members of the gay section of the Brixton Housing Co-operative:

"I don’t particularly like that idea. If you have got a community and it is still being thought of as a community because there is that communal garden and you can’t ignore the history of the place....l would have thought that to build any kind of flexibility into it as a project there should he at least one house....making it all into self-contained units to me seems to be a little bizarre. Really inflexible because it doesn’t allow for any kind of change. At the moment I live in my own unit here and I share a toilet and a stairway but it’s not a situation I see myself living in forever. If I did have some kind of control over the design and architecture of a whole area I would try and build in some kind of flexibility like that. It seems to me that living by yourself is part of the regression of living in the 80s as much as anything. I didn’t think the whole thing was going to be turned in to individual flats. I thought there were houses that were going to be left as houses (i.e. communal)."

"But you see, I think....what happened in Brixton during those days wasn’t something that was planned. It was, as Truffaut would say, an 'event sociological'. We used the kind of structures and buildings that were there....and they were structured for family units....we totally changed them simply by....I mean, there was two households that wanted to be large, which was 157/I59 (Railton Road), and we just knocked a hole through the wall. We had a kitchen in one house and a bathroom in the other and it became this great big living space. I don’t see any reason why, though I haven’t seen the plans for the places, why this couldn’t be done with the houses. I don’t think you can actually plan an event like Brixton so I don’t think you can actually plan an architecture for it. In many ways there were times when it was as communal as communal could be given the structure that we had. That has a lot to do with it. I mean, there were a lot of other things than the area of sexual politics that we challenged within Brixton. That was around privatisation of space and property and things."

The problem around communal living and its encroachments on individuality:

"One of the big dangers within big communal structures or co-ops is that you lose yourself to this wider theme. I always think that it is important that you keep some sense of privateness, of your individuality, which people did in their rooms. If you looked at peoples’ rooms in Brixton you could almost have an exhibition on the types of rooms people had. I mean there were some attempts way, way back in the beginning to even have communal bedrooms which I am very pleased to say were opposed. You wouldn’t have been able to have all that intrigue of popping in and out of each others beds if there were communal bedrooms."

-

"I never really related to teaching as my profession. It was just something that I did to earn money basically. Okay. Well I was doing supply teaching at the time. I was one of the few people who was working as I Remember. I was really paranoid about signing on (claiming unemployment benefit) being a foreigner. Also l had this thing about working. I wasn’t going to be a bludger (scrounger) on the state. So I always worked. It was kind of like enthusiasm really. When I kind of watch those mad New Wave Christians I relate to that kind of enthusiasm, that kind of high. It was a time when I had got a real rush of energy. That real joy of life feeling that was very much energising when I moved into Brixton and it was inevitable I think that would affect the way that I felt in my work because....more and more I couldn’t tolerate the blandness of my work situation. It was a mixture of the two. It was the blandness of the work situation. The way the teachers dressed and the layout of the classroom and the staffroom. Just the rigid order of everything. In the meantime at home everything was incredibly exciting. Everything was being questioned from my own personal sexuality to the order of the house to whether or not you had a do on the bog or not (cleaned the toilet?). The school just seemed like this great dampener on my life."

At school were you still presumed to be heterosexual?

"Of course, darling. Yes I was. I didn’t even feel as though I had made a decision to come out. It was just that more and more of this enthusiasm and craziness began to affect me as I went into school. The way that it came up is that I went in one day after a session of nail varnishing. I think I had some nail vanish on my fingers and l probably had a bit of mascara left over from the night before. Something l had done at the Gay Centre. So in that sense it came up very naturally in school. It just seemed very easy to talk about it. It didn’t seem at all difficult because I knew that I would get support. Well, that’s too cliched a word....It was more about spontaneity in a way. Now l think it would have to be a decision to come out in a certain situation."

"That’s the difference I think between now and then. Not that I felt there was much support there but that it was something I felt very easy and spontaneous to do. Now I feel I would have to make a decision like, have I got the support at home etc. etc. Then it was just like a part of a whole thing that was happening. It was this great thing that was moving along and coming out at work was just another part of it. The context of the Brixton community was very important at the time. I mean we had coming out parties. Coming out at work parties at the Centre."

"....the school I was teaching at was only half a mile away (from the Centre). A lot of the kids that went to the school lived on Railton Road and they would often see us strolling into the Centre or walking back to the house holding hands or getting ready for some demo or something like that."

"....the first time it was ever spoken about at Dick Sheppard (girls' school) is when I had gone in with varnish on. Some tacky nail varnish on. I think l spoke to a class then and told them I was gay. It moved around very slowly at first. It was about a week and a half before kids had heard from other kids. But the thing that really made the whole school know about it was when I met Colm outside the front of the school just as everybody was leaving. There were about a thousand students there at the time. All of them were streaming out of the school when Colm came up to meet me. We gave each other a peck on the cheek which was the custom at the time. Meeting your (gay) brother in the street. It was almost a law that you greeted him with a kiss."

"There was an absolute uproar. That’s when all the staff knew about it and all the kids knew about it. It came up at a staff meeting because some really homophobic teacher was saying that the traffic was stopped and the buses had to stop on the road because there were about five hundred students surrounding us. Asking us questions and screaming. Yes, she was claiming that we had stopped the traffic and that someone has almost been killed by this incident. I toned it down a little by which time it was too late and I was having discussions in the corridor during the lunch breaks. That was really exciting and I think that was the time when I really enjoyed teaching most of all."

"....I went and saw the headmistress about it. I walked in and I said "Ms Brody", I forget what here name was now. I said "Ms Brody" because I was really hyped up from this discussion I had had with these fourth years. I said ‘I am homosexual’ and she reeled back in the chair and her two dogs went mad. They sensed her fright and immediately started running round and round her office yapping madly. She being a proper diplomat hid the shock, sat down, took a deep breath and kind of said "Yes, Mr. Vetter.""

"....It was wonderful actually. She said "Well, as long es you are prepared to take a little bit of flack" something like that. But then her tune really changed. I am not really sure why that was. I think she probably just couldn’t really cope with it. Certainly none of the parents had complained. I think now, looking back on it, a number of teachers had complained. A petition was got together at the time when they were trying to get rid of me. It was left in the staff room and was signed by about ninety per cent of the teachers for them to have me back again after half term. Because I was a supply teacher I was very vulnerable to renewal of the contract. It was actually stolen. Her solution was just to make me redundant at half term and not have me back again. She was supported by the Divisional Office. This petition disappeared."

The school children’s' reaction to him coming out:

"...Well, on the whole, basically, they were just craving information. That’s the general thing. Even if their reaction was hostile or friendly the thing that stood out was that they actually knew absolutely nothing about it. They were fascinated about it because they had got a snippet of information and, you know, sexuality is always fascinating to kids. They were all girls. Some of them weren’t exactly kids either.....They would just turn up in their hundreds at break time. I'd decided not to talk about it in the class because John Warburton had been got by ILEA (Inner London Education Authority) because he had actually spoken about it during class time. That was one of the excuses they used against him. I was determined that I wasn’t going to get caught in the same way. That they couldn’t use the same excuse. I was determined that they would have to actually come out with the homophobia rather than hide behind some ridiculous ruling. So as soon as I walked into a classroom they (the students) would say "Oh, Mr. Vetter. You are a funny one aren’t you." I would say "Yes I am. But we’re not going to talk about it until break. You’ll have to wait until then." Then we’d chat about it and all their chums would come in because they would all be out there. You could see them looking through the doors. They had those wooden doors with glass bits in it. They could see where I was and they would have all their friends there. Then we would have this symposium on homosexuality during ten minute change overs."

"....I only had one really unpleasant experience which was with one girl who I think was in the fifth form. She kept on running in and leaping on a table when we were talking and screaming at me that it was us white folk who had perverted the blacks because someone had asked me....it was about eighty per cent black girls at this school....one of the girls had asked me if there were any black gays. I said "Yes, of course." This woman was really hostile and angry about it because she couldn’t cope with it. But they were very supportive on the whole. In fact I was told by a student who I saw after I had left that they all went on strike and refused to go to lessons. I remember....what was her name. Was it Maggie? The girl who came into the community. I think I taught her maths. She was saying that they all refused to go to their classes because l had been got rid of. For a time anyway. It’s all so long ago now."

How did this affect his future employment prospects as a teacher?

"It was almost impossible to get work in Lambeth. They put me into junior (primary?) schools. There just weren't any placements with older kids. I went to East London after being warned by the inspector there that if I did anything....It was quite funny. I was aware that I was trying to be muffled and I disliked teaching more and more after that I think. They’d obviously got information from Division Nine that I’d taught in before that I was gay. He warned me that if I was had up for any offence I really couldn’t teach. Warning me about cottaging and molesting young boys."

On asked whether he came out at subsequent schools:

"Yes, I did. In a different kind of way actually because it was effective that they had put me into junior schools. I found it very difficult to work out how to talk about sexuality with really young kids. I just used to wear really outrageous....I just used to try and challenge the whole concept of masculinity anyway. I used to wear this great big wonderful star, diamante earring. My hair was quite long. All the little boys used to play with my earring. It was about twice the size of a 50p piece. I had these very nice butterfly bobby pins that I would wear in my hair....and you know, they thought, there was obviously something cuckoo about this guy. I did talk to the older kids in the junior schools. I suppose coming out in secondary schools did make me aware that there are all sorts of ways that you could subvert the whole idea of masculinity and femininity anyway without saying that you are homosexual. But I wasn’t very happy about being moved down to junior (primary?) schools. I was actually beginning to enjoy teaching Maths in Seconday school at Dick Sheppard. So I eventually stopped teaching."

-

PV's views on 'class' the subject of which was never really approached in the community:

"I'll say a few words about class then. I feel something should be said about class in Brixton because to me one idea that was spoken about at the time was that our sexuality cut across race and cut across class and that it was this great unifying theme that united....you know, that cut across nations because Brixton was composed of a lot of Australians and Irish and Continentals and English. There weren’t many blacks there... Bruno (de Florence). There was this idea that we cut across all these barriers and I don't actually think that was the case. What we tended to do was ignore a lot of those issues."

On Gay Men's Week retreat at Laurieston Hall (explain). Some felt it was a 'cop out' by replacing 'real' urban struggles against oppression with individual self-development in a remote country retreat:

"The split in the community between people who thought that all the struggles should be worked out in the city. You want my views on it. I think that was the time when the big splits started wasn’t it. I mean I think that was probably a real important event."

"I wasn’t very much aware of it at the time. I couldn’t work out why so very few came from Brixton (to Laurieston). It was only in a conversation with Ian Townson who said that the struggle was all in the city and it was ridiculous to go all the way up into this country retreat and eat oak leaves. I’d agree with him about the oak leaves."

"I think it’s just, you know, with any oppressed group you just get incredible amounts of internal splits and bickerings. I think it is a lot to do with the fact that you are an oppressed group to start with. It’s too simple to talk about one lot feeling like being into personal change was important and another lot thinking about wider things. It seemed as though that is what it was all about at one time. That us 'brown rice' lot were getting into co-counselling...it seems that it was all down to the contradictory basis on which Gay Liberation was established anyway which was the personal is political."

"For myself l really felt battered by the whole thing of coming out at work. I did find that really exhausting; all that upfront, out there, Left kind of politics approach. I wondered where it had actually gotten me. I knew it was very important in terms of...that there was now visibly a group of gay men around but I felt a little bit exhausted by it. It didn’t answer any of the questions....well, they still haven’t been answered."

"Of course we exaggerated. That was the whole way everyone approached politics there. Everybody exaggerated the stances that others had made. So while we were kind of narked about the brown rice label there is a sign on the walls in Brixton which I think sums up a lot of the way that the group responded: ‘They exaggerate their forms of outrage’. It’s written there. I really think that’s how the two sides kind of responded to each other. Because that approach was disapproved of slightly we became more and more split until basically the brown rice lot and the others had absolutely no communication between each other at all. Originally before the Centre broke up it was everybody against this group of people who identified as bisexual, the nerds. Then it just became more and more split."

The splits were partly healed by coming together later on wider issues such as the Gay News Defence Committee, CHE (Campaign for Homosexual Equality) Conferences and various demonstrations and campaigns. Also involvement in organising the 1976 Gay Pride Week.

-

On the question of women living in the houses:

"Yes. Jan and Rosemary lived there for quite some time (159 Railton Road). It made quite a difference. Some gay, some not. Then Sandra Cross lived there for a while (Peter Cross's Sister). The whole community seemed to be separatist in terms of heterosexual men. There was almost never any straight men coming to the house. Then only as highly vetted visitors and that applied throughout the whole community. Then women visited the place and stayed there. After Jan and rosemary there weren’t any gay women living there until Anna Duhig came back again. There was Maggie living across the road (146 Mayall?) at one time. There was unease about women living in the community for various reasons (unstated)."

Having moved away from the community and returned what changes had occurred. Was there still a gay community that he felt part of:

"I came back to Mayall Road (106) to live with Derek (Cohen). There was obviously still a group of gay people living there but I didn’t feel a part of it. It was very reassuring knowing they were there but I don't think I even visited anymore. Occasionally I would see Andreas (Demetriou) but I was very busy at college."

Rebuilding tables and benches at the Gay Centre after the first eviction gave PV a life-long set of skills allowing him to eventually set up a furniture making business that thrives to this very day with his long-time partner Fabrizio:

"I had not done anything like that before. I think that is when I launched into furniture making. The fucking Gay Centre! Launched me on a new career. Yes. I picked up a lot of skills around that time. Because it was squatting.....people were learning a lot of things about make-up, electricity, plumbing, sewing, cooking. I learnt all those things."

"I still have an incredible nostalgia about it somehow. As if it was a very important time for me. I almost felt I grew up there in a way. I kind of had my childhood all over again. That was one of the wonderful things about Brixton. I felt like I could play. I tend to be serious. I still get very nostalgic about it at times. But I see it as very much something that is in the past which was creative but can’t be recreated."