This chapter was written by Colin Lievens in collaboration with Joe Lawn

Joe and I had been collaborating for maybe about a year on and off before he started researching the South London Gay Community Centre and its surrounding history. At the time, as a non-binary person, he was having a hard time articulating why he was so drawn to this history, but it was undeniable that he really was drawn to it. He scoured the internet for old blog posts that mentioned it, he bought books that only had one page about it, and he hoarded grainy photos of the centre and its residents.

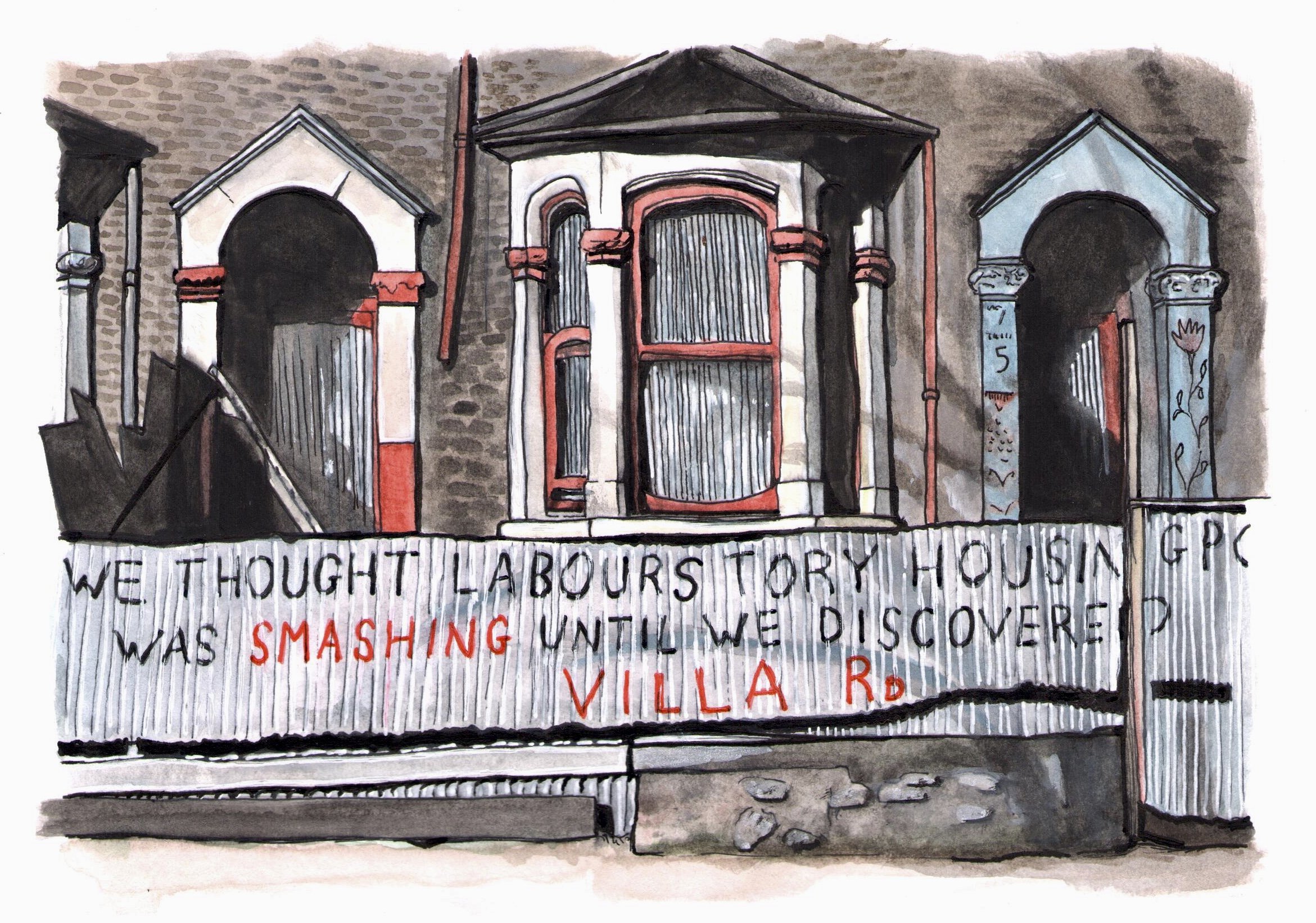

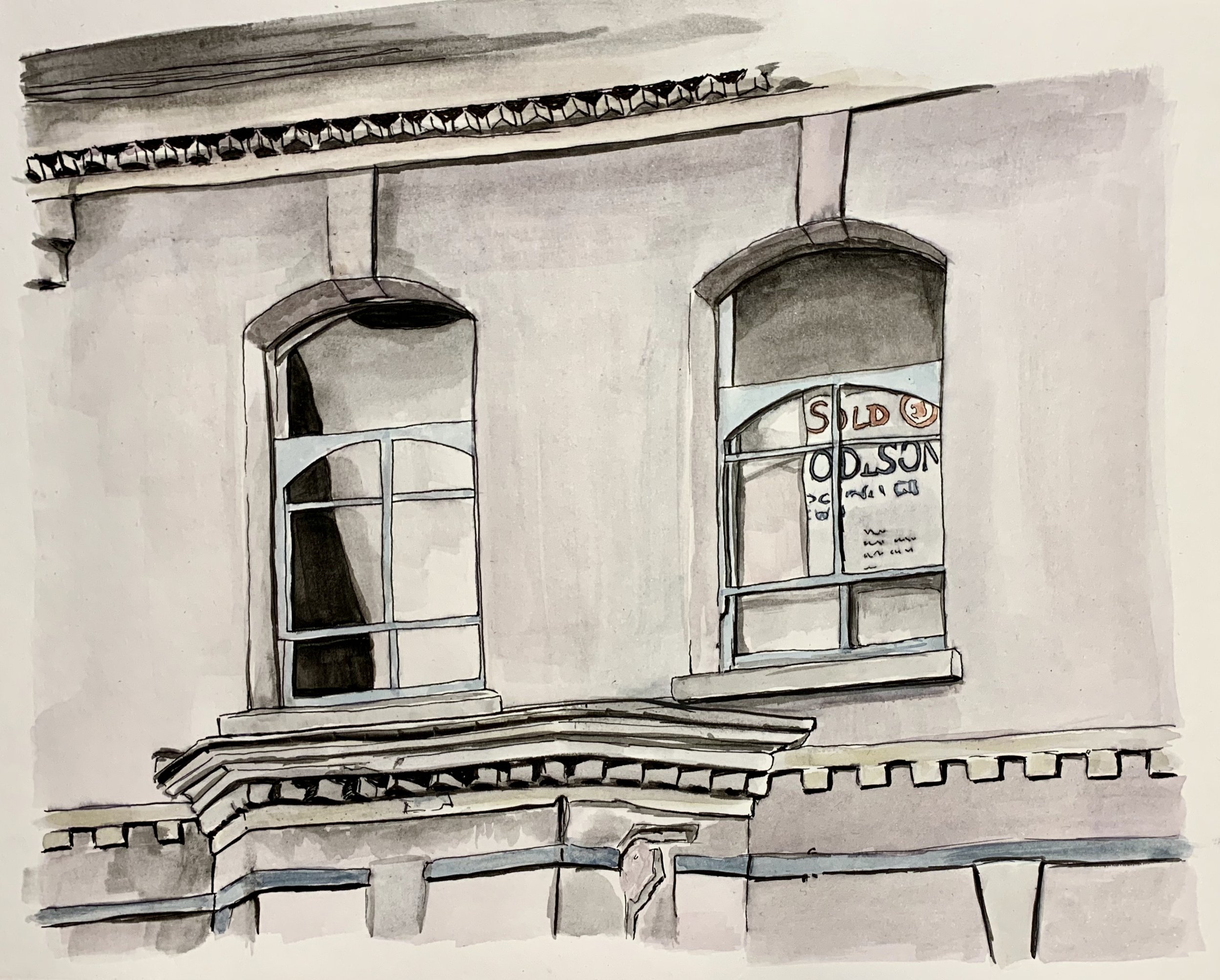

South London Gay Community Centre painted from a low quality image

Photo reference found on Past Tense blog

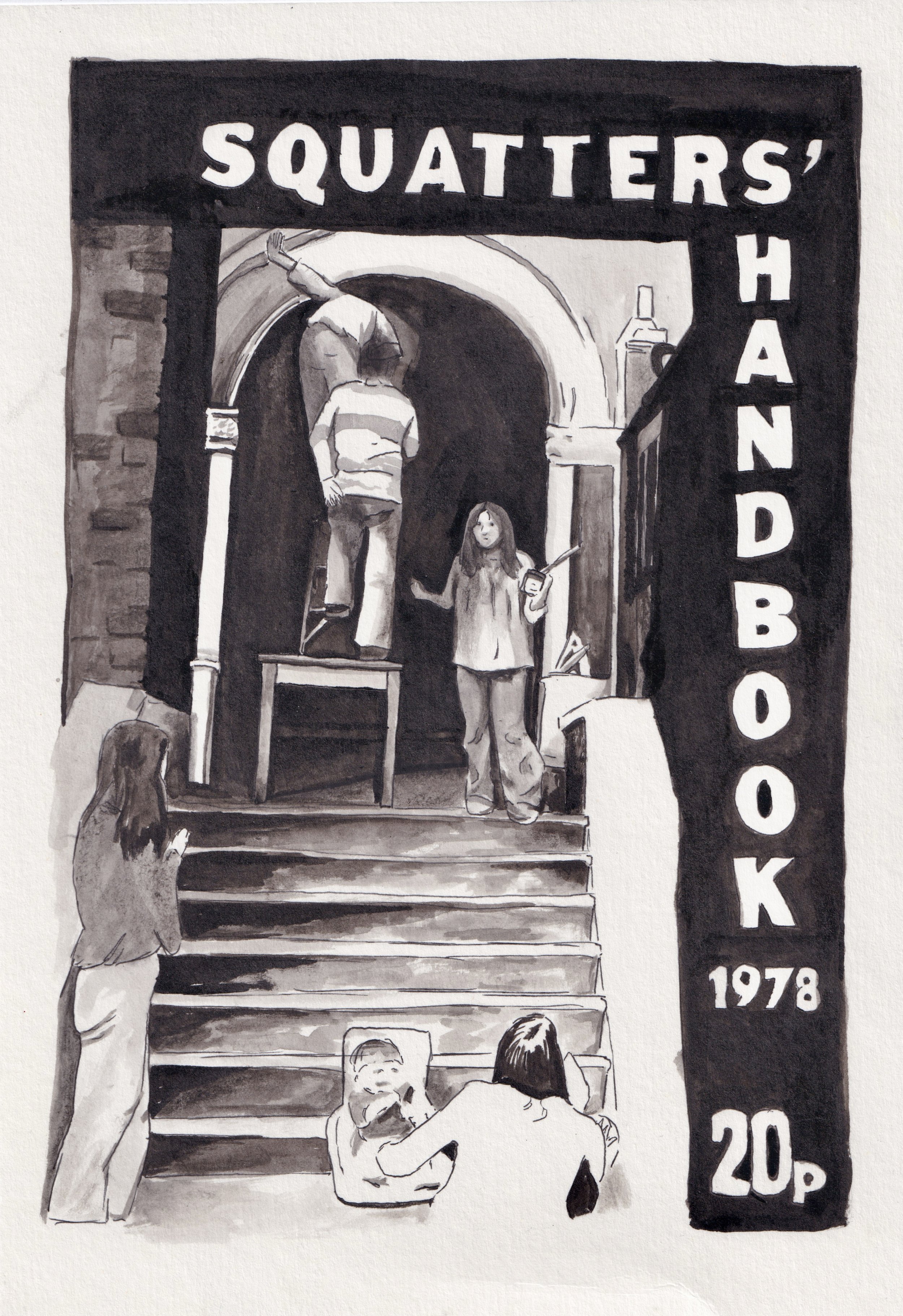

Reference image from the Squatters Handbook

Front of South London Gay Community Centre. As all of the photos were in black and white and I hadn't met Ian yet I painted the colours that I knew and did the rest in black and white.

1999 Queeruption at 121 Centre https://www.flickr.com/photos/vdjsarit/albums/72157594526445097

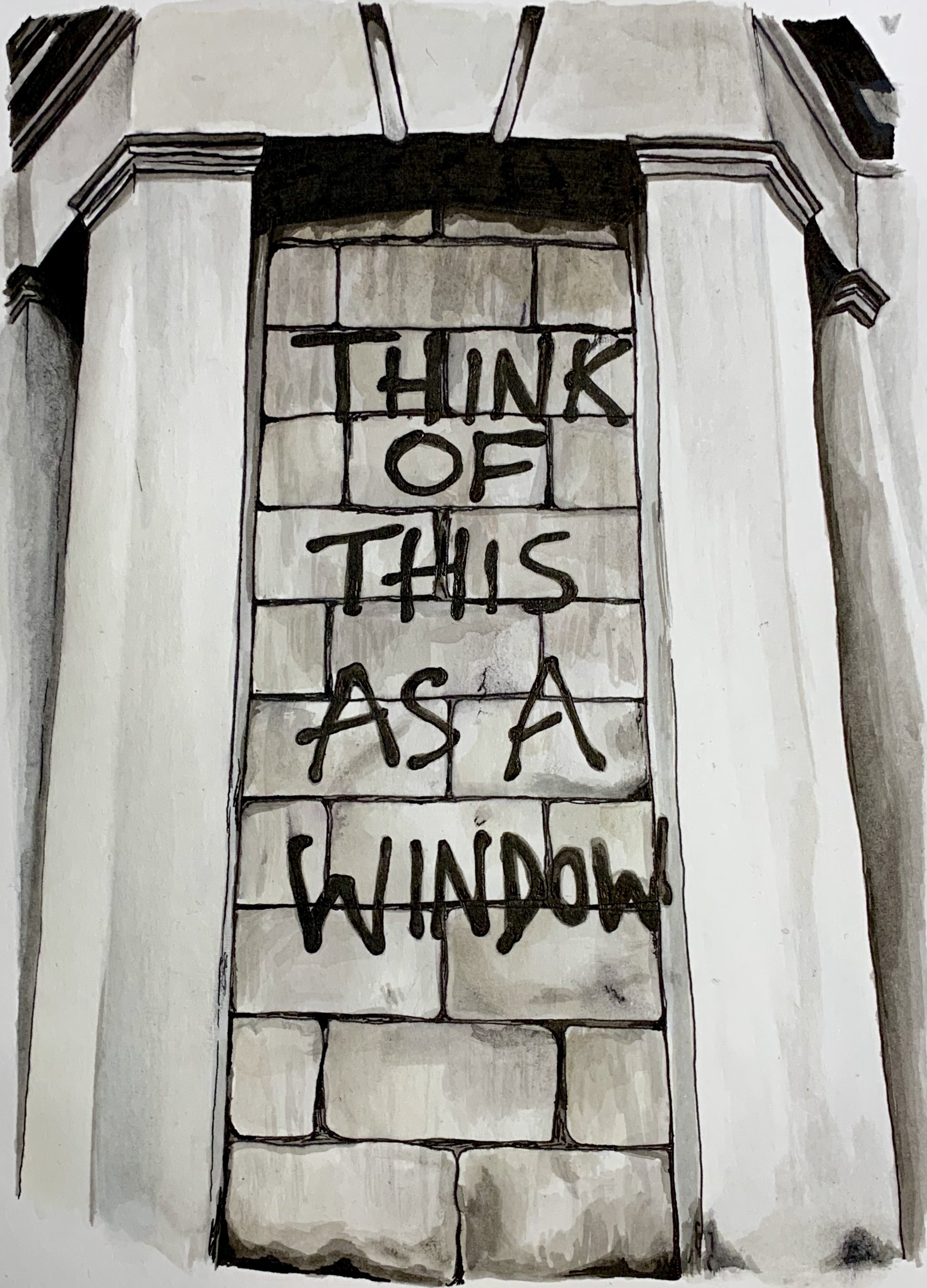

Painted from a still in Thames News Report 1982 footage. The building was obviously squatted and you could see the curtain pull back a little as someone looks out

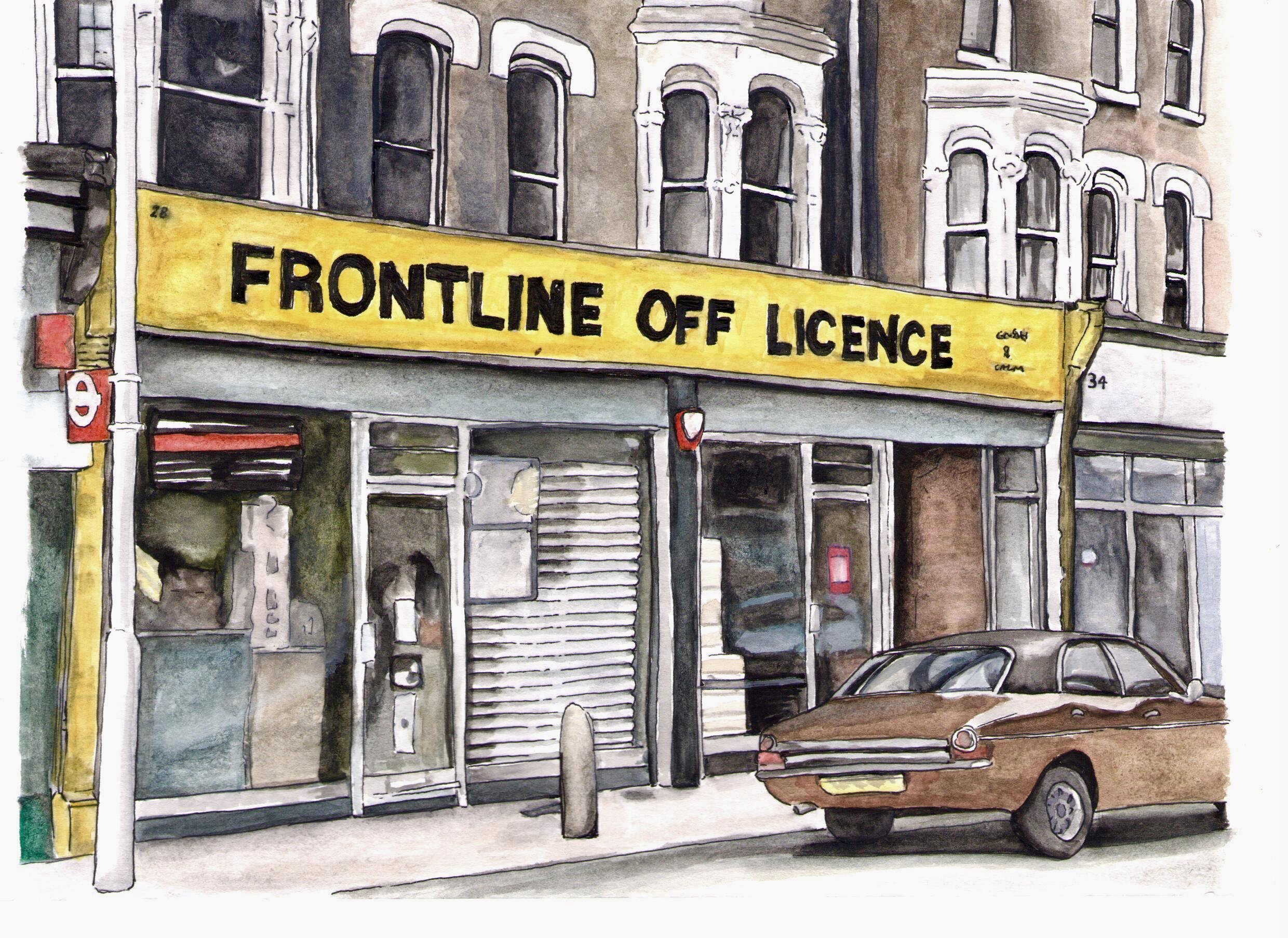

Part of Railton Road was called the 'frontline' because of it's political radicalism. Still from Thames Report 1982 footage.

Still from Thames Report 1982 footage found on youtube

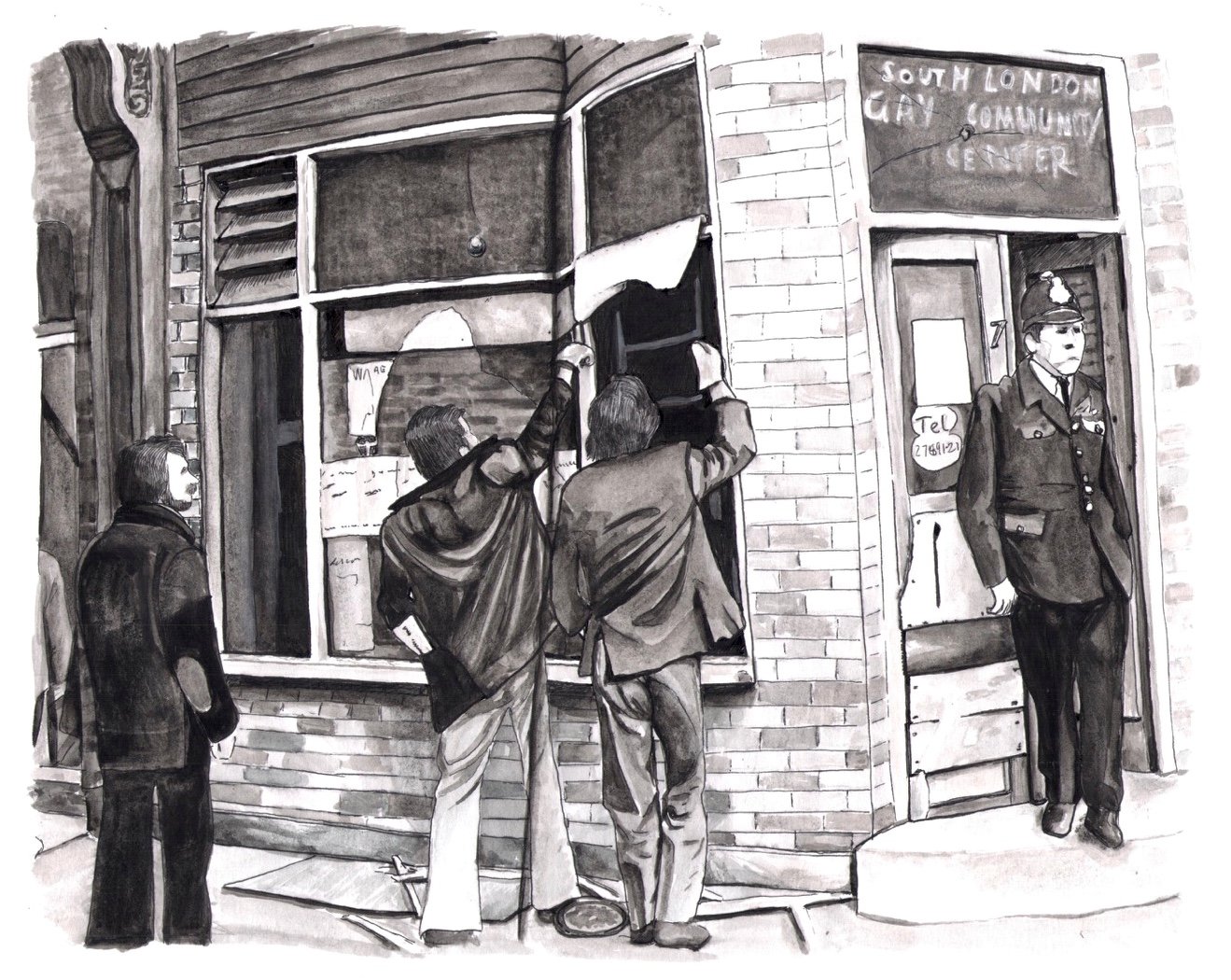

Eviction of the gay centre as seen inside the book Goodbye to London: Radical Art and Politics in the Seventies. At the time I didn't have any other way to access this image so I chose to paint the image with the creese of the book included

Unknown squatted house in South London

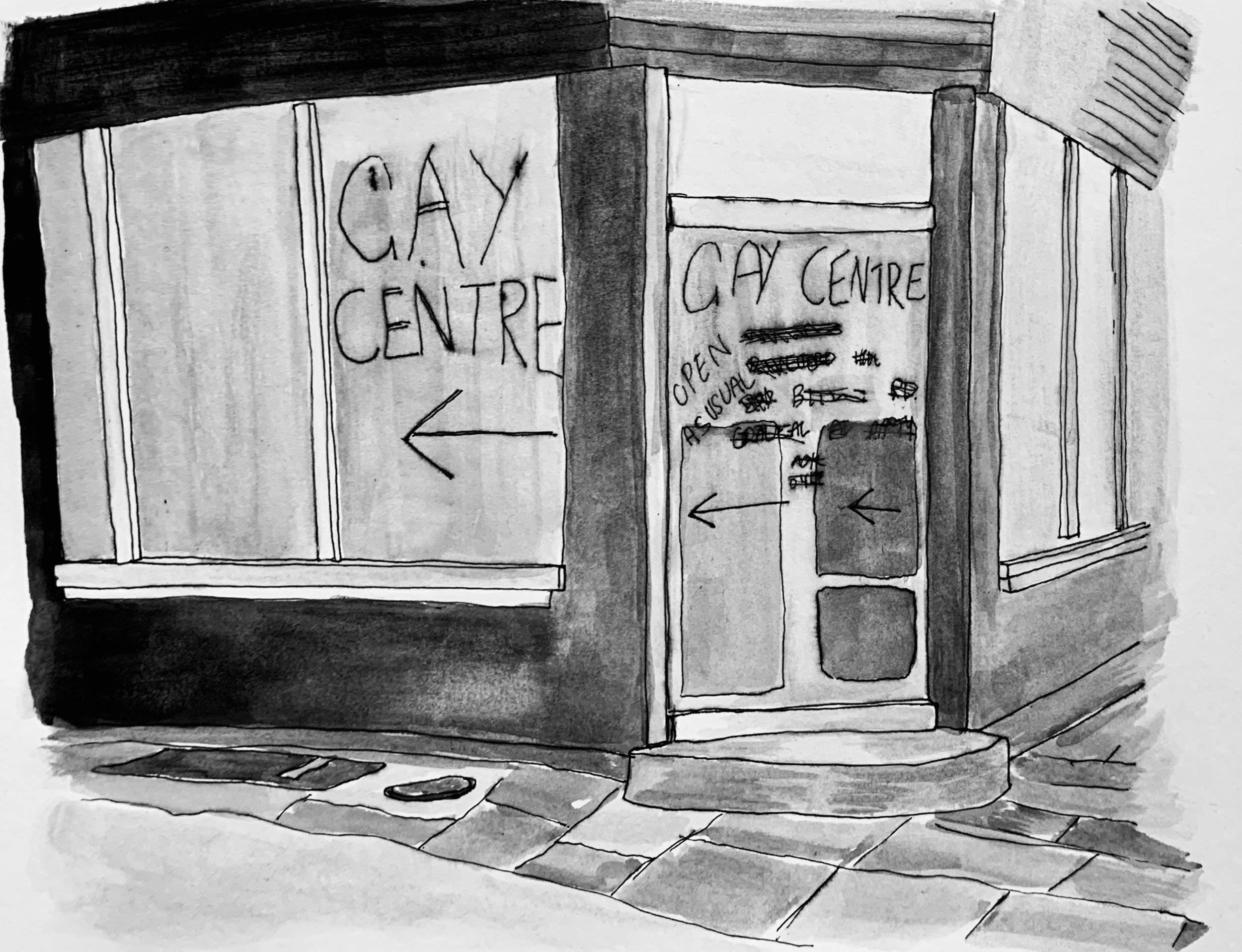

Gay Centre post eviction

Image from Squatters Handbook

1978 Squatters Handbook cover in Bishopsgate Institute Archive

Clifton Mansions evicted 2011

Atlantic Road 1982, posters on a corrugated iron fence blocking off empty lots

I could say something really insightful here about how, through developing such an emotional attachment to this very niche history, and the community of gay men who came with it, Joe was finally able to become the gay man he was always meant to be, but I honestly think that would be a bit of a stretch. (Especially as Joe isn’t actually a gay man).

Joe brought me in on this project not because of my interest in the history, but because of my special interest in website building. I had seen Joe’s fascination with the subject and took a passing interest in it. I love seeing Joe excited about things and it’s a subject closer to my heart than his collection of rare plants. Gradually though, the more I learned about this history, the more I got to know Ian, and began to recognise some of the repeating friendly faces in all these old photographs, the more anxious I became about our input into this history.

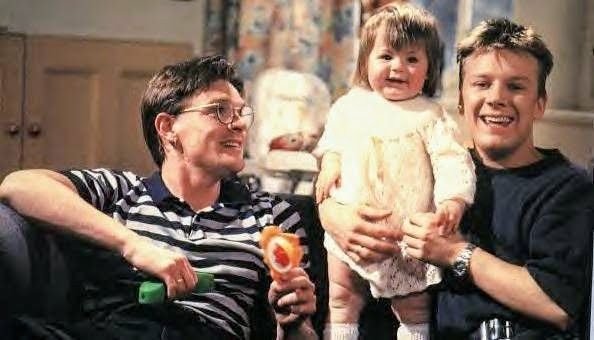

Colm in a promo photo for 'Gents'

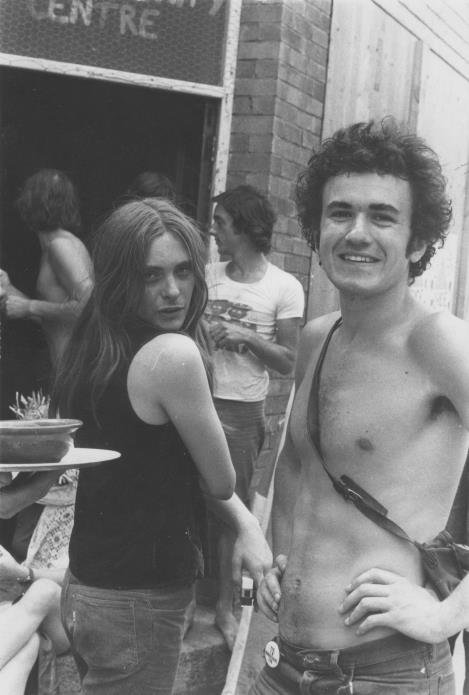

Colm shirtless outside the South London Gay Community Centre

Joe and I had watched Strip Jack Naked: Nighthawks || (1991) so Colm Clifford was the first face I was able to consistently recognise. He had such a friendly face and he’s one of the few regular members who managed to keep a reasonably consistent haircut.

Ian is also reasonably easy to spot because he’s one of the few people who wears glasses, and Joe always says you can spot Ian from the badges he’s got in places where people don’t usually put badges.

Peter Vetter (on right) at 148 Mayall Road

Tony Pitts as Emmerdale's Archie Brooks (on left). Despite what this image makes it look like, he unfortunately wasn't gay but he did (somewhat unsuccessfully) squat a building in the village

I also lately have been really gravitating towards Peter Vetter, whose descriptions of the centre really struck chord with me. “This was the first time I had been around gay people engaged in an activity other than sex which was very nice”, as an asexual person, I do find it hard to relate to some of the more sex-centred history of this community. I also think that he bares quite a resemblance to one of my favourite Emmerdale characters, Archie Brooks, so in my mind Peter has a thick northern accent (despite knowing for a fact that he was Australian).

Sometimes these people do feel like characters in a TV show, but every time I speak to Ian I am reminded that they were all real, are all real. How can we help to share everything they did and make sure to do them all justice and make young queer people take an interest in the people that fought for the rights we now enjoy and get them to see the parallels between the fight for gay rights and the fight for trans rights? These were all big concerns of mine but maybe I’m just trying to make my anxiety disorder feel useful and meaningful. I was also just anxious about the amount of admin we’d taken on.

Our community lost nearly a whole generation to AIDS, all of those memories and that knowledge is lost, and building this website feels like a chance to document what we can while we can. I’m sure that if you’ve read this far into the website, you agree that the government seriously let us down when it came to the healthcare of gay men in the 80s (unless you’re doing some extensive hate-reading!). May this is a clunky comparison that some might take offence to but I seriously think that the healthcare system for trans people in the UK right now is going to cause - or maybe already is causing - us to lose another generation of queers. Trans healthcare is suicide prevention.

Data based on GIDS’s February 2022 data, and written by Colin during June 2022

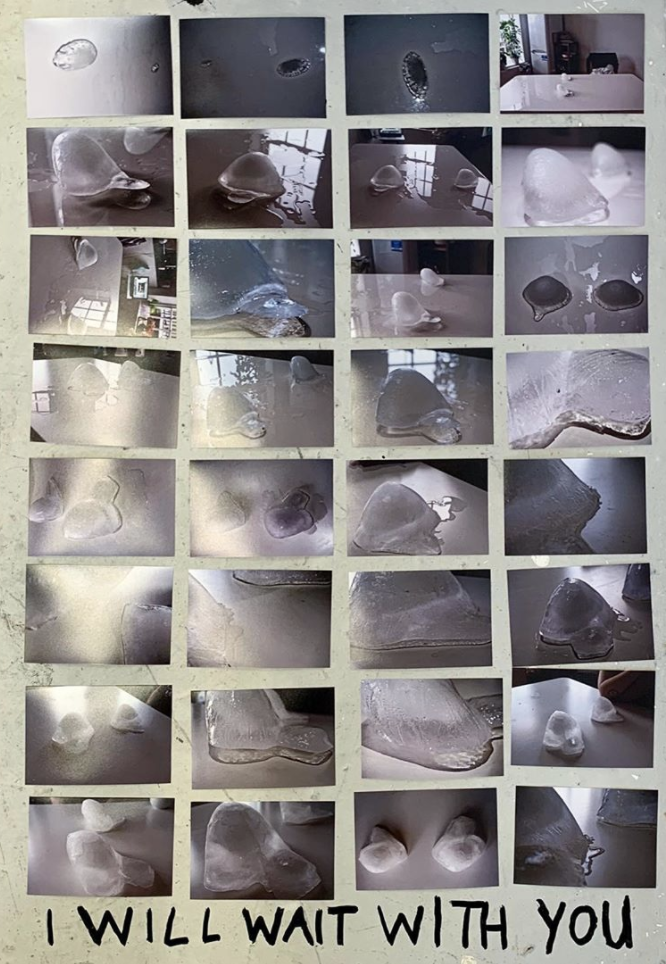

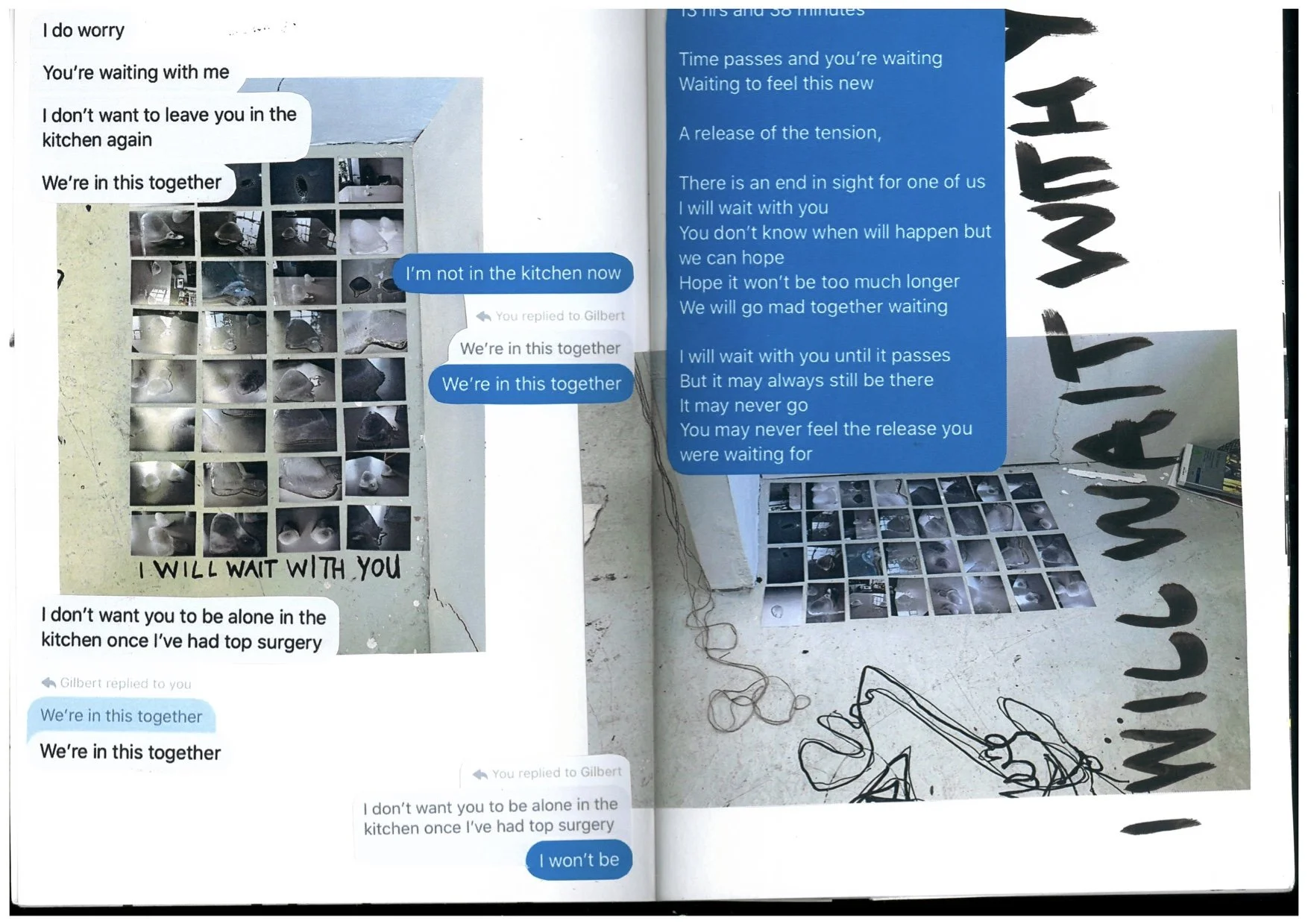

A few years ago, I think just before Joe first heard about the community of squatters in Brixton, we embarked upon a performance that ended up taking 13 hours and 38 minutes. Joe had taken a cast of my boobs and then created ice replicas of them for us to watch melt. I remember Joe warning me that it would take longer than I expected, but we ended up sat in that kitchen, waiting, waiting, waiting, until the last little bit of boob melted away at 2am. I first asked the NHS for top surgery in 2015, and didn’t get it until I managed to raise the money to pay for a private procedure in 2020.

I think Joe summed it up best in this short poem he wrote a few weeks after the performance to go alongside some of the photos he had collated:

You are waiting

We don’t know how long for

So I wait with you

It takes longer than we expect

Impatient and restless

Fed up with the situation and each other

We keep waiting

We are counting how long

And we’re waiting

It is almost over

And when it finally is

We are not relieved but more glad to finally have an end to the waiting

In the 8 years since I first came out as trans, I feel like I have done nothing but wait. For healthcare, for community, for my rights. Just as the (mostly) gay men documented on this website did, I have impatiently tried to hurry things along. We lit candles around the ice in the hopes of melting it faster, and when I felt especially desperate, in the middle of the night, I begged Joe to let me put the last flecks of ice in my mouth to get rid of them.

In an effort to speed the (metaphorical) melting up, I spent many of my teen years volunteering for an LGBT+ youth charity, and have recently started an actual paid job for them, going into schools and teaching kids that I, a trans person, am normal and friendly and deserving of rights. On the way to my first paid work at a primary school just outside Croydon, I was bombarded with adverts about whatever new things Piers Morgan and JK Rowling are doing. I can never figure out if the world is growing more or less safe for trans people. The statistics show that trans women of colour have life expectancies less than half that of their white cisgender counterparts. But how much do we really wanna talk about how shit it is to be trans?

The Oxford-based Trans Happiness Is Real project sums up my feelings on this entirely, plastering Oxford and beyond with messages of trans joy. This work doesn’t deny the shit parts of being trans, but it recentres happiness as the defining feature of the trans experience. We deserve happiness, we are capable of happiness, we experience happiness. This, for me, really echos the vibes of badges worn by queer people in the seventies, ‘glad to be gay’ being the most obvious. Queer people have always and will always be capable and deserving of happiness and glee.

Being trans is probably the best thing that ever happened to me. But I grew up in Brighton, and I’m white, and I had a very supportive parent, and I started school just after section 28 was outlawed.

Section 28 is something I keep thinking about lately, although it came into affect in the late 80s, the political climate that produced it is very easy to sense throughout a lot of the events documented on this website. Considering how many of them were unemployed, a surprisingly large number of the regular members of this group were teachers (Peter Vetter, Stephen Gee, Alastair Kerr). After becoming so invested in him and his resemblance to an Emmerdale character, I was heartbroken when I read that Peter Vetter had lost his job for answering honestly when students asked if he was gay. It’s easy for me to get frustrated feeling like I only teach about the most basic LGBT+ inclusion in my day job, I want to be having radical conversations about the nuances of gender and healthcare, but then I’m reminded that within my life time it was illegal for a teacher to “promote homosexuality”. Joe and I both work in schools and just existing as an openly queer person in that space is radical.

In my day job I spend a lot of time explaining to people that being gay and being trans are two very different things. But we are still one community, gay rights have always been fought for by plenty of people who (with the language of the present day) might have described themselves as trans, and if it weren’t for the hard work of gay rights activists, who knows where trans people would be. Trans rights are a few decades behind gay rights, but the two are inextricably linked, gay rights cannot advance without trans rights and trans rights cannot advance without gay rights. All oppression is of course interlinked, we cannot be anti-racist without assessing our fatphobia, and we can’t end fatphobia without also ending ableism, and on and on, but we aren’t two interlinked communities, we are one.

So I think what I’m getting at about Joe’s fascination with this history is that, even if he isn’t exactly a gay man, this is still his community and still his history. These are still the people who fought for his right to exist, who, like us, existed beyond the confines of hetero-cisnormativity.

Community is a significant topic that runs throughout a lot of Joe’s work. This is clear from the poem I included earlier. Despite his ADHD, Joe can be incredibly patient when it matters. It was important to him that I didn’t wait alone. It was important to him that a community is a group of people who support each other. Nothing compares to the support of people who properly get it, who feel just as I do, deep in their bones, in the very essence of their being. Even if cisgender gay men don’t have personal experience of my dysphoria, we do still have a shared history, this shared history, throughout all of us (despite what groups like the LGB Alliance want us to believe!).

Joe’s sketchbook

When I finally had my surgery date, a few days before I went under, our friends Al and Eleanor gifted me a homemade quilt. Both of them being artists working so often with textiles, many of the fabric scraps I could recognise from so many of their previous works, which were themselves often about community and queerness. When Al started taking testosterone, Joe and I added more to the quilt and gave it back to him. It has gone back and fourth between our two homes many times since then, constantly adding to it, celebrating and commiserating, giving a physical sense of the support and warmth of a good, supportive community.

'Transition Quilt' September 2020

'Transition Quilt' February 2021

'Transition Quilt' April 2022

'Transition Quilt' June 2022

When your rights are under attack, it’s important not only to fight but to make sure you also have somewhere safe and comfortable in-between the fights. Our friend Eleanor, often through the metaphor of the Cold War, regularly references the need for safe places, especially in their work ‘Inner Refuge’ (2019).

When the recent decision was made by the government not to include trans people in the conversion therapy ban, there was a protest near us in London, but in the end Joe and I decided to go swimming instead. He taught me to do a handstand in the water. Plenty of our friends and community went to the protest, but I was honestly feeling so tired and disillusioned that I couldn’t face it. This seemed like some of ‘THE WORST OF THE ATTACK’, and I wanted to stay in my ‘INNER REFUGE’. You could argue that it is a privilege to be able to bury my head but in all honesty, I think it’s a human right I should be able to use sometimes. I don’t know if I still stand by my decision not to protest that day, but sometimes it feels so tiring to just be a trans person existing in the world, that I have no idea how to muster the energy to do much more than that.

There are plenty of photos on this website of gay people protesting, but they were only capable of going out into the world, being loud and proud, because they had built themselves a safe little queer utopia in and around Railton Road to return to.

Stephen Gee in the communal garden

I use the word utopia with mixed feelings. This was the best that could be done with what little resources they had. I think Stephen Gee put it best when he said “What do you do when you open out as a social outlet where so many people have problems. Broken lives in a complete mess. How do you deal with it? That was a lot of the problem with the gay centre wasn't it. We thought it would solve itself.”.

Michael O’Dwyer diligently washing the dishes

I know that there was also plenty of bickering and fighting, but they were at least able to have these arguments with people like them, with people who wouldn’t bring homophobia into deciding who had to wash up. When I was 14 and first went to an LGBT+ youth group, it blew my mind how little we talked about it. Outside of that building I was having to figure out so much stuff and explain myself to Great Aunts, school teachers, and my mum’s horse friends. Inside that building I could play Jenga and eat biscuits and not think about it, but also not not think about it. Today I live with Joe and his partner (who is also called Joe). Every moment I spend inside of this flat I feel held, and seen, and rested. Just like in the squats, we do still bicker form time to time but at least I know that that bickering will never ever involve transphobia. The safety and community of this flat is what gives me strength to go out into the world and exist as a trans person.

When Ian suggested that Joe and I should write the last chapter of this website, we were overwhelmingly honoured. We spent months avoiding even thinking about it because we had no idea where to start. I’ve no idea if I’ve really said enough, or if I ever could say enough. I benefit every day from the work of these (mostly) gay men squatting in Brixton a few decades ago. I benefit from their commitment to community.

Further reading:

Joe’s website for more of his work (including a scale model of the South London Gay Community Centre!)

Strip Jack Naked: Nighthawks || (1991) Film available on BFI (you can get a free trail)

Colin’s website for more of their writing and other projects