The South London Gay Liberation Front stood candidates in both the local and general elections of May and October 1974

The first significant testing of the waters of a more official public presence came at the May 1974 local government elections in which Alistair Kerr, Michael Mason and Malcolm Greatbanks stood as South London Gay Liberation Front candidates for the Tulse Hill ward. Michael Mason was a staff member at Gay News and later initiated and became the editor of Capital Gay.

Besides stuffing envelopes through letter boxes on Tulse Hill housing estate the candidates addressed a local conservative association with Brenda Hancock present who stood in the October general election. Our candidates almost beat the liberals with 201 votes to their 205. They 'got into a panic' and sent one of their members to a SLGLF meeting at the Gay Centre to investigate this new political phenomenon and the possible threat to their electoral fortunes in any future general election. The intention was to recruit gay people to the Liberal cause and prevent a shaming loss of votes and relegation by the newcomers.

But it was the General Election of October 1974 that propelled Malcolm Greatbanks into the glare of publicity as parliamentary candidate for the Lambeth constituency of Norwood. He was the first and only GLF candidate to stand for Parliament making it clear that "we were putting ourselves among that group of people for whom nothing is ever done."

Having scraped together £50 towards the £150 deposit needed to stand a candidate in the election the full amount was secured by a £100 donation from Gay News. Sue Wakeling, the candidate's election agent, threw herself energetically into the campaign and took care of all the necessary measures with her 'little green handbook on election proceedings'. Being new to running an election campaign and despite her efficient organisational abilities there was a last minute panic as an insufficient number of signatures had been secured to endorse the candidate with one day left to validate his entry. Hurriedly Mary Evans Young’s signature was added without her knowledge or consent. This led to friction with the local Labour Party of which she was a member. Having been 'hauled over the coals' for supporting a candidate running against Labour Mary took her anger out on the hapless campaigners who were unaware of her political affiliations.

Using the gay centre as a base there were relays of people engaged in the mass stuffing of envelopes with election material ready to be hauled away as free publicity. There were no cavalcades of limousines or trucks or battle buses hired for electioneering purposes to boost the candidates chances of success. Frankie, the local rag-and-bone man, offered his horse and cart for use. However the trader in discarded articles did not turn up. He was recovering from a hangover from the previous night's excesses. Bill Thornycroft's van was put to good use and toured around Brixton plastered in posters and blaring out a message through a megaphone as it had five months previously in the local elections. Malcolm Greatbanks toured Brixton market on foot in a carnival atmosphere with balloons and an eager entourage of GLFers feigning television interviews with camera and microphone to boost the impression of an important and much sought after candidate. A public meeting, the only one, was held in the gay centre basement with a journalist from the Daily Telegraph turning up who self-consciously kept himself away from the main group for fear of contagion. To quote Malcolm: "He wrote up a very sneering piece in the paper the following day. Saying buggers that and buggers this and all the men carried handbags."

Bill Thornycroft's van used for electioneering in both the local and general elections of 1974

Malcolm was invited to speak on a local London radio stations, probably Capital Radio and Radio London, and was even offered a photo shoot for Vogue magazine. He turned up to the studio in hat with a leopard skin band and eye make up but nothing ever came of it. The manifesto broadcast was a garbled mess. The short time available meant he had to rush to fit in all the words.

A postman arrived at the gay centre and collected three sacks of bundled up envelopes to be delivered free of charge to the voters of the Norwood constituency and a foot-slogging, horse-and-cartless canvass was decided upon. The tall, imposing figure of Sue Wakeling, made even more gargantuan in shoes with large platform heels, contrasted sharply with Malcolm Greatbank's shortness of physical stature. With wavy red hair, drooping moustache, eye make up, head band, beaded necklace and great good humour the GLF candidate's gaudiness was even more pronounced by wearing a jacket made up of black, orange and white-striped material (described by the Times diarist as a 'blanket'). Together with a green and white shoulder bag and a lapel button proudly proclaiming GLAD TO BE GAY here was no ordinary, run-of-the-mill politician but a gaily attired novelty in the drab and broken-down environs of Brixton and bore abundant testimony to his self-description as a 'late developing hippie'.

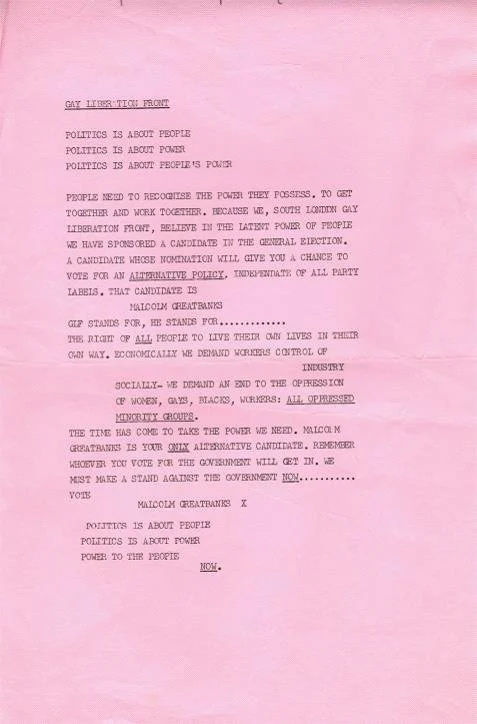

South London Gay Liberation Front election address 1974 (left) and questions fielded to candidates in the general election

There was surprisingly little hostility towards the canvassers given the previous experience of shattered gay centre windows though Sue Wakeling was almost run over by a car leading to speculation that it might have been driven by supporters of the fascist National Front. Sue pointed out how difficult it was to get out of the way quickly wearing high platform shoes. There was some misreading of who the GLF candidate was meant to represent with comic overtones. With a preference for buttonholing people on the street rather than door to door meetings some bemused people thought Malcolm was connected to the Liberal Party while others more alarmingly believed the Gay Liberation Front to be the National Front! One black voter insisted:

“You people want to send me home. I don't mind you sending me home as long as you let me come back again.“

South London Gay Liberation Front Manifesto 1974

Malcolm Greatbanks quickly reassured him that the GLF had no intentions of sending him anywhere and it was at this point the word 'Front' was dropped from 'Gay Liberation' to disassociate the group from fascism and avoid confusion.

There were serious discussions with some women on their oppression by men and Malcolm firmly registered his opposition to the nuclear family. One woman insisted that she was not oppressed but knew some of her friends who were. A fellow homosexual, who did not support gay liberation, insisted that he did not feel oppressed. He stressed the point that his homosexuality was neither a cause for shame or gay liberation militants. Malcolm canvassed people outside Brixton underground station competing with motorcades passing by of the Conservative Party and the Workers' Revolutionary Party standing a black candidate among others.

But one major issue drew storm clouds over the election campaign more than any other and caused ructions at the gay centre. Malcolm and Sue were having an affair and came across in the public domain, having been interviewed by the press, as a heterosexual couple fronting a gay liberation campaign. Gary de Vere was adamant that in the middle of running a campaign for the first openly gay candidate for Parliament with increasing media interest it was impermissible for this to continue. Gary’s argument was that the wrong message would be sent out to everyone if they were to see gay people represented by a man and a woman kissing. For him it was outrageous that the image presented to the public of a monogamous heterosexual couple should be used to represent the politics of gay liberation. Also there was very little actual political content in the interviews. To quote Gary:

"...instead of talking about gay issues and the gay campaign and gay rights and gay liberation they had been chortling with delight about how they'd fallen in love together during the campaign because they had worked closely together....planning things, writing things late into the night."

Malcolm and Sue argued that Gay Liberation was not just about one-sidedness in sexual relationships. In idealistic, utopian terms they continued to argue that it was about releasing people from all of the constraints placed upon them by straight society. They argued that a free-floating sexuality was the order of the day rather than the restrictions placed upon them of either being heterosexual or homosexual. Malcolm pointed out he also had sexual relationships with men and more prosaically insisted, regarding his sexual preferences that "They should mind their own bloody business."

This was felt by Gary to be similar to the notion held by bisexuals at the gay centre that the authentic pathway to sexual liberation was a kind of middle way and ignored the fact it is homosexuality that is oppressed for which people are imprisoned, queer-bashed, sacked, fined, and lose their jobs, friends, and families. There was always the suspicion that bisexuals could conveniently hide behind their heterosexuality and avoid the real struggle for gay liberation.

Julian How's thought that Malcolm and Sue's relationship was 'very bad tactically'. His comments on bisexuality:

"It became the rule of the day that the Gay Centre should be clearly identified as a social space for gay men and lesbians. Trans people were scarcely considered at the time and bisexuals were approved of provided they identified politically as gay and against the oppression of homosexuals and lesbians. Bisexuals, who could easily pass for 'straight', were also warned not to display heterosexual relationships at the centre that would put gay people off from attending."

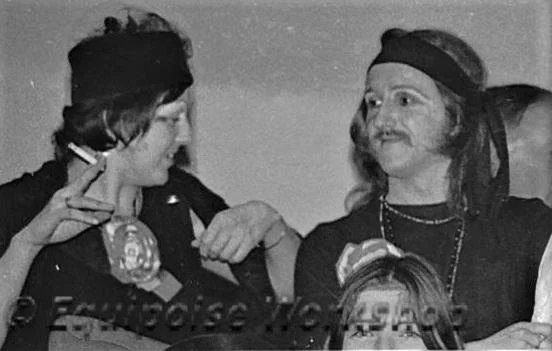

L to R: Colm Clifford (Ó Clúbhán) and Alastair Kerr at Lambeth Town Hall during the election count. Colm, while fully bearded and in drag, mischievously announced himself in the audience as Brenda Hancock, the Conservative Party Candidate. Brenda Hancock was not pleased.

Gary stormed into the gay centre one morning to confront Sue and Malcolm during an interview with the press and angrily ordered them to stop their heterosexual posturing. They both stormed out with Sue accusing Gary of male domination and bullying by dictating to her how she should should choose her own sexuality. The issue was never resolved and Gary, Alistair Kerr and Colm Clifford continued to fume and fulminate against the notion of a straight couple being the figureheads fighting on what would have been seen as an oppressed minority group unable to speak on its own behalf. This hit an especially raw nerve at a time when several inquiries from the media invited widespread publicity for the first ever open, out-loud-and-proud homosexual to stand in an election campaign. Gary de Vere was later interviewed about the candidate by a Times diary journalist after this incident who described the gay centre as a ‘shabby set of rooms in Brixton's black area in which GLF are squatting without authority‘. Malcolm had failed to turn up for the interview. Presenting images of bourgeois respectability to the media was not uppermost in Gary's mind and he was not reticent about the candidate's dissipated behaviour:

L to R: Sue Wakeling (Winter), election agent, and Malcolm Greatbanks, SLGLF candidate in the 1974 general election

"lt was terrible last night. Thirty-nine dramas. We were here all night doing envelopes. Sue threatened to resign as agent and I last saw Malcolm at 4.30 this morning, rather drunk. I should think he's sleeping off his hangover. Malcolm's great trouble has always been getting up in the morning. He was an hour late for his nomination last week."

This mocking anger and impatience with the conduct of the candidate and election agent also reflected an understanding that the general election was not to be taken seriously. Malcolm Greatbanks was simply there as a new kid on the block to promote GLF politics to a wider public and to put down a marker that we were here to stay as an out-loud-and-proud community.

The election count at Lambeth Town Hall was a hilarious hoot. What upset the smooth running of the electoral procedures was the awkward, living presence of people wearing hippie headbands, cosmetics, feather boas and glittering drag. For sheer devilment and fun, Colm Clifford, fully sporting a beard, wore a frock and a fancy hat and went about the place making outrageous statements while insisting that he was Brenda Hancock the Conservative Party candidate. This was not quite the clownish and absurd Monster Raving Loony Party the establishment had grown accustomed to. Screaming Lord Sutch had become Scruffy Squatters and Screaming Queens.

Gay News publicising Malcolm Greatbanks

The SLGLF manifesto demanded the eclectic impossible. A list of community achievements by the people of Brixton was followed by a mixture of gay liberation, marxist, socialist, libertarian, anarchist and feminist rhetoric demanding a total end to oppression by patriarchy and the ruling class through the self-organised activity of ‘people power‘. It was very much addressed to and about all the people who were marginalised and ignored by mainstream politics with gay people taking the lead in fighting for justice for all. But the actuality of gender-bending 'screamers' sharing a stage at Lambeth Town Hall with more respectable, besuited candidates caused some turbulence. The expectation was that it would all end in tears with polite but firm requests for the supporters, if not the candidate, to leave the premises forthwith.

Gary de Vere is clear about how the usually competing political parties became united in their opposition and hostility towards the Gay Liberationists:

"The agent for the Labour Party....said to me "You have set your cause back twenty years tonight" and how we laughed and said "You really mean it's going to take you twenty years to get over this?" They said "you're making a mockery out of Parliamentary politics" and we said: "YES!”.

He was also clear that events like this were good for people who were there but lacked the courage and confidence to be upfront about being gay: "With them being present....they could see that you could be as cheeky as you like and.....survive and come home laughing."

Camping it up and irreverently lampooning the election count confirms Julian Hows comment on LGBT+ protest generally:

"One of the peculiarly English things that we are actually quite good at, especially in gay politics, is that we make fun of things! And making fun of authority sometimes changes more things than balaclavas and Molotov cocktails, and it’s another form of peaceful demonstration."

Though it has to be pointed out that some of the SLGLF election count attendees were, in fact, Australian and Irish.

The SLGLF got 223 votes (beating the Liberal Party) which counted for 0.7% of valid votes counted which scarcely mattered given publicity was the main aim of the campaign as an untried and untested political entity.

The election had very little to do with the full-blooded revolutionary ideals and politics of the original Gay Liberation movement. There was a muted attack on patriarchy, capitalism, heterosexism and male power. The general approach was, of course, not to give a damn about the electoral process or the 'sham' of parliamentary democracy. Malcolm Greatbank’s gained less than 5% of the valid votes cast and as fully expected lost his deposit. Even so the SLGLF played the game.

In recognition of the lacklustre approach of the other parties the campaign was deliberately started late to exploit the boredom of the people of Brixton with other candidates thus allowing a greater opportunity to create interest in the SLGLF candidate. The whole point of the exercise was to obtain high-profile visibility and to put our politics across to the public. The best that was achieved was the creation of a little colourful life to the streets of Brixton in an attempt to punch a marginal hole in the dullness of a society embedded in a greying, decaying culture shaped by capitalist dereliction. Prejudice and bigotry had been challenged through an unashamedly militant display of radical Queendom. Above all it was performed in a playful, camped up, carnival atmosphere bringing colour and fun against the dampening rigidities of a dour and grey conformity to traditions that disallowed inventiveness, experimentation and innovation.

*paraphrasing the hippie peace and love cry: 'We are the people our parents warned us against".

Sources

The Times Diary, 1974. Account of 'Gay Libs' election candidate

South London Press, 9/4/74. 'Gay Liberation candidates will contest election' (local election)

South London Press, 30/4/74. 'Candidate for local election in Tulse Hill ward'

South London Press, September 1974. 'Gay Movement will have a candidate' (general election)