To wade through the complexities of how gay men lived and loved together in the squats is a daunting task. Unlike 'straight' society there was no ready-made mapped out direction to follow that would allow easy cohabitation or collective living arrangements to flourish. Sailing through uncharted territory by a group of disparate and sometimes desperate gay men experimenting with new ways of living was problematic yet in many ways productive and of positive value in unpredictable ways. How did we judge who lived where and with whom. What where domestic arrangements like regarding unpaid housework, cooking, cleaning, shopping, maintenance work, gardening. How problematic were political and cultural differences of nationality, race, class, ethnicity and gender. Did we care for each other or did we feather our own nests. What money did we have to live on and how was it distributed. Let's start at the beginning.

The South London Gay Community Centre acted as a magnet attracting an increasing number of mostly gay men into the area. At its height the Gay 'Community' comprised of about ten to twelve squatted houses that had been judged unfit for family habitation. Many had been left empty as people were moved out of decaying slums to better accommodation. The area was also blighted by much-delayed then abandoned housing redevelopment schemes in and around the Railton Road area leaving properties to deteriorate even further. The squats included 143 to 159 Railton Road back to back with 146, 148 and 152 Mayall Road with eventually, over time, the creation of a shared garden between most of them.

It has to be said that some squats were transient while others became permanent. The walls of each separate garden were demolished to claim a space for all to use and enjoy against private individual plots of land attached to each house. Pathways were laid out, flowers, shrubs and trees were planted and cultivated and back doors were left unlocked for free access. The kitchens often became a 'house within a house' where people met, made home made bread and consume pots of stew with brown rice amid conversations ranging from gossip to political discussions to the planning of future campaigns. A spliff or a joint or two of marijuana or cannabis would on occasion pleasantly muddle up time and space and the decision making process as would cakes laced with the divine weed.

People arrived at the squats for many different reasons. Some where desperately fleeing from oppressive situations in their lives or from homelessness. Others were glad to find the company of unashamedly 'out' gay people rather than remain confused, isolated and lonely. More politicised gay people saw this as an opportunity to attack 'straight' society through adopting an alternative lifestyle that challenged the prevailing norms of the 'patriarchal' nuclear family and private property. Others simply found it a cheap way to live with like minded people. Notionally everything was shared in common, including sex partners, and gender bending was encouraged to dissolve rigid, socially imposed categories of masculine men and feminine women. For others radical drag was a sheer pleasure and an opportunity for ingenious creativity and invention as well as gender bending.

Besides more fixed residents, many of whom were a cosmopolitan mix including people from Australia and Ireland, the squats gained a global reputation with what seemed like a constant flow of visitors from the USA, France, Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands. Some were transient and stayed for a short time others remained for months or years as residents and lovers. The squats were inhabited overwhelmingly by gay men with lesbians preferring to be with other women and wary of a male-centred living situation, politics and unacknowledged male chauvinism. There were occasional visits from heterosexual women either as friends or relatives of the squatters.

click on the arrows to scroll through the images below

-

159 Railton Road was one of the earliest buildings to have been squatted. It may have been the first one. It was either a smart move or good luck being one of the relatively well 'appointed' squats. Situated in a area of late Victorian and Edwardian terraced houses this dwelling was in a reasonable condition. Containing a small cellar complete with coal chute, a large front room, a smaller eating room and large kitchen, an attic and three bedrooms the stage was set for the growth of communal gay housing in the area. Both internal and external factors worked against this being anything but a smooth process.

Initially there hardly seemed to be any problems about who lived in the houses. With a fairly easy going attitude towards occupancy people would turn up through contact with the gay centre or meeting other gay people in the know about the squats or personal contacts of those already living there. The vetting procedures was non-existent though that changed later as people became more discriminating about who they chose to live with.

The first difficulties to be negotiated on squatting a building, after changing the locks to secure occupancy, consisted of connecting up and switching on all the services. Often done surreptitiously without the prior agreement of each utility provider some squatters felt it prudent to register with the local gas, electricity and water boards (as they were then) to pay the bills. The next stage would be to offer a payment of rent and rates (community charge) to Lambeth Council's Housing department or to make other arrangements if the house was privately owned. This would entail the risk of either being accepted as a tenant or hastening eviction proceedings depending on the skill of the negotiators and the disposition towards squatters of the private owners and local authorities. It has to be said that the more wrecked houses had missing windows, leaking roofs and rotting floorboards which burdened the occupiers with the enormous task of fixing it all up.

Technically to switch on the services without first registering as a bona fide customer could have led to criminal charges of stealing electricity or gas. In practice however if approached by a squatting group or one or two insistent individuals who were capable of forceful arguments the utility suppliers were content to register the services in someone's name. Clearly it was better to have paying customers than not.

Occasionally the non-payment of bills, through poverty or laxity in paying them, workmen would be sent to the houses to dig up the road outside. These attempts to cut off fuel and water supplies prompted a fight back from local squatters who would demonstrate outside the offices of the various utility suppliers and occupy their premises. John Lloyd has distinct memories of a more direct action approach to hindering efforts to cut off gas and electricity supplies. Once the workmen had begun to excavate a hole outside one of the houses squatters in the area would be alerted to their presence. A phone tree was activated and it became possible within a relatively short time span to gather together others in opposition to the threat of disconnection. If the workmen could not be persuaded to abandon their digging a simple tactic was adopted. When they stopped either for lunch or a tea break several people would jump into the hole in the ground and occupy it to prevent disconnection of services. The response from the workmen was mixed. Some simply shrugged their shoulders indifferently and went away while others were fairly sympathetic to the squatters demands. Hostility was rarely experienced.

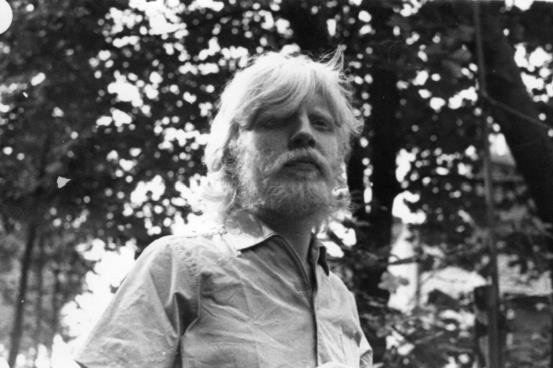

Tony Smith is his room on the top floor.

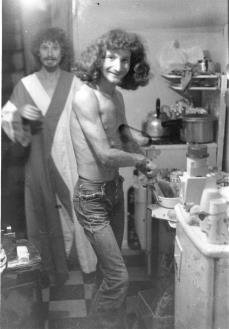

Don Tyler striding out of the basement Kitchen at 146 Mayall Road which opened directly onto the shared garden

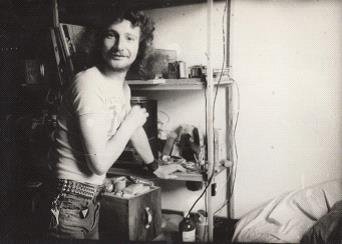

Alastair K and Tony S in the shared basement kitchen

Anna Duhig, resident of 146 Mayall Road

-

With the squatting of 146 Mayall Road, situated across the back gardens almost diagonally opposite 159 Railton Road, external problems began to be experienced. The house had a large basement kitchen. On the ground floor there was a large front and back room and on the first floor a toilet, bathroom and small bedroom. On the second floor there was a large bed room at the front and a smaller one immediately behind. The attic gave easy access to the rooftops of several adjoining houses. The house at first only had one occupant - Anna Duhig. Shortly after squatting the building people would tum up at odd times in the night and speak cryptically of their reasons for calling at the house and sheepishly about the people they wished to speak to. Anna had to keep assuring the callers that the people they were seeking no longer lived there and that she was the sole tenant. Suddenly one night without warning two men knocked on the door and entered the house. Anna was threatened told to leave the house or something far worse would happen to her.

This prompted speculation among the rest of us as to what precisely was happening. After a full discussion of Anna's problems our guess work concluded that the callers at the house were dependent on drugs and that the two men who tried to intimidate Anna were drug dealers. It was assumed that the house must have been their pick up point and had previously been squatted for that particular purpose.

I moved into 146 Mayall Road which meant that at least another person was there but Anna never experienced a repetition of the previous trouble and all went well. That is apart from the fact that Anna and I were incompatible as joint tenants and after a brief discussion between Colm, Gary, Alistair, Anna and myself I decided to look elsewhere for a place to live. I suspect Anna's fiercely independent nature and desire to live by her own rules meant that she did not wish to live with someone else. Also there were tentative plans to have an all-women household. Later the squat was occupied at various times by John Lloyd, Alastair Kerr, Tony Smith, Steve Ewart (Craftman) and Michael King.

-

Back at the gay centre the search was on for another squat to crack open. I discovered Debbie who in those days was described as a pre-operative transsexual (woman) the assumption being made that an operation was necessary. She had been introduced to the gay centre through the radical gay counselling group Icebreakers and was looking for a place to live. Number 50 Railton Road was lying empty. The locks were changed and Debbie joined me later. In those days health care for transgender people was non-existent on the NHS and to gain gender affirming treatment extraordinary measures had to be taken including, in Debbie's case, the possibility of having to travel to Casablanca!

50 Railton Road is a corner house with one side facing on to Jelf Road further down from the gay centre towards Coldharbour Lane and some distance from the gay squats. Before Debbie moved in with me I have clear memories of spending a night there lying on a mattress on bare floorboards trying to enjoy a sexual encounter with a male friend. Unfortunately the crashing of bottles on the pavement outside and the shouts and taunts of what seemed to be fights breaking out and a glaring orange glow from street lamps flooding in through curtainless windows worked against full enjoyment of the situation. The walls were so thin that it felt like the fighting was downstairs in the hallway or the kitchen with the immediate prospects of it carrying on upstairs into the bedroom. The atmosphere of palpable menace reduced dramatically the desire for prolonged pleasure and an unsatisfying quickie was all that could be tolerated. The house was situated just at the point were a long line of decaying buildings stretched along Railton Road housing illicit blues parties, drinking clubs, shebeens and a very lively street culture.

When Debbie arrived later we both stood downstairs in the middle of empty rooms with the dim light of the kitchen filtering through into the hallway and orange light streaming from lamp posts through the windows. Once again we heard the crash and crunch of breaking glass accompanied by shouts of anger and triumph. This time the bottles did not land on pavements nor were the people outside throwing them at each other or the police vans as they sped along the street. They were throwing them at our squat.

Debbie and I fled to the relative safety of the gay centre nearby. ‘Battymen’ (insulting Jamaican patois for homosexuals) and transgender people were clearly not welcome at number 50 Railton Road and in a flurry of fear and bewilderment we decided to squat elsewhere.

-

Peter Vetter almost didn’t move to Brixton:

“It seemed almost an incredible step in a way. I still felt very much like provincial Australia and I remember the very first time I went down to view the houses. I had trouble sleeping so l went down fairly early on a Sunday morning. I rang on the door of 157 Railton Road. I think it was the only other squat that had been opened up at the time. Julian Hows opened the door, completely naked! He said "Darling, don’t you realise this is seven o’clock on Sunday morning". I’d got him out of bed and that really was my introduction to the houses."

initial description of the inhabitants of 159 Railton Road and the atmosphere in which we lived strikes the right note from someone who had not long arrived from the wide-open spaces of rural Australia with clean air and space to roam freely and easily. The culture shock of moving into a battered inner city area where people occupied 'cramped' living spaces could only have added to the challenge to tough it out though eventually he stayed for several years:

"So when I think it through Colm Clifford and I moved into l59 (Railton Road). I was going to move into I57 but I think Peter Cross and Robbie (Roberto Campagna) were there and they asked Julian Hows to move in instead of me. I was totally freaked out when l moved into the house. When l first moved into l59 here was, I am sure you will never be able to write any of this, there was kind of....someone was looking super depressed sitting at one of those great tables writing some kind of manifesto document. David (Callow) had really long hair of course. The place was a complete tip but there was this wonderful smell of baking bread mingled in with cat shit. It was freezing cold. Another person was sitting on cushions on the floor stroking at least three kittens and asking someone if they had a valium. Next minute the door opened and another man appeared with his two front teeth missing and with incredibly long hair. He was looking for some aruldite to stick his teeth in which was disastrous.

The whole place seemed incredibly scruffy and filthy and dirty afier coming from provincial, clean Australia with lots of space and sunshine. Here I was in grimy Brixton in this commune with all these homosexuals at time when I was only just coming to identify as being one myself. I also lived with Derek Cohen and Hans Klabbers at 106 Mayall Road plus a guy called Mike Jackson. I lived with Ernst Fischer for a while."

Despite these first impressions Peter stayed for years and found it a positive experience:

“I mean, for the first three years or so it was just so energising. All that activity is what I had been used to as a kid anyway coming from such abig family. No, I liked all that activity and it always brought in lots of different people from different parts of London. It was almost as though you never had to go out. I think that was one of the drawbacks. I think that’s what made Brixton kind of really insular because there were so many people around. You never ever had to go out. It provided a whole lifestyle. There was companionship and sex, discussion and good food and an endless stream of new faces all under the one roof....it became really cosmopolitan. After about twelve months or more there’d be a knock at the door and anyone could be there. There could be kind of Heidi from Copenhagen saying "Hello. I am from the Gay Movement and I would like a bed for the night" or it would be "Ciao". ....we always liked to think that it was incredibly famous but I am not quite sure how it was. I suppose it was just about contacts and a lot of people just did know about it. There were so many people there one summer that we decided that we just couldn’t cope with any more. Germans or Italians or French arriving."

On conflicting political perspectives in the squats and his resistance against taking sides:

“Jamie Hall and Colm Clifford seemed to epitomise the different approaches. I think for me they represented more than anyone the personal and the more overtly political. I was having a relationship with both of them at the same time which was a bit tricky. I was a little bit caught in the middle and I didn’t have any definite theories; definite ideas about things that I was able to articulate in the way that other people seem to. I don’t know whether it was because I was a foreigner. I always felt as though I was never quite as involved in the same way. Even though Colm was Irish he seemed to have a much better command of things. He seemed to know what was going on. I think that was one of the dilemmas for me. I think I should have known more because I was from vaguely English/Irish stock but in fact had grown up in a country that was totally different. I wasn’t really particularly involved in politics there either. I tended to keep out of those discussions. I remember going to zaps and playing around with drag and make-up but I wasn’t particularly interested in theory."

He was very prepared in "a lazy way" to let others do the speaking for him. There were always ‘leaders’ who were better at it than him and more prepared to speak up. But also he believed those leaders were prepared to be pushy and bully people into being involved in things that they weren't really interested in. He saw them as ‘theoreticians’ who hid behind a facade of ‘knowingness’ but were just as insecure as everyone else. Yet he still believed that everybody’s contribution to the place was vital though they operated in very different ways. But with Gary de Vere and Colm Clifford somehow he was made to feel that he was not ‘measuring up’ all the time. This at a time when he was experiencing difficulties in coming out at school as a teacher.

Peter's views on the shift from squatted households to redevelopment into single person flats as members of the gay section of the Brixton Housing Co-operative:

"I don’t particularly like that idea. If you have got a community and it is still being thought of as a community because there is that communal garden and you can’t ignore the history of the place....l would have thought that to build any kind of flexibility into it as a project there should he at least one house....making it all into self-contained units to me seems to be a little bizarre. Really inflexible because it doesn’t allow for any kind of change. At the moment I live in my own unit here and I share a toilet and a stairway but it’s not a situation I see myself living in forever. If I did have some kind of control over the design and architecture of a whole area I would try and build in some kind of flexibility like that. It seems to me that living by yourself is part of the regression of living in the 80s as much as anything. I didn’t think the whole thing was going to be turned in to individual flats. I thought there were houses that were going to be left as houses (i.e. communal)."

"But you see, I think....what happened in Brixton during those days wasn’t something that was planned. It was, as Truffaut would say, an 'event sociological'. We used the kind of structures and buildings that were there....and they were structured for family units....we totally changed them simply by....I mean, there was two households that wanted to be large, which was 157/I59 (Railton Road), and we just knocked a hole through the wall. We had a kitchen in one house and a bathroom in the other and it became this great big living space. I don’t see any reason why, though I haven’t seen the plans for the places, why this couldn’t be done with the houses. I don’t think you can actually plan an event like Brixton so I don’t think you can actually plan an architecture for it. In many ways there were times when it was as communal as communal could be given the structure that we had. That has a lot to do with it. I mean, there were a lot of other things than the area of sexual politics that we challenged within Brixton. That was around privatisation of space and property and things."

The problem around communal living and its encroachments on individuality:

"One of the big dangers within big communal structures or co-ops is that you lose yourself to this wider theme. I always think that it is important that you keep some sense of privateness, of your individuality, which people did in their rooms. If you looked at peoples’ rooms in Brixton you could almost have an exhibition on the types of rooms people had. I mean there were some attempts way, way back in the beginning to even have communal bedrooms which I am very pleased to say were opposed. You wouldn’t have been able to have all that intrigue of popping in and out of each others beds if there were communal bedrooms."

Peter's views on 'class' the subject of which was never really approached in the community:

"I'll say a few words about class then. I feel something should be said about class in Brixton because to me one idea that was spoken about at the time was that our sexuality cut across race and cut across class and that it was this great unifying theme that united....you know, that cut across nations because Brixton was composed of a lot of Australians and Irish and Continentals and English. There weren’t many blacks there... Bruno (de Florence). There was this idea that we cut across all these barriers and I don't actually think that was the case. What we tended to do was ignore a lot of those issues."

On Gay Men's Week retreat at Laurieston Hall (explain). Some felt it was a 'cop out' by replacing 'real' urban struggles against oppression with individual self-development in a remote country retreat:

"The split in the community between people who thought that all the struggles should be worked out in the city. You want my views on it. I think that was the time when the big splits started wasn’t it. I mean I think that was probably a real important event."

"I wasn’t very much aware of it at the time. I couldn’t work out why so very few came from Brixton (to Laurieston). It was only in a conversation with Ian Townson who said that the struggle was all in the city and it was ridiculous to go all the way up into this country retreat and eat oak leaves. I’d agree with him about the oak leaves."

"I think it’s just, you know, with any oppressed group you just get incredible amounts of internal splits and bickerings. I think it is a lot to do with the fact that you are an oppressed group to start with. It’s too simple to talk about one lot feeling like being into personal change was important and another lot thinking about wider things. It seemed as though that is what it was all about at one time. That us 'brown rice' lot were getting into co-counselling...it seems that it was all down to the contradictory basis on which Gay Liberation was established anyway which was the personal is political."

"For myself l really felt battered by the whole thing of coming out at work. I did find that really exhausting; all that upfront, out there, Left kind of politics approach. I wondered where it had actually gotten me. I knew it was very important in terms of...that there was now visibly a group of gay men around but I felt a little bit exhausted by it. It didn’t answer any of the questions....well, they still haven’t been answered."

"Of course we exaggerated. That was the whole way everyone approached politics there. Everybody exaggerated the stances that others had made. So while we were kind of narked about the brown rice label there is a sign on the walls in Brixton which I think sums up a lot of the way that the group responded: ‘They exaggerate their forms of outrage’. It’s written there. I really think that’s how the two sides kind of responded to each other. Because that approach was disapproved of slightly we became more and more split until basically the brown rice lot and the others had absolutely no communication between each other at all. Originally before the Centre broke up it was everybody against this group of people who identified as bisexual, the nerds. Then it just became more and more split."

On the question of women living in the houses:

"Yes. Jan and Rosemary lived there for quite some time (159 Railton Road). It made quite a difference. Some gay, some not. Then Sandra Cross lived there for a while (Peter Cross's Sister). The whole community seemed to be separatist in terms of heterosexual men. There was almost never any straight men coming to the house. Then only as highly vetted visitors and that applied throughout the whole community. Then women visited the place and stayed there. After Jan and rosemary there weren’t any gay women living there until Anna Duhig came back again. There was Maggie living across the road (146 Mayall?) at one time. There was unease about women living in the community for various reasons (unstated).

Peter retold the episode of the police raid for drugs at the houses and Peter Cross’s and Jamie’s arrest. The embarrassment of being discovered in bed by police or sitting around the garden in drag after an event at the Centre when they came swarming over. People had to decide in twenty minutes who would take blame for the dope plants avoiding confessions from those who already had a criminal record and anyone from another country to avoid the risk of deportation.

His final comments on time he spent in the gay community:

"I still have an incredible nostalgia about it somehow. As if it was a very important time for me. I almost felt I grew up there in a way. I kind of had my childhood all over again. That was one of the wonderful things about Brixton. l felt like I could play. I tend to be serious. I still get very nostalgic about it at times. But I see it as very much something that is in the past which was creative but can’t be recreated."

Micheal Kerrigan, Terry S, Jim Townson (Ian’s younger brother). Notice the tacky mock regency wallpaper

Stephen Gee, Micheal K

Front row: Terry S, Jerry Comey. Second row: Stephen G, Edwin Henshaw, John L, Ian Townson. Third row: unknown, Paul Newton, Malcolm Greatbanks. Fourth row: unknown.

Left to right: Derek Evans, Paul N, Terry Jerry C.

-

Stephen Gee had been involved with the gay centre and Brixton Faeries theatre group prior to his arrival in Brixton from his flat in Gipsy Hill during the ‘very hot summer’ of 1976. He moved into 94 Railton Road for a while but left after attacks from “those white National Front types…..anyway they were certainly anti-gay.” He moved across the road to where gay men had already squatted households and experienced contradictory feelings of being supported but at the same time there was also the expectation of having to prove your worthiness before being accepted by the ‘together ones’ especially at 159 Railton Road. A squat was opened up at 152 Mayall Road where he lived for a short time with Jim and Ian Townson and Terry Stewart. He felt a little more settled and got involved in activities now that they had become centred in the squats after the gay centre had closed.

During that summer, after a chaotic start and fraught personal relationships, he felt there was a growing convivial atmosphere with people being in and out of each others houses:

“There were arguments but they didn’t seem to be the kind of devastating things they became later……it was fluid among people. That must have been something to do with the similar age group of everybody in the houses at the time……I think it was a time when 159 and 157 (Railton Road) were one church when they cut a hole in the wall (to join them together as one communal household)……There were lots of things happening in the back gardens……I enjoyed the atmosphere……that seemed to continue for me all the way through. It was very lively. I know I felt very lively at the time.”

“……but there were already certain things starting to happen that I couldn’t have carried on with. Like being surrounded by people who were totally dependent. We were all dependent on each other for certain things but some people just proved to be a total dead weight……challenges to people became very sharp and very mannered and confrontational……too much care or too much confrontation. Not really anything which could transform both those things into something that could be used positively. The activists became separated from the caring ones at 159 (Railton Road)……it was a real division between people. But I suppose I allied myself with confrontation really.”

Stephen moved to 146 Mayall Road squat where a fraught personal relationship continued to cause tensions along with further difficulties he experienced especially lack of emotional support that he needed at the time. Despite this he developed a very strong friendship with Colm Clifford which led to a fruitful melding of creative talents in writing, song and drama. His views on love and sex:

“…..I never saw relationships in the houses in terms of free-floating sexuality…..my relationship with John Lloyd wasn’t like that. It wasn’t shared with anyone else and if it was it was extremely fraught…..I think we were absolutely monogamous and I think that was the dynamic of it……there is often a picture of the gay community, how some people picture us, of people having continuous orgies. People couldn’t cope with that. I don’t think so, really. They perhaps could in some of the houses. Perhaps they did in 159 but I think that must have been problematic. It certainly didn’t happen in the houses that I lived in. Most people were single but others paired off. There was me and John Lloyd at the time. In 159 there was David (Simpson) and Robbie (Campagna), Maybe Jamie(Hall) and Petal (Peter Cross). There was Terry (Stewart) and Jeff (Jeffrey Saynor) at 157 Railton Road.”

What Stephen missed out on most was his failure at the time to pay close attention to building better personal relationships with people he was living with in the houses and to invest more in the upkeep of the buildings:

“Partly I was always out doing things. I was always acting (theatre) and looking back I would have have wanted to be more constructive in terms of relationships in the house at the time……with people I felt closer to as friends. But those questions were continually overwhelmed by things that were going on like the theatre group and acting in gay festivals…..There was also the difficulties of doing the house up and all that kind of thing. I never really got to grips with it. So there are things that I neglected.”

His thoughts on gay-identified politics:

"Well, the idea that there is some unity which will come out of all gay people, which will transform them and the rest....you've just got to build it and let it work away and we'll all come together. You know, gay centres everywhere and people on the streets....it will build towards some kind of confrontation....which was the sort of picture I had and I don't believe in that anymore. I don't think it's true. I actually don't think it was ever really true but it was how we felt. I don't think it was really about what was possible. Even In better times (than now) I think we misconceived certain of the questions. They were misconceived because I suppose we were very full of ourselves which had its good sides and its bad sides and I think there was a kind of chauvinism about it in a very negative way which didn't relate enough to other questions. It didn't take into account the difficulties of people living outside of the sort of sheltered environment of Railton Road. Railton Road isn't sheltered in lots of ways. There's bloody holes in the roof (laughter). In other ways, to me, it was a very internalised thing. At its heaviest it's just really deadly because people just don't move outside of their own backyard at all and it's a dulling kind of thing."

On being asked if the splits were mainly political or because of personality differences:

"It's difficult to say. I think to sort of make them very grand and say they were all about huge principles would be making it very grand really. It's because people couldn't really talk very directly to each other on a personal level that they happened and....l suppose there are lots of reasons for that really. You can't really pin any single one down. I don't think there was any great kind of political, decisive significant battle being fought out between certain houses on Railton Rd of heterosexuality versus homosexuality or tensely internalised personal politics versus street politics. There were those influences at work but they weren't decisive in Railton/Mayall Road. People may have thought they were at certain times. l don't know."

Stephen was very clear about the earlier days of gay liberation with high hopes and euphoric expectations now crumbling as people went off in different directions:

"That was influenced by the political climate of the time that they were able to sustain (euphoria) in the first place. Certainly it is connected with that but I think among the high hopes there were high claims as well. High handedness at times. People couldn't live up to it really. Not enough criticisms of how we thought about things I suppose. People would be critical with each other at times in a very confronting, heavy way which enabled people to avoid other issues then because they'd have a few scars. The contradiction between the givers and takers.The poor state of the houses and outside aggro were contributory factors to community tensions but they were not decisive. No, l think it's more complicated than that. I don't think it's a question of ‘if only we had decent housing we'd have had decent relationships’....l don't think it's necessarily as simple as that."

On the redevelopment of the gay squats into Brixton Housing Co-operative flats:

"Now that the houses are going to be done up it's interesting that people are choosing to live as individuals, totally. It's going to be, as far as I can make out, single person units. lt then no longer exists, the idea of living together. l don't think it will be the total end. You don't know what that might bring about....

There will still be the communal garden:

"Yes, but it's not the same. That's not to say that it should stay as it is....that people should be forced to live together or anything like that. But there's a whole mixture between choice and circumstance and putting up with things and, you know, enjoying things. I don't think people have really ever had an idealised community. It was always referred to as the community. it was more flexible so that there could be more variation in the way people lived. There could be privacy and things. A commune is supposed to be free-flowing. That is....if you are forced to be free-flowing at times that can be quite rigid. There's flexibility and there's room....space....for people. l suppose that is partly why it lasted "

What did the Brixton gay community mean to you in terms of self-confidence and coming out:

"Well for me it did give me a lot more confidence. It's certainly given me that. You didn't say you were gay because you were frightened of those kinds of things. Coming out in Brixton was a great help with that. You did get people all around you, you know. You got that support and people did talk about their lives. There was an openness in that sense and.... boisterous and party-like most of the time and that's what l needed for a few years."

Stephen moved out of the houses for a fresh start after four years partly because of increasing irreconcilable political differences between people but also though lack of personal growth:

"Well, I ran out, didn't I (laughter). It's partly a problem I'm still trying to work through in personal terms....having sufficient control in my own life. Partly it was, you know, l was leaving anyway. What happened to me was my exhaustion with the place anyway and wanting to move.l'd been there for four and a half years....my own lack of grip I suppose on personal things. Patterns which had run on and are still with me in some ways....just left me with a horror of the place really which has taken me quite a time to recover from. So I literally moved out just....hating it really. It doesn't, you know, jaundice all of my experience there. That was the end of 1980 when I left.”

-

John Stanbridge was introduced to the Brixton gay squats by Julian Hows who he met at a restaurant in Lordship Lane, Dulwich were they both worked. He was invited to share a house with him and Frank Egan (149 Railton Road) on a ‘trial basis’ for three months in about 1978/79.

He fully intended just to move in with Julian and was repulsed by the idea of living in a commune:

“……the idea of living with a group of gay men horrified me and I might add that experience has taught me that my initial fears were well justified (laughter)……It was very obvious that every body here led a very different gay life from the one I had led. I didn’t like the idea of living in a community of gay men……I think, I suppose, it smacks of the ghetto to me. Certainly from my past experience of being in Earl’s Court and before that in Chelsea at the end of the 60s. Ideas about gay men living together in huge groups were very much based on that. I suppose I was frightened of that as well because it was something I hadn’t enjoyed before.”

He stated that Julian had taught him to think about sexual politics but prior to that he had moved in very right-wing “nonthinking” circles from which he had gladly escaped. He saw himself as neither right-wing nor left-wing but as a “wishy-washy liberal”. He was affected in two main ways on moving into the gay squats. Firstly, he had never lived with a group of very politically active gay people before that also had totally different gay experiences to his own. Secondly, it was the first time he had ever lived in a working class area and had any contact with working class people apart from “odd sexual encounters.” He experienced that contact as an “enormous shock.”

John moved in “comfortable upper middle class or middle class” circles where attitudes towards someone’s sexuality were kept under wraps and the gay people he knew were very closeted.

This gave him a false sense of acceptance:

“I had led a charmed life. Nobody ever threw anything in my way. The one thing about working with fairly liberal people, I suppose one of the ethics of liberalism, is that whatever you think about what anybody does you never tell them to their face. You always say it behind their back. Consequently, being a fairly innocent, naive person (laughter) it never occurred to me that people might not like me for being gay……the first really anti-gay thing that ever happened to me was about six months before I moved in here. I was coming up to see Julian one night and I was queer-bashed on Coldharbour Lane (Brixton). That was the first time it had ever occurred to me that queer-bashing was something that happened rather than something you read about in Gay News or newspapers and things like that.”

In answer to a question about confrontation and tensions within the gay community:

“Well, that subsequently developed. Not when I first moved in. I was very quiet and kept myself to myself.”

But after his three months ‘trial’ period at 149 Railton Road he had to make a decision about leaving or staying. Unable to live with the ‘horrendous atmosphere of Julian’s nightmarish life (laugher)”, he decided to move into 152 Mayall Road where he got to know Don Milligan and Matthew Jones who also lived there.

Things started to take off from that point:

“It was really interesting……because I’d also got to know Anna (Duhig) and Veronica (a visitor from abroad) who was living with Anna. Anna was living in 157 (Railton Road) with Malcolm (Watson). The power struggle in 157 was enormous. Absolutely dreadful. Then it would be resolved by one of them moving to anothyer Monarchy. Another empire somewhere else (laughter). Anyway, Anna and Veronica decided that 159 (Railton Road) was going to be a Women’s house….So I got to know Anna quite well and was well versed in feminism.”

His stay in the squats opened up awareness of himself for the first time as a person with strong views on many issues. After overheated arguments about political differences with Don he was even more entrenched in his view that he distrusted organised politics whether on the left or the right.

He was scathing about people’s motivation for engaging in revolutionary politics and the ‘cult’ of leadership:

“It suddenly started to occur to me……that the only reason people are very keen on political theories and poltiical philosophies is because they always imagine that they are always going to be leading when the revolution happens (laughter). I think I always suspected this for a number of years……I have no desire to lead anybody else and I have no desire to be led.”

“I think coming here hardened me very much in terms of working out what I thought and what sort of world I wanted to live in. I do not have a very well thought out view on Patriarchy but do have an innate distaste of it……I have met a number of people……who spent most of their political life decrying Patriarchy. I think I have managed to fall out with most of them at various times because the people who cry about it most I think tend to be people (men?) who are preserving their own patriarchal status within the gay community. I feel very uncomfortable saying this even though it’s true.”

He viewed the unstructured nature of the gay community and it openness to those who wished to live there as having the greatest positive value born out by the fact that other, more organised gay communities had ‘been and gone’ and that the Brixton gay community had lasted for almost ten years:

“But one of the things that has allowed this place to survive for so long is the fact that there are no rules, no regulations, no leaders. Some people come here as a last resort……so what……you come here and if you are broke and unemployed……there are people here who will talk with you. They are not particularly going to interfere with you or shout at you and tell you what to do……At least you have a resting place to work it all out……despite what actually appears on the surface (people) really do care about each other in this community.”

John caused controversy and hostility in the community by having a heterosexual relationship with Anna which was seen as a direct threat to gay liberation politics and values and an inexcusable intrusion into the community. For him this highlighted a double-edged form of hypocrisy from those who professed feminist politics and non-monogamous relationships. A number of gay men had paired up into couples in the community. He finally concluded that all the political arguments had been handled badly by everyone concerned in an unforgiving acrimonious atmosphere.

During the transition to Brixton Housing Co-op single person flats he was asked how this affected relationships between people in the community:

“Well, I think it had to be because that is the outside world dictating conditions upon us. Even though Brixton Housing Coop was started by people in this community (gay involvement in it!) it has a very formal structure and it has rules and disciplines. How it came into being was through people needing to get away from the squalor of this community. But the two things go hand in hand you see. Squalor brings you all sorts of freedoms that you will not get with central organisation? In that context, yes people here, especially people who have lived here for a long time like Malcolm (Watson), Henry (Pim) and Andreas (Demetriou), you know, everybody reaches a point in their lives where they do want some sort of material security like a not leaking roof and fixtures and fittings I suppose. But with that you lose it. Now the community, well yes, we're more than neighbours but much less than a very carefully thought out co~op. Living in this squalid, decaying environment, which as I have said gives you all kinds of freedoms, gives you time to think. You don't have to do anything except make sure that you don't wake up in 6 inches of water.

I think a lot of people still think it is going to go on the same way when everybody is in single person units. It isn't. It's never going to be that way again. If we all woke up tomorrow morning in single person units it might have been possible but there is going to be such a huge gap and people who are involved in it now who are very keen on the idea might now move in in two years time. They might have found somewhere else, moved on somewhere else. I just cannot conceive of it going on at all in the same way. Even though I will fight against it myself very, very much, I think gradually the whole thing will become absorbed into Brixton Housing Co-op. The whole thing will lose its sense of identity completely within the next 3 or 4 years. But that is because, I mean, they are squats and they're decaying. The world outside is decaying as well. Everything that we thought about, everything that everybody fought for, except me, in the 70s....well, it just ain‘t going to happen. That's decaying as well. So, perhaps as everybody goes back to entrenched middle class families, and I think they are doing that, perhaps it's as good a time as any to wind it all up. No doubt somewhere else something will spring up and do exactly the same thing. I suppose one likes to think that one has been part of something unique in history but what we're in really is....

But the houses are falling down so we have been faced with decisions about whether to live cooperatively as we've been going along or to go into single person units. Well, there is no way when you are paying rent, when you are going to have to start paying electricity bills, gas bills, rates bills regularly, there is no way the community could have gone on within that formal structure in the way that it has done over the last 10 years. So that is why I think people elected to go to single person units. I don't think people are very aware of what they are actually saying. It is the end of it.

With the changes in the area that are now going to occur....The reason the community Is here is because it is in a very socially volatile area and that area is no longer socially volatile. You see, I think what was really the death knell for the gay community and it was probably the death knell for Brixton as well was the riots. Seeing how people reacted to the whole thing in relation to the riots and the government and the way that politics are going....You see the thing that the riots taught everybody around here, if it taught them anything at all, was that revolutions actually change nothing. They just change leaders really or reinforce the ones that are in which is what happened in that case and a very good cosmetic job has been done on Brixton. it has been torn apart. It has been absolutely torn down. There will be no blue plaque to the riot ever. They'll be forgotten. The place will be tidied up and will become a very middle class area. When these houses are done up it will be a gay community but it will be, in a few years time it will be a very middle class community. Very meaningless as a community. Whether I am here or whether l am not I will feel very strongly as though I am living in a block of mansion flats in Earl's Court. It will have the same significance. It seems very pessimistic but I don't thing the same value could possibly come out of it. It has already come out of it because the reason why there was value here in the first place was because for a lot of people this was the last resort. However negative anybody else might think that is, if It's the last resort in housing, which It is really, I mean you couldn't get much worse unless you actually did build a mud hut in the garden....in this country....when it's the last resort, I think. and when you actually get that close to being against a wall, socially and economically and politically, that's when you start to think about yourself. l think that is the one thing this community has done. it allows people to think. Even if it has made them think negatively. Some people thought about and opted for middle class values. I strongly suspect I will do the same as l get older. I shall keep my central heating on for most of the time (laughter). But that (community) I cant ever see happening again here. It will happen somewhere else. This area will go up, another area will go down and the same thing will happen all over again. If we aren't all nuked.

But you see it is only in situations like this....it is only when you have lost everything that you can actually start to define yourself in any way at all or be aware of yourself as a person. I don‘t think you.... you see the answer to that would be that it is a very bourgeois attitude to take because not very many people have the time to sit around thinking about themselves. They're too busy finding jobs, doing work and this, that and the other. What is the point of coming into a community like this unless you suddenly realise, yes but why do those people spend all their lives looking for work and doing this, that and the other. It's actually a bloody waste of time (laughter). They'd be far better off with nothing and thinking about the sort of world they wanted to live in rather than them voting Conservative or Labour and be told that if they work they will be given a nice place to live.

I am certainly a very different person than when I first moved in. Once you have made that step I think there is no going back. It's a ? experience and you can't really wipe it out, I mean I still have contact with people I knew 10 or 15 years ago and there is now just this huge, huge gap between us. If you set out looking for security then you will never change. I find it horrifying that people I knew 10 or 15 years ago haven't changed at all, They haven't thought about anything. They have just got more and more entrenched in their own personaI....it‘s not the security of their jobs, it's the security of their unexplored egos. Does that make sense? Because they have never looked at themselves then there is nothing to be frightened of. They've never had to question anything. For a lot of people I know, being gay has been....the end of the 60s and glossy, semi-closeted clubs. Pretty clothes, dolly boys. When I look back at that to quote Hartley?, I mean that really is a foreign country,. The Past really is a foreign country. When I look back at that person as me then, its like looking at a stranger. Those people who l knew then, they still are dolly boys, ageing dolly boys. It's very sad and very pathetic and their lives have just been dominated by sex rather than sexuality.

Yes, individuality. It's the only way I can think of contributing anything to society anyway. My one fear is that they (Ieft and right-wing leaderships?) are no longer prepared to let individuals contribute anything. With thousands of years of history of people being sheep, it's about time they stopped being sheep and shepherds. More shepherds should come into the shelter’? of the cottage (laughter).

-

Malcolm Watson studied psychology at Warwick University for three years and occasionally visited Brixton. He was invited by Alastair Kerr to live in the squats and moved there in 1978:

“I did up a damp basement in one of the houses. The room next to it was half full of trees and rubbish and plaster and cement and garden earth. That was the basement of I55 (Railton Road). I lived there for about a year before I moved up onto the ground floor of 157. It was so damp the 155 basement. It was dreadful. It had wet rot on the floors. I had to dig up the floorboards to get rid of the wet rot floorboards and fill it up with cement. Cover it over. I had to replace a broken window and put the electricity in and the gas fires. I had to do a hell of a lot of work and I managed to do it on my £50 (remains of a student grant) and then basically I was unemployable in that period…..Well I was in two. 155 and 157 for about 7 years. I think it was 6 years in I57. That would bring me up to I985. Then I move here in 1985 or 86 (Milton Road ). That means I have been here about 11 years. It was during that period when the squats were being taken over by Brixton Housing Coop. The Brixton Gay Community Housing Coop merged into BHC.”

He was asked about the reasons why people squatted in the gay community:

“Well, people brought themselves there for different reasons. Often is was homelessness. It was to do with housing shortages. But also the idea of living together with lots of other gay people appealed to others. Some people made a community within a house and others moved around and related to two or three houses. Everybody had different patterns of interaction.

159 was kind of separate from the rest of the community. They had their own little house community. It was an experiment in communes in a sense. I saw it as that....Expectations is an interesting point because everybody came with their own expectations. They all had different expectations of what a gay community was or should be. I hope that it would be a place where people could freely interact and come out of their back doors. That it would all be one house. A much larger house. But there were some houses I didn’t want to go into myself and didn’t. There were others I went to repeatedly. I spent a lot to times in those days in 152 and 146 (both Mayall Rd). I was rarely in 159. Very rarely. I was there once for a Christmas do we had. My god, I remember that. We all put £2 in....

We all put £2 in for a Christmas do at 159. Aunty Alice (Alastair Kerr) had organised it. Jamie Hall was absolutely, totally 100 per cent against it. It was like saying we were celebrating Christmas instead of saying we were celebrating Yuletide away from nuclear families. We had a really slap up meal. For £2 a head it was an enormous amount of food. We stuffed ourselves and gorged ourselves and Jamie Hall went to Barnardos as he did each Christmas time to feed the homeless and the down and outs. The first day we had a fabulous meal. On the second day there was so much food left over that we were able to repeat it. Jamie came in that day and joined in. But he gave us all such a fucking guilt trip. I had the worst headache I had ever had in my whole life. Too much wine as well. I had the most splitting headache. The tensions between someone saying it was much better to go and feed the down and outs than to greedily indulge in a yuletide, winter, stuffing-your-stomachs festival. To stretch your stomachs for the next three months of horrible winter.

It did fullfill some sort of function. Stuffing yourself at that time of year because the next three months are going to be cold. So you need to eat more in the winter. So I could see a very good reason for doing it and as far as I was concerned I was not repeating the Christmas meal. It was completely different being surrounded by other gay people. I can‘t remember all the people who were there. There was about ten of us.

Yes. I remember Alastair and Jamie Hall because the tension was between them. It was a big issue you know. To think about it now. At £2 a head it was fuck all. It might be £10 now or even £20 we spent in todays’ monetary value. That must have been around I980 or something. Round about then.”

He recalls the communal meal at 148 Mayall Road, Henry and Andreas’ squat, and the strange effect of the brood of hens on his imagination:

“It might have been Henry or Andreas’ birthday. Summer or Autumn time. I979 or ’80. It could have been early on. In fact I was going to move in to 148 Mayall when I came down from Coventry but Henry and Andreas moved in before me....I actually did stay in Alastair’s room one summer (146 Mayall) when he went off to Canada. I also stayed above the Gay Community Centre when Alastair went away for three months. He was living above the Gay Centre as caretaker and I did it for three months. I looked after floats for tea and biscuits and things like that. It was absolutely incredible that period. I couldn’t have done it for longer than three months. But it was amazing. I mean Alastair did it for about three years. I also stayed in his room when he moved to I46. Between ‘75 and ‘78 after the Centre was closed and it was adjacent to Henry and Andreas’ chicken coup on the other side on Railton Road because at that point they weren‘t in 148 they were in 151 or I53 Railton Road.

I remember waking up one morning when the sun was shining through thin curtains, round about sunrise, hearing this reed music in my head; flutes, clarinets, oboes and cor anglais playing. I came really slowly to consciousness and this reed music panned into a whole gaggle of clucking hens. What I‘d heard in my dreams were the hens but it had sounded like this beautiful reed music. The woodwind section of an orchestra playing music. I came too and realised it was the hens clucking. I will never forget that. It was a wonderful experience having the hens clucking becoming this beautiful music....that (for me) before I actually moved in was what made those back gardens, what we called Brixton Fairyland, a unique place. Quite a wonderful place in the middle of a city. I suppose an experience like that, which wasn’t a human interaction experience, was like a good ‘vibe’ from the place as well as the people. 146 back window was certainly used as a back door. It was level with outside garden.”

click on the arrows to scroll through the images below

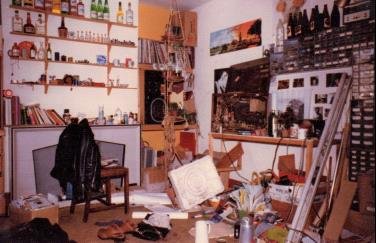

photos of 148 Mayall Road, where Andreas Demetriou and Henry Pim squatted

-

Derek Cohen on several occasions met people from the gay squats at the Oval House Community Theatre where a gay group met informally each Sunday. He was looking for a place to live after experiencing homophobia from the people he was then living with:

“In 1978 I started sharing a flat in Hampstead Heath with a straight guy. Patrick and I got on fine for a year or so. I had my own bedroom where I often had sex, either with friends or the occasional “straight” man from the pub I frequented at the bottom of the street.

But one day Patrick told me “You know I can’t take all this sex you’re having seriously.” I was shocked and upset at the homophobia that emerged.

The next Sunday I discussed it with my friends at the Oval House and they said I needed to move. There was an empty house suitable for squatting down on Railton Road in Brixton. It wasn’t joined to the rest of the gay community, but there was only one house in between.

So, like alternative estate agents, they met me down there to look over 145 Railton Road. They all had experience of squatting and doing up abandoned houses and could help me assess whether it was habitable.

The roof and floorboards were sound, but many of the windows were missing and there was no electricity or gas around the house, though there were meters in the cellar.

Finding windows was easy. There was some rehab going on in the neighbouring streets and the skips contained suitable windows. The windows and frames for the houses seemed to have been mass produced. When you put in a window frame from the skip the screw and nail holes in the frames lined up perfectly with the holes in the walls.

If the glass was broken I already knew how to glaze windows from my residential social work days where residents were often having tantrums and throwing things through the windows.

Sorting out the electricity and gas was a bit harder as I had no plumbing skills, and my electrical skills in the past had regularly resulted in nasty shocks. But friends and squatter neighbours were on hand always willing to help.

One showed me how to solder copper tubing into the lead inbound gas pipe and how to plumb the gas into the kitchen, and I think, a gas fire. The plumbing skills were handy for piping water to a salvaged kitchen sink (which doubled as a washbasin) and the toilet. There was no bath and so I used the bath in other people’s houses.

Another helped me install an electrical ring main around the house so we had lighting and power sockets. Skips were always full of useful stuff, and sheets of wood and wall studs were soon fashioned into a kitchen worktop. I’m afraid my experiences fitting a house out from skips has left me with a life-long obsession for never throwing away today something that might be useful in the future.

Some of the doors were missing, noticeably on the (only) ground floor toilet and, being radical people, none was fitted.

I shared the house initially with a Dutch work colleague – Hans (Klabbers) – who I was having sex with and who wanted to move from his parents’ home.

Soon after two other men joined us.

Colm (Clifford), a veteran Brixton squatter, moved in after one of the frequent bust-ups that occurred in the various gay squats, and an Australian, Paul (Coyle), joined us around the same time.

Colm and I did work on Homosexual Posters together and there were sometimes planning meetings at 145 if not Union Place where Colm worked.

Colm and I had sex on occasions while we lived together. He was from Ireland and was very sensitive to the British oppression of the Irish. However my Jewish background meant that I was the only Brit who he would let fuck him, he claimed.

It was a time when you had sex with someone because it was fun and you felt like it; not because it meant anything significant.

The Hans crisis

My friend Cordelia went to live in Japan for two years and in 1979 I went to stay in Tokyo and Kyoto for four weeks to see her and explore the country.

On my return it wasn’t quite folded arms and rolling pins on the doorstep but not far off.

Colm and Paul were outraged.

Colm had been hunting around the house looking for some fresh porn and had found some straight porn under Hans’ bed.

This was a gay squat and a straight man didn’t have a place there.

Hans wasn’t apologetic and said he’d always had an interest in women as well as men. This was a time when “bisexual” was usually equated with “closeted”.

Hans had to move out and, after much discussion and heart searching, I decided to move out as well and we found another abandoned house on Mayall Road which we occupied.

This one was in much better condition and had running water, gas and electricity.

My mother in Manchester bemoaned the move, saying I should find somewhere proper to live.

I replied that I was on the way up, as this one had a bath.”

-

Don Milligan arrived at the gay squats in the summer of 1980 at a time when the original spirited elan of the community was winding down during the transition to Brixton Housing Co-op single person units. His stay in Amsterdam had proved to be difficult for economic reasons but on his return he did not wish to live with his family:

“……so I ended up being interviewed by Colm Clifford and his household as to whether they would permit me to live in their squat in the gay community. So, the upshot was that a place was found for me in one of the other houses……I lived in two houses there. One in Mayall Road (152)……and I lived at the one in Railton Road. I can’t remember which one I lived in first.

I hated living there. I hated squatting and I hated living there because I was running round the town at that time. l was clearing the tables in the cafeteria at Debenhams and washing up and doing this kind of thing to survive for a lot of the time. Or working overseas Containers Ltd. as a temp clerk. Or going on a typing course at Pitmans. What have you. I was doing all these things and it was very insecure. When have l not been. But this was a particularly sharp period. I felt as if l was shipwrecked. l felt as though l was clutching to a bloody raft frankly. I was very, very insecure and l did not like the gay community in the squat at all. Most of the people all felt were extraordinary in the degree to which they had a conception about how people should be gay and what they should be like. If you didn't fit their conception of that then they were exceedingly intolerant. The interesting thing was l have always been politically intolerant and was at the time and they were socially intolerant. So, you get those two intolerances come together and people would pass each other. I was intolerant about one set of things and they were intolerant about another set of things (laughter). People passed each other.

l wouldn't say that l connected or gelled or whatever was going on. What has become subsequently clear to me is that most of those people were very bourgeois. Almost exclusively, l would say, solidly middle class if not upper middle class people. That led to a certain kind of blaseness towards material questions and a refusal to say, you know, what. . . .Colm Clifford and other people saying ‘What are you worried about.Why are you getting so tense about clearing tables in Oxford Street.' You know, so their small time literary activities or their small time pottery or their small time this, that and the other created an atmosphere, a certain kind of Bohemian ease, an affected ennui about the place that I simply couldn't participate in. Not out of any disapproval though l did disapprove obviously. l just wasn't able to participate in the easy ennui of it. l felt that their attitude concealed considerable political reaction which l think was subsequently shown at the time of the Brixton riots. There really were very sharp tensions that appeared. So much so that when Tim Lunn was arrested and jailed. l was accused of being responsible for this in some way. I remember....because of participating in the riot and therefore leading this young man astray. In some sense this seemed to be Barry Prothero’s et als position.

The fact that Tim Lunn was found in the house when the police raided it with photographs of himself posing by his burnt out car and so on....and he made a confession in Kennington Road police station and didn't seem to know how to present his case in the most positive light to the police, despite his expensive education, none of this was taken on board. The general view was that it was a product of irresponsibility and a kind of chaotic attitude to the event by a number of people notably me. That was the hostility at the time as l remember it.

But you see Andreas‘ problem about communal living and so on was defeated for a number of reasons but I would think very largely in the first instance it would be defeated by architecture. There was a serious architectural problem. These were small, working class artisanal houses, most of them. Built rather cheaply, thrown up rather cheaply in the late 19th century. In fact there were no large spaces in them in which communal eating could take place, in which communal washing could take place. Unless extensive alterations had been made to the houses to permit the construction of Iarge dining rooms or a large laundry or whatever, then it would have been an extremely difficult thing to achieve. I mean I think communal eating and communal washing and those kinds of things would have broken down eventually through all kinds of social and cultural pressures. But they would have got started if the architecture had been different.

I think what they wanted was, not to put too fine a point on it, what they wanted was sheltered accommodation (laughter). The old person has a room where they can move a few sticks of their furniture in. They have access then to a wider circle of people, to a warden, to perhaps a dining room, they have access to a wider number of facilities, a local doctor and so on. On the basis of their initiative. They can go out of their room and participate in wider associations with other old people or with the authorities or whatever and then retreat to their own space. Shut their door and then they have their privacy. I feel in a way the desire of most people in there was about sheltered accommodation for homosexuals. There was a dual idea. There was the idea of having a private space and then having a wider access to neighbours. To have a certain kind of neighbourliness. But then of course the neighbourllness was always restricted really. I remember considerable tensions between different households. I was never there during the period when everybody appeared to get on or there were open, neighbourly relations between everybody. There didn't seem to be to me. There was David Simpson's house down at one end which was very posh and snooty, even snootier than Colm Clifford's house.

-

Jim Ennis left Ireland at the age of nineteen, where he had been studying in Sligo, to take up a degree course at Ravensnbourne College of Art in Bromley, South London, in the late 1970s. He was living on Villa Road an almost wholly squatted street in Brixton with his lover and it was here that he met Terry Stewart from the gay community at a party. He called round one evening to 153 Railton Road where Terry was living and witnessed people being filmed there (Nighthawks?).

Squatting was his only option because he could not afford to pay rent and this first visit to Railton Road prompted him to move:

“When I moved down here I moved to 145 (Railton Road) which was empty. Obviously empty with windows missing and no water or electricity or anything. I spent a week there and to the water and electricity on and I realised the house next door 143 was empty. We went in there in the dead of night to check it out and I moved in there. On my own. Then Alan Reid and Jamie Dunbar came along and lived there with me. Also a guy called Michael who didn't stay very long. I eventually moved to 153 (Railton) when Terry and Jeff (Saynor) moved there. I Spent about a year in 143 with Jamie and Chris Ransome, Jamie's partner. That was about 1978 or 1979 after the gay centre had closed. I didn't know anything about that.”

When he first arrived in London he explored the gay scene including the Catacombs, the Sombrero and Napoleons but he knew nothing about gay politics until he came to live in Railton Road:

“I thought it was good. I got involved a lot in the gay liberation movement with the theatre, Brixton Faeries and organising the discos at Lambeth Town Hall doing the leaflets and decorations and things like that. Working in the community, in the garden, going to gay meetings and there were demonstrations. This was something completely different. Something I had never imagined. I didn't know there were gay men in groups like this. I didn't know anything about squatting except what was on the news. That's why I went to Villa Road. It wasn't easy but it made sense to me at the time. I felt more a sense of freedom than I had in Ireland? Much more and much more a sense of community. I lived in very derelict houses in Villa Road. It didn't take long to fix up one room…..after I had moved into 153 (Railton Road) there seemed to be a lot of new people arriving and the community was growing. A lot of people just got into being crazy. We would dress up in drag and go around Brixton and go to parties. Sometimes we would be in drag for weeks on end.”

“We didn't feel like we were going out on the street in drag that we were confronting people. It was just something we felt like doing at the time. It wasn't conscious but it must have made a strong statement about our sexuality. We felt strongly about it and the more shit we got thrown at us for doing it the more we did it. We didn't really think much about those things before doing them. We just did them on impulse and that was the good thing about it. Doing those things together. I wouldn't have been able to do those things if I had been on my own living in a bedsit.”

“Wearing drag was one way that people could not possibly mistake us as being straight. This was to balance things out the other way because straight men were so straight. We used to go to opposite extremes. To preserve our own identity. It was supportive (against crap) not protective. Mutual support. That made it easier. There were times when I felt it was something difficult to do but we did not feel we had to do it. We just felt like doing it. Without really bothering why we are doing it or having any political arguments or reasons why. We just felt like doing it. Enjoy doing it. It became analysed and seen as 'right on'.”

“Relationship with the community? I feel at home here. It was easy living here and the time passed quickly. There was always people to be with and things to do. I don't know any better way I could have got through those years. The pace goes through phases at times according to who is living here a the time. Because when it began when I first got here there was only one or two houses and it quietly grew. But after I moved in there was a big expansion with several more houses acquired and a lot more people came. That was another phase then when people moved out to council flats it began to change again. It think the changes were a good thing. People moved out for change because these places were never seen as permanent. All the time when I moved in it was understood we would have to move within the next year or so. It never felt like it was going to be a permanent home.”

His comments on the transition from squats to Brixton Housing Co-op single person units:

“I don't know how that will work. They have to have communal areas because every house had a kitchen/living room...in every house there were one or two rooms where anyone in the community could just wander in and make yourself a cup of tea. Talk to whoever was there. The back door was always open. I don't think there was a locked door in the community ever. Except the front doors. It might still be possible to be with people. To go next door or whatever where people are gathered.”

“How was it possible for the gay community to exist? There were these people moving in at random because they needed somewhere to live. It was very random with no rules or regulations about who could live here and who couldn't. You could just move in without consulting a committee meeting or anything like that. We have people coming and staying just for a time from other places and countries.”

Alastair Kerr to the right of the ‘Homosexuals claim…..’ placard. On the far right at the end of the row is Simon Watney. The others are unknown. Brighton sea front with Sussex Gay Liberation front (1972 or 1973)

-

When Alastair moved to London he found it difficult at first to find accommodation:

“Pure fluke that it was Brixton. I hitched hiked up to London not knowing how to get a place locally.”

He tried the Gay Liberation Front office and the magazine Time Out with little success but he was given a telephone number of a flat where someone was about to vacate and was accepted for a room in a shared house with ‘straights’. The flat was located on Brixton Hill by Brixton Water Lane which was near to Railton Road where the South London Gay Community Centre would eventually be squatted.

Alastair moved to ‘Brixton Fairyland’ partly because he wanted to get more involved in ‘gay things’ but also to get away from his lover at the time. He had experienced hostilities from the straight people he lived with who took exception to his flamboyant lifestyle. But having experienced the threat of violence in the past and being aware of Brixton’s reputation for violence he felt he had to dress down:

“Living in Brixton there was a lot of violence happening on the streets. Particularly early on. I just felt much more relaxed not doing that. You know, not wearing eye makeup, not wearing multi coloured clothes, and I just thought I have had enough. It had just become wildly destructive and you lived expecting violence and thinking there is always violence there.” This at one point included a bottle thrown through the window of the squatted flat above the gay centre where he was living at the time.

When he first came to London he joined a gay ‘awareness’ group, possibly Icebreakers, that met in various people’s homes and through meeting Malcolm Greatbanks became involved in the gay education group. It was at this point that he got to hear of “a group of gay people in South London” (SLGLF) who discussed setting up a gay centre. He eventually occupied a flat above the gay centre that had also been squatted and became the temporary custodian of the place before moving to a squat at 146 Mayall Road early in 1976.

“I lived in 146 Mayall Road for 4 years. Anna Duhig was there first. John Lloyd moved in there not that long before I did and when I moved Anna was moving out anyway. The centre collapsed and in some ways it became a more enclosed group. But the gay community was growing and growing and drawing other people in and continued to do so all along.

As with the gay community centre, it wasn't long before we got threats from the local yobs and bottles through windows and things like that. One very ugly incident, which was very funny actually....this lot threatened us quite a lot. They lived just up the road, Mayall Road. They'd warned us, threatened us, shouted at us on the street. They really had intimidated people. Ian Townson had to flee a house they had broken into....flee stark naked. He had to flee stark naked. Very, very violent people. We watched for them. Hiding out waiting for them. They threw an old television set through a window (152 Mayall Road) and everyone came flying out and we chased them up the street. Various people like Terry Stewart and people in lovely pink, drag queens, ran up the street waving sticks at them. They fled in terror at this great big bearded drag queen. I don't know whether or not that totally intimidated them or what. But actually they didn't last very long because they were so abusive to other people. They insulted black people in the houses next to them.

So I mean we gradually squatted more and more houses, More and more people. Of course people have come and gone but it has always been a focal point for a lot of them. Contradictory things. A lot of solidarity and support but also a lot of bitching and back biting. Cliques. But I suppose that isn't different from any sort of people. There was the intensity of the fact that it was a gay liberation group that wanted to be special. Also the fact that the local streets were at times quite aggressive and frightening.